The Paradox of the Present-Day ESG Investor

Cash investors looking to incorporate ESG face an interesting dilemma: Can you invest in oil majors while claiming to be an ESG investor? The answer may surprise you.

Part 1: A Recent History of Energy

The prominence of ESG investing has increased significantly in recent years, and nowhere has its impact been felt more than by oil and gas producers. The looming threat of climate change has driven activists to pressure oil and gas producers to move towards producing more renewable energy to meet the ambitious goals set by the Paris Agreement in 2015: reduce carbon emissions by 45% by 2030 and reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

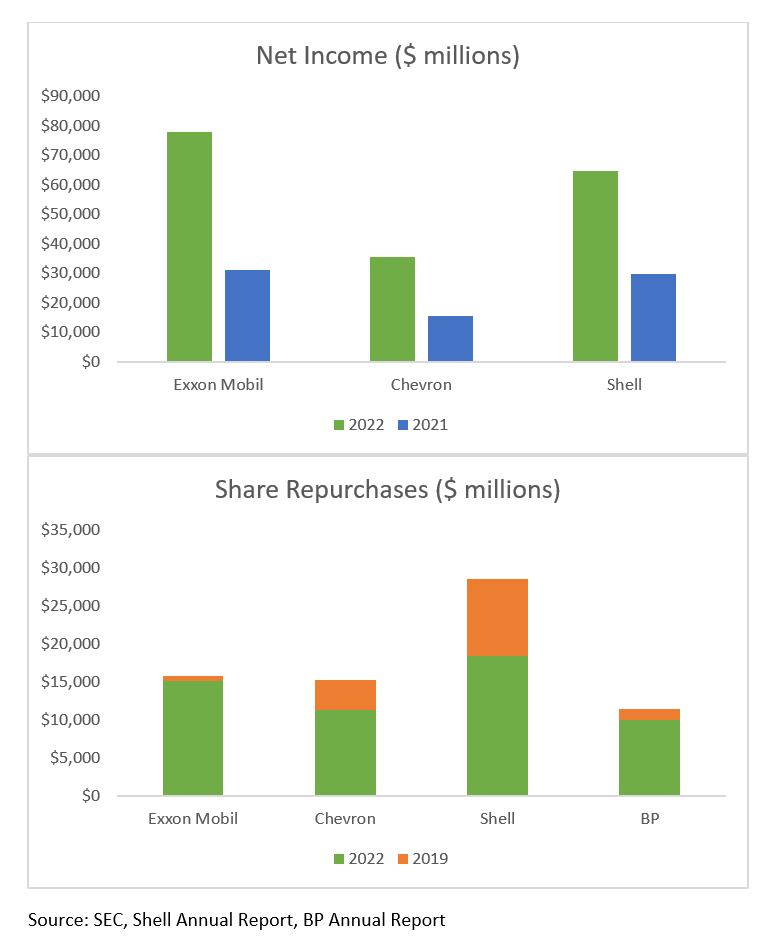

To that aim, in 2021, a Dutch court ruled that Shell must reduce emissions from their previous 2019 levels to the targets specified by the Paris Agreement. That same year, the activist firm, Engine No. 1, gained three seats on Exxon Mobil’s board with the support of major institutional investors Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street by promising to push for more aggressive emissions cuts. Both outcomes were consistent with a broader social movement to accelerate energy companies’ adaptation of more environmentally sustainable business models. These efforts lost some momentum following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which sent oil and gas prices soaring. The result was unprecedented profits for energy majors, which translated into sizable shareholder returns. Collectively, Exxon Mobil, Chevron, and Shell earned $178.2B in 2022, more than double the $76.7B reported the year before, despite impairments to Russian assets. At the same time, high global inflation led governments, who once demanded emission cuts, to call for increases in oil and gas output to alleviate inflationary pressure. Following a year of energy instability, a new narrative rose to prominence: The energy transition must not be rushed, or consumers will suffer.

