White House Tariff Announcement: Initial Reaction

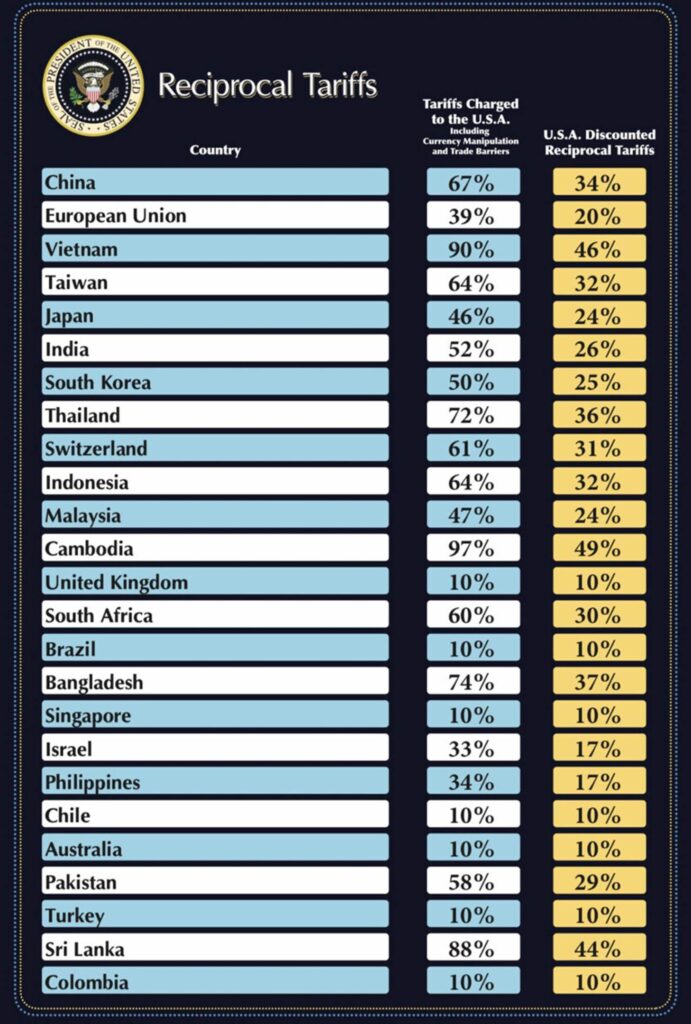

Yesterday, President Trump announced a broad array of tariffs in what is arguably the most consequential trade action since the establishment of the WTO in 1995. Invoking national security interests, the President announced the imposition of a 10% minimum global tariff effective April 5th. Canada and Mexico were the only notable exceptions, with USMCA-compliant goods continuing to be exempt from tariffs. The President also announced that reciprocal tariffs above and beyond this 10% level would be applied to numerous countries beginning on April 9th. Of note, this includes a 20% tariff rate on imports from the EU, a 34% tariff rate on China, a 46% rate on Vietnam, and a 24% rate on Japan.

