The New Money Fund Reality

Abstract

The 2014 money market fund reform brought forth drastic change to the corporate cash management landscape, significantly impacting investors, issuers and fund sponsors. While there is little doubt that money market funds are more resilient following the implementation of the reform’s higher credit, liquidity, transparency, and oversight standards, it also had some unanticipated side-effects. Changes in the utility of MMFs, particularly prime funds, and concurrent changes in investor perceptions of these instruments, led to a large-scale migration in assets from prime to government funds. Resulting changes in the demand dynamics of the short-term debt markets may have had unintended consequences for fund manager incentives. Three years after the reform’s implementation, we believe it is worthwhile to evaluate the reform’s regulatory outcomes against the backdrop of its original intentions. Following the recent completion of the European Union’s MMF reform, the opportunity to compare and contrast differences in outcomes can also add value to the discussion—especially given the two regulators’ differing approaches. While there is strong evidence that the reform hit close to its mark, we note that there may still be room for improvement.

Introduction

Money market funds, since their inception, have provided investors with a deposit-like option for parking idle cash. Through careful risk management and the use of book value accounting, they aimed to offer a dollar-in dollar-out utility to investors at market rates. But the financial crisis of 2008 and the collapse of Lehman Brothers demonstrated that this model was unsustainable. Investor panic following the Reserve Primary Fund ‘breaking the buck’ led to collective runs on prime money market funds (MMFs) which disrupted the short-term funding markets and risked impacting the rest of the financial system. The severity of the shock necessitated government intervention to contain the panic and return short-term markets to operation. This experience spurred calls for regulatory reform to fortify the MMF industry.

The SEC enacted its first round of reforms in 2010, where it pushed MMFs to increase transparency, reduce the average maturity of their holdings and boost liquidity. While this improved the risk profile of prime MMF portfolios, the European sovereign debt crisis that soon followed showed that significant run risk was still present. US MMFs with European bank exposures experienced substantial outflows, which in turn impacted short-term funding conditions. This indicated that the recently implemented reforms had missed their mark.

In 2014, the SEC announced changes to the original 2010 reforms that went on to more radically change the face of the MMF industry. Notably, in seeking to reduce run incentives for investors during periods of stress, this reform changed the deposit-like nature of prime and municipal MMFs by introducing a variable NAV (net asset value) and the possibility of redemption limitations should certain liquidity barriers be breached. In this paper, we examine how the new 2a-7 reform has impacted the money market landscape, focusing on prime MMFs which were most heavily affected. We review recent literature and evaluate the extent to which the reform has been successful in meeting regulators’ goals of safer portfolios with a lower probability of runs. We then briefly compare and contrast the outcomes of the US MMF reform with those of its European counterpart and conclude with a look at current challenges facing cash investors.

Changes in Prime MMF Utility

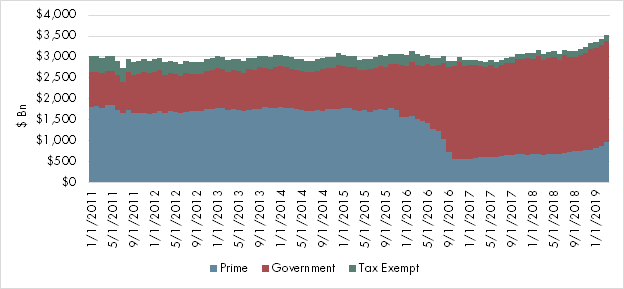

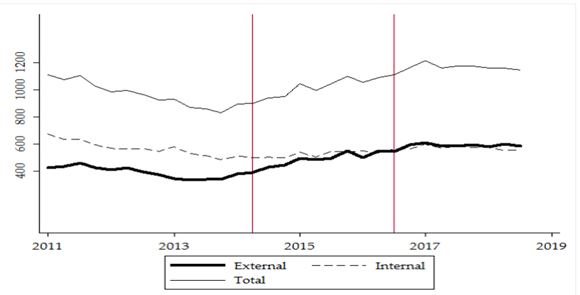

The 2014 MMF reform resulted in a radical change in the nature of prime MMF liabilities. In looking to improve the resilience of the MMF industry, the deposit-like utility of prime MMFs, a mainstay for cash managers, was significantly impaired as investors could now be exposed to market fluctuations and potential redemption limitations. This decrease in prime MMF ‘moneyness’1 was the driver of a mass investor migration that saw approximately $1 trillion in assets move from prime to government funds (Figure 1).