Exhibits 1 and 2: Net Income and Share Repurchases of Exxon Mobil, Chevron, and Shell

Part 2: The State of Energy

Following this shift, some integrated energy companies have begun to wind back their ambitious plans. In 2019, BP announced plans to cut both oil output and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 40% from 2019 levels. Last February, they scaled back their plans and revised their GHG reduction target to 20-30% and their oil output reduction target to 20%, half the initial target. Similarly, in mid-June, Shell quietly eliminated language referring to 1-2% annual cuts to oil output by 2030, claiming they had met their goal through asset sales.

Shareholders have also been quieter regarding the energy transition, with emissions-related shareholder resolutions facing weaker support than two years ago and little progress from Engine No. 1. For now, Wall Street seems to be accepting of a slower energy transition.

One could argue that the energy companies are prioritizing shareholder returns over decarbonization, but the reality is more nuanced. Consider, for example, the transition towards electric vehicles. While the European Union and various state governments in the US have put forward plans to rapidly accelerate the shift to electric vehicles, the power grid cannot handle a dramatic shift due to bottlenecks bringing charging devices to individual homes. Furthermore, manufacturing of electric vehicles isn’t completely green, as oil and other carbon-intensive fuels are required to produce electric vehicles as well as power the grids that charge them. Moreover, EVs require an even greater concentration of rare-earth metals than traditional gas-powered vehicles, extraction of which has various social risks such as bribery, corruption, and human rights violations. Bottom line, the path to net-zero—or ESG investing for that matter—is not always clear-cut. Near-term, oil and gas companies are required to avoid energy shortfalls and mitigate price volatility.

Part 3: The Paradox of ESG and Fossil Fuel Investment

Energy companies have adapted to changing trends and have invested in businesses and technologies which aim to reduce emissions and meet the need for the energy transition. While wind and solar are popular renewable energy sources, energy majors have placed greater focus on fuels more in-line with their current experience. This includes existing fossil fuels with relatively lower carbon emissions compared to oil and coal, such as natural gas, biofuels, and hydrogen. It also involves development of new technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CC&S), which involves capturing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it underground. Successfully increasing the scale of these fuels and technologies to meet energy targets and adapt to a renewable future while managing profitability is critical to the viability of these companies.

Herein lies the paradox of the ESG investor: While energy companies have a very large carbon footprint, they also are in the business of moving the world into a net-zero future. In addition to expertise, these companies also have substantial profitability to fund research and investment into renewable and low-carbon technologies, making their financial condition far more sound than many pure-play renewables competitors. While many demonize the business of fossil fuel companies, an orderly transition likely cannot be completed without them.

Concerns for Cash Investors

There are two major risks for cash investors. More ESG-focused investors may face challenges in tracking the sustainability strategies of energy companies, as it can be difficult to get a clear picture of how operations affect profitability and emissions. For example, emissions could be reduced in the near-term due to heavy reliance on “stopgap” fuels like natural gas but lack the mix of renewable and low-carbon products to meet longer-term goals. Additionally, many companies bundle their renewable businesses with other businesses, making it difficult to see how they impact earnings. Finally, the renewable and low-carbon businesses are much smaller than legacy oil and gas businesses, which may detract investors seeking investment vehicles with a greater environmental impact. All of this may deter more ESG-focused investors.