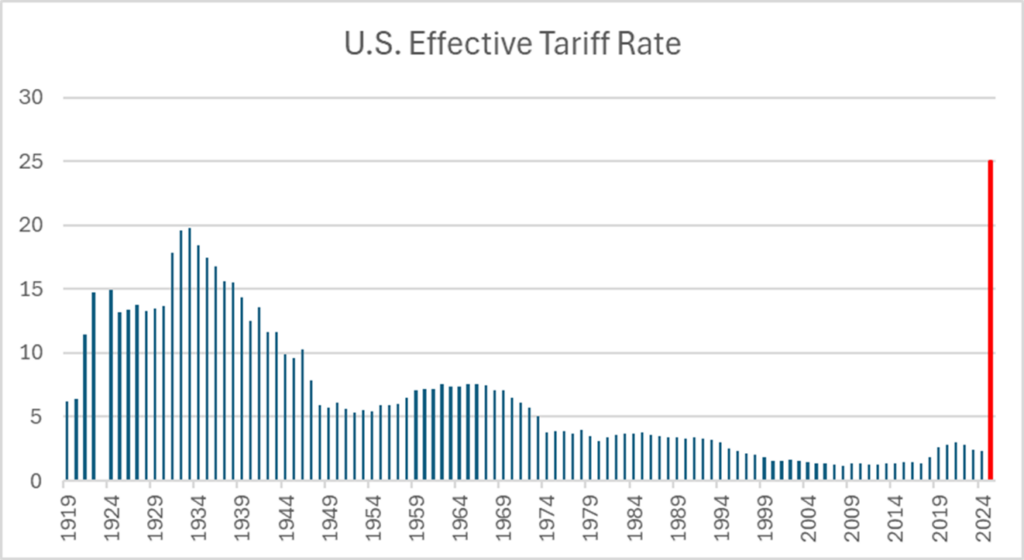

These actions constitute a seismic shift in the global trade order. Estimates vary on the exact numbers, but a rough consensus amongst economists is that this will take the effective tariff rate from its current level of ~2% to somewhere in the 25-35% range, the highest level since the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930. In the century since, tariff rates gradually declined with the establishment of broad multilateral trade agreements and organizations (such as the WTO) created to enforce trade rules. At a minimum, the President’s actions mark a stark reversal in that trend, which may be difficult to unwind going forward.

The situation is still largely in flux. It remains to be seen how durable the announced tariff levels are, or in some cases, what the actual level will be. For instance, in its official chart the White House reported a tariff rate of 34% on China, but subsequent reporting by Eamonn Javers of CNBC suggests that this may apply on top of the existing 20% tariff on China, resulting in a cumulative tariff rate of 54%. There is little clarity regarding how overlapping tariffs on products and geographic jurisdictions will interact with one another.

That being said, the macro implications of these actions are difficult to ignore. Assuming no change in trade volumes, a 20% increase in the effective tariff rate would correspond to ~$660B in new tariffs. For reference, this would equate to the largest tax hike in over 50 years and 13% of the entire federal revenue base of ~$5T annually.

Actual tariffs collected would likely be well below this as trade volumes decline and the exchange rate swings. Invariably, a portion of the tariffs will flow through to consumer prices. In his initial take, JP Morgan Chief US Economist Michael Feroli estimated that the announced measures could boost PCE inflation by 100-150 basis points this year. According to Feroli, the resulting hit to purchasing power “could take disposable personal income growth in 2Q-3Q into negative territory, and with it the risk that real consumer spending could also contract in those quarters. This impact alone could take the economy perilously close to slipping into recession.” Add on top of this a potential reduction in trade volumes and lower private investment via uncertainty channels, and the outlook for growth looks murky at best.

Source: Donald Trump via Truth Social

Source: U.S. International Trade Commission, Bloomberg

Fed:

The implication of both higher prices and lower growth from tariffs doesn’t provide a clear directional signal for Fed policy. It’s perhaps for this reason that Fed futures did not move significantly following the announcement, with the market still projecting a relatively low (25%) probability of a cut at its next meeting in May. The market now projects four cuts in 2025, up from three, with the first coming in the June meeting.

Markets:

Markets were caught off guard by the magnitude of the announced tariffs. Equities experienced a large sell-off, with the S&P falling by 3% and the Nasdaq declining by 4% at the open. Bond markets rallied, with the 2-year Treasury rate falling 14 basis points to 3.72% and the 10-year declining 11 basis points to 4.02% (as of 10am this morning). Inflation breakevens were generally unchanged, meaning that the decline in Treasury yields was linked to lower real interest rates. Collectively, this suggests that the market views the negative impacts of tariffs to be more meaningful for growth than for inflation. This is in line with textbook theory that trade restrictions result in a one-time uptick in the price level rather than persistently higher inflation.

Credit:

It will likely take time for the downstream effects on individual companies to manifest themselves. U.S. companies enter this period from a position of relative strength, with private sector leverage relatively low and earnings growth generally strong. This suggests that they may have some buffer to absorb volatility without experiencing ratings downgrades in the near term.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.