Figure 1: US MMF Assets

Source: The Office of Financial Research

The introduction of a variable NAV changed the character of prime MMFs shares from a debt-like instrument to a more equity-like one, as well as from a safe asset to a slightly riskier one. Research suggests that this change in the nature of prime MMF liabilities may have, in turn, impacted portfolio managers’ investment incentives. Baghai, Gianetti and Jäger (2019) propose that investors will tend to monitor their investments more once the payoffs of their claims stop being debt-like and are more sensitive to the value of their underlying assets. These greater monitoring incentives may have lent more prominence to risk adjusted return as an investment criterion, altering investors’ perception of prime MMFs to being more in line with that of bond funds.

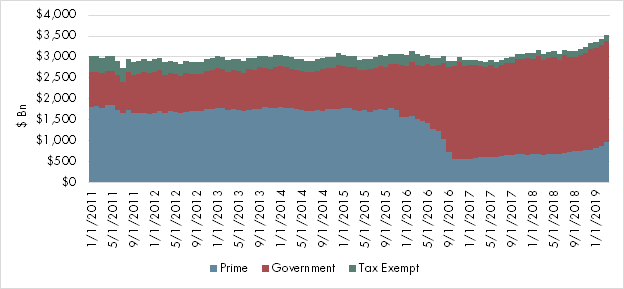

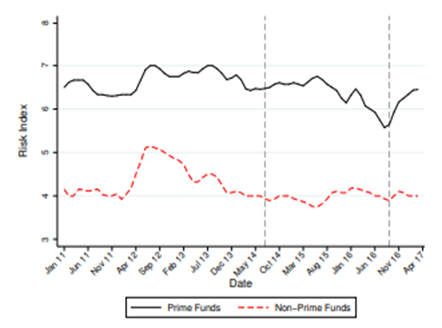

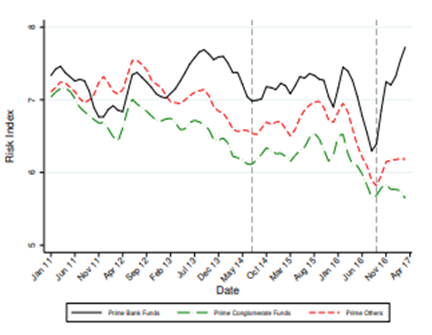

This added focus on returns creates a higher sensitivity of flows to performance, which given the compensation structure of MMFs, a flat fee levied on AUM, may incentivize fund managers to take on more credit risk (Figure 2). As a result of the newly implemented liquidity requirements, managers are limited in their ability to capture value further out on the curve, leaving credit as the main lever for managing portfolio returns. This effect is more pronounced for institutional funds, perhaps as a result of the greater capacity of institutional investors to monitor fund performance (Figure 3).

Figure 2: MMF Risk Index Scores by Fund Type

Source: University of Colorado Boulder, Shadow Banking Concerns: The Case of Money Market Funds, Alnahedh and Baghat, 2017

Figure 3: Prime MMF Risk Index Scores by Sponsor Type

Source: University of Colorado Boulder, Shadow Banking Concerns: The Case of Money Market Funds, Alnahedh and Baghat, 2017

The authors of this study used a combination of credit indicators such as CDS spreads, WALs, credit ratings, unsecured holdings and opaque security holdings to construct a credit risk index for MMF portfolios. As expected, prime funds carry more credit risk than their non-prime counterparts. Notably however, their risk index score spikes after the reform’s implementation date. Large, bank-sponsored funds score the highest on the risk index. This may be due to synergies that banks are able to achieve by using affiliated funds as a means of attracting deposits and supplementing fee income. In turn, this could incentivize bank sponsored funds to manage portfolios more aggressively in order to retain or attract prime investors.

In a way, the 2016 MMF reform segregated prime MMF investors into risk cohorts, with the most risk-tolerant investors remaining within the prime category. There is some question as to why the more conservative funds didn’t attempt to emulate a constant NAV through greater liquidity and higher portfolio credit quality. Instead, following the implementation of the reform, a relatively high proportion of them chose to convert from prime to government. A likely reason for this, according to Holmström and Tirole (2011), is that while a VNAV fund may try to maximize NAV stability, that may not be enough to convince investors that fund liabilities carry no variability or redemption risk in the absence of regulatory or government guarantees.