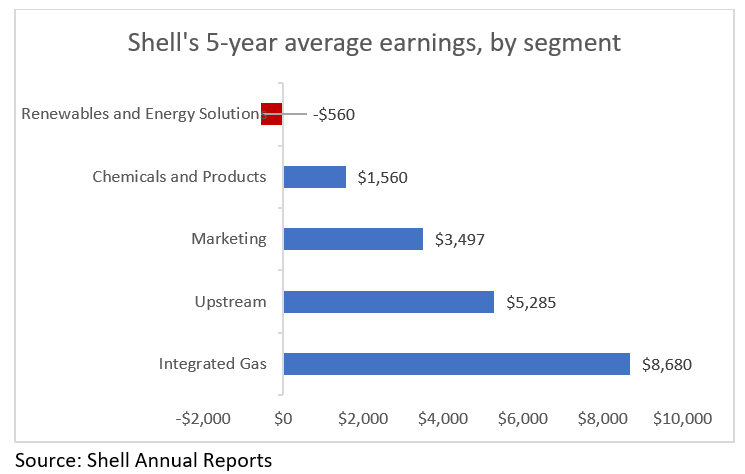

From a more traditional focus, low carbon businesses at present are less profitable than legacy operations. While oil and gas typically produce internal rates of return ranging from 10-20%, BP expects renewable energy returns of only 6-8% and roughly 15% for biofuels. As a result of the lower IRRs, low carbon businesses tend to struggle with profitability and may exhibit losses, as evidenced by Shell’s financial results. Because of this, management and shareholders of many integrated energy companies have been reluctant to increase the speed of the energy transition.

This lack of investment, in turn, creates its own set of problems. The threat of significant regulation near-term is muted, as energy price instability is fresh in the mind of the consumer (and voter). However, longer-term, these companies leave themselves exposed to changes in public opinion and regulation should they fail to adequately evolve their business models. In short, management faces a major challenge of balancing short-term profitability with long-term threats to the existing business, a source of significant credit risk.

Exhibit 3: Shell PLC’s 5-year average earnings, by segment.

Conclusion

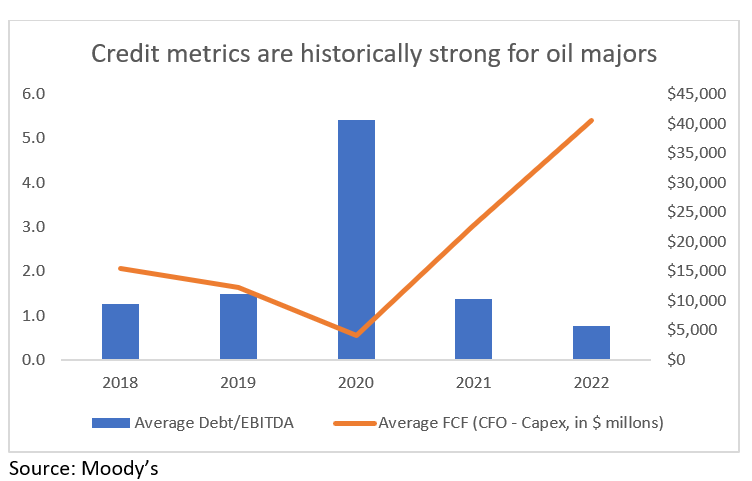

Taking all this into account, should cash investors avoid investment in energy companies given the ESG risks? The answer depends on how much ESG factors into investment decisions. While long-term risks remain, at present energy companies hold very strong balance sheets due to high returns in 2022, making their debt appealing vehicles to park cash. Although credit metrics will likely be relatively weaker going forward due to lower commodity prices, downside risks to global growth, and possible M&A activity, these names have the fortitude to withstand short-term volatility, particularly when considering a long history of strong governance.

Exhibit 4: Average debt/EBITDA and free cash flow for 5 largest oil majors (Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, Total Energies

For a cash investor focused on ESG integration, where ESG is one of many factors in the decision-making process, energy companies may be appropriate for cash portfolios. The near-term risks to credit ratings related to the energy transition may be low, but investors should be aware of the long-term risks to existing operations and the uncertainty surrounding implementation and financial impact. Analysis of environmental and social factors suggests these companies have the potential to operate successfully in a net-zero world, but insufficient governance with too much focus on short-term oil gains could negatively impact credit profiles. For an investor with a greater emphasis on ESG, energy credits may not align with their goals given the high level of emissions, due to the carbon-intensive nature of operations, and relatively small scale of low-carbon businesses versus oil and gas operations.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.