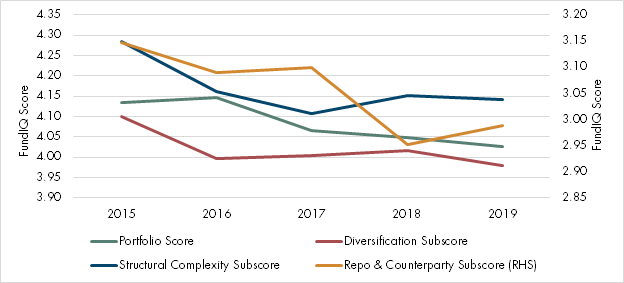

This increase in prime MMF portfolio risk appears to be corroborated by Capital Advisors Group’s FundIQ® data. Figure 4 shows the annual peer group averages for FundIQ’s Portfolio Score and Subscores. A lower score indicates a worse performance in the related category. Each subscore represents an evaluation of pertinent characteristics derived directly from fund holdings and/or fund data aggregators’2 statistics.

Figure 4: Capital Advisors Group FundIQ® Model

Source: Capital Advisors Group

While the MMF industry should be more resilient when confronted with the run-like behavior that called for government intervention in the past, higher portfolio credit risk increases a fund’s sensitivity to a turn in the business cycle. This could be problematic for prime investors given that variable NAV makes them vulnerable to market fluctuations. Moreover, with large systemic bank sponsors managing the riskier strategies, there is a possibility of contagion to the rest of the financial system if fund portfolio losses require large capital infusions from their bank sponsors.

Impacts on the Short-Term Funding Markets

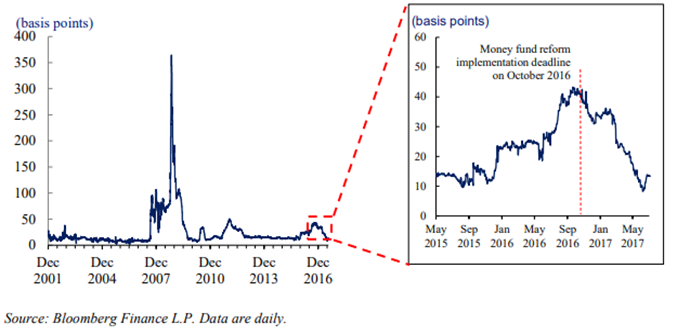

Prime funds have long served as a reliable source of short-term funding for corporations. The large asset migration from prime to government during the implementation period of the MMF reform presented a funding challenge for short-term borrowers, as demand shifted from the private sector to government and government-sponsored issuers. Market participants expressed concerns over potential spikes in funding costs from short-term volatility, as well as longer-term funding availability due to the structural change in the market. As can be seen in Figure 5, however, these concerns were somewhat overblown.

Figure 5: Three-month LIBOR-OIS Spread

Source: Office of Financial Research, The Intersection of U.S. Money Market Mutual Fund Reforms, Bank Liquidity Requirements, and the Federal Home Loan Bank System, October, 31, 2017

LIBOR-OIS spreads, a measure of bank funding conditions that excludes the impact of changes in the federal funds rate, show that funding costs returned to normal levels shortly after the reform’s implementation date despite the fall in demand for prime assets. This was in part due to increasing utilization of Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) advances by large U.S. banks as an alternative source of funding.

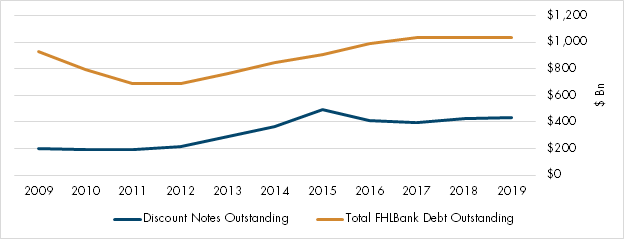

The Federal Home Loan Bank system was established in 1932 to support mortgage lending by offering collateralized loans, usually by mortgages, to member banks. These loans, termed advances, are available in various maturities and can carry fixed or variable interest. The FHLB banks, in turn, fund their operations through issuing debt obligations in the open market. Because the FHLB is a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE), its debt can be purchased by government money market funds. In this way, member financial institutions can indirectly raise short term funding through the money markets. Figure 6 shows the growth in government MMF holdings of FHLB securities following the implementation of the MMF reform in October 2016.

Figure 6: Gov’t MMFs Increase Purchases of FHLB Debt

Source: FHLBanks Office of Finance

The increased reliance on government MMF demand for FHLB securities creates a link between bank funding conditions and the acceptance of FHLB debt by fund managers. Importantly, the vast majority of advances from the FHLB system are borrowed by the 10 largest U.S. banks3 who also use FHLB advances to meet their LCR (liquidity coverage ratio) requirements4. This creates potential systemic risks in the event of a funding shock for the FHLB System. Uncertainty over the implicit government guarantee on FHLB debt or concerns over the system’s asset quality, capitalization, or liquidity could spill over to the broader financial system. It should be noted, however, that the probability of such events materializing is rather low.

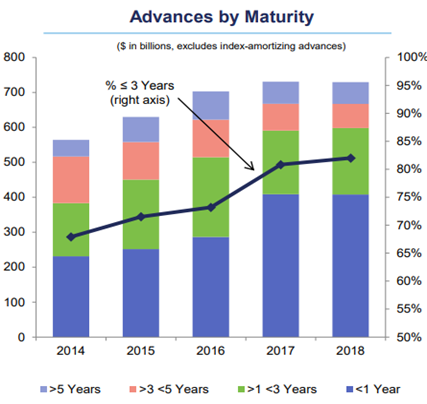

Another side effect is the increasing reliance of the FHLB system on short-term funding. Over the recent years, there has been an increasing asset-liability mismatch, with tenures of advances growing longer (Figure 7) while funding takes place increasingly on the short end of the maturity spectrum (Figure 8).

In a speech at the FHLBank Directors conference on May 2017, Federal Housing Finance Agency Director Melvin Watt raised this issue, mentioning concerns over potential rollover risk of short-term liabilities, particularly in a period of rising interest rates.

Figure 7 & 8: FHLB Asset – Liability Maturity Mismatch

Source: FHLBanks Office of Finance, Investor Presentation, May 2019

Source: FHLBanks Office of Finance

According to Baghai, Giannetti and Jäger (2019), this gap may have been offset by offshore MMFs, predominately from the Euro area, as seen in Figure 9. This figure uses European Central Bank (ECB) data to illustrate the asset composition of Euro area MMFs, with an internal/external distinction made for fund assets originating from companies registered in the Euro area and those outside. Following the implementation of the reform, external assets seem to have increased, presumably as Euro-area offshore MMFs soaked up the excess supply of domestic high-quality short-term paper. One possible complication here relates to a potential overreliance of certain issuers on offshore funds as a continuing source of funding. Divergence in regulatory standards across different jurisdictions may expose high quality domestic issuers to unexpected risks arising from weaknesses in offshore regulatory standards.

Figure 9: EU MMF Assets by Issuer Origin

Source: Liability Structure and Risk-Taking: Evidence from the Money Market Fund Industry

Comparison to the European MMF Reform

The European approach to MMF reform provides an interesting point for comparison of policy impacts on the state of the industry. Formally concluded on March 21st, the reform carries some similarities to its US counterpart in terms of higher liquidity requirements and the potential imposition of fees and gates on withdrawals, though the EU version requires that be the case for constant net asset value (CNAV) funds also. The reform also contains some differences, such as the explicit prohibition of external support for MMFs. Perhaps most notably, it spelled the creation of a third type of MMF, the limited variability NAV (LVNAV) fund, which acts as a compromise between the variable NAV (VNAV) and constant NAV (CNAV) funds of the US. LVNAV funds maintain a stable share-value as long as the underlying NAV is within a 0.20% band of their currency unit. On the other hand, if the NAV breaks that band, the fund converts to a variable NAV. This implies that LVNAV funds would behave as CNAV funds in a low volatility environment but could convert to VNAV funds during periods of stress.

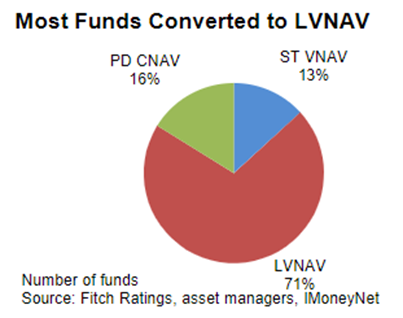

The similarity of this vehicle to the previous status quo for prime funds in Europe has been viewed positively by investors. Following the reform, the majority of prime assets (Figure 10) landed in LVNAV funds.

Figure 10: EU MMF Assets by Fund Type (As-of 3/21/2019)

Source: Fitch Ratings

In this environment, flows appear to have been driven by perceived confidence in managers’ ability to maintain the LVNAV fund’s CNAV-like utility. As such, there are management incentives to ensure the funds remain within the 0.20% band that enables them to resemble CNAV funds. While the European regulation also resulted in higher research costs for cash investors, the retention of prime MMFs deposit-like utility through the LVNAV vehicle prevented the type of outflows seen in the US. At the same time, LVNAV portfolios can be expected to be safer than the pre-reform CNAV prime funds from a credit and liquidity standpoint. Securities maturing within 75 days are valued using amortized cost, which would render them desirable to mangers of LVNAV funds. While risk is not entirely mitigated in the case of an LVNAV fund run, the ability to impose fees and gates serves to limit the potential market disruption of such an event. Nevertheless, given the recency of the implementation of this reform, how it performs during periods of market stress remains to be seen. It is not impossible that given the popularity of LVNAV funds, a period of market stress could result in lumpy flows and potential funding disruption at a time when it would be least desirable.

Potential Risks on the Horizon

While the dust following the reform’s implementation has mostly settled, the new money fund landscape has yet to be tested. To add to the observations made in the previous sections of this paper, we see certain risks on the horizon that may present challenges for cash investors.

From a broader perspective, challenges to the outlook relating to the US-China trade dispute could affect the money markets through direct effects on impacted corporate issuers’ credit health, while its implications for global growth could affect credit and liquidity conditions more broadly. Uncertainty over Brexit’s final form and associated economic consequences add further uncertainty to the outlook. Market participants have also expressed some unease with the rise of corporate leverage over recent years, which can have potential implications for the now riskier prime portfolios in the event of a downturn. Our February whitepaper, Corporate Leverage: Par for the course or harbinger of an upcoming crisis?, looked at the state of corporate leverage and its potential implications for cash investors.

Another interesting development is the emergence of new debt classes as the result of differing regulatory approaches to TLAC (total loss-absorbing capacity) requirements. New types of senior “bail-inable” debt are likely to become more commonplace as banks work to meet their regulatory requirements. These debt types, while still untested, could conceivably find their way into cash portfolios on account of their investment grade ratings and higher yield, thereby increasing the structural complexity of these portfolios and introducing added sensitivities to idiosyncratic factors impacting those issuers.

Lastly, political uncertainty over the debt limit, as the treasury’s extraordinary measures are likely to run out by November, could have consequences for the broader financial markets. Our September 2017 whitepaper, The Debt Limit with Complications from Money Market Funds, provides a look at the potential implications of a protracted congressional debt limit fight in the context of a post-reform world.

Recommendations for Cash Investors

The MMF reform has by design raised the importance of due diligence for cash investors. By decreasing the deposit-likeness of prime MMFs, there are now fewer options for capturing market yields while also limiting the risk of principal losses. For prime investors, credit research and monitoring needs are now greater, given the closer link between portfolio quality and value preservation. Investing in prime funds today requires greater research capabilities, which may not be available to all investors. While the post-reform funds are overall more resilient than before, there is also now a greater divide between overnight liquidity and yield, as well as more room for differentiation across fund managers. While government funds have retained their utility as sweep vehicles for overnight liquidity, the reform’s stricter maturity and liquidity requirements have also limited their yield advantage over bank deposits. In this context, direct purchases or separately managed accounts (SMAs) can be a viable option for investors seeking solutions customized to their risk and return goals. By managing a portfolio to an individual mandate, investors can outsource credit research costs while achieving individualized liquidity and retaining the opportunity to exploit market inefficiencies. We have several whitepaper articles on the subject of SMAs as they compare to shared liquidity cash vehicles and welcome readers to visit our website for details.

Conclusion

In this whitepaper, we examined some of the second order effects of the 2016 money fund reform, its overall impact on funding markets, how it compares to its European counterpart, and the extent to which it met regulators’ goals of improving industry resilience. We reviewed research showing that the introduction of fees and gates and a floating NAV changed investors’ perception of prime MMFs, creating incentives for fund managers to take on more credit risk. The asset migration from prime to government, combined with the rise in demand for riskier assets, resulted in changes in the demand dynamics of short-term funding markets which were mitigated by greater involvement of the FHLB system and offshore funds in funding intermediation. This outcome increases the dependency of large domestic financial institutions on FHLB’s status and creates some sensitivity for highly rated domestic corporations to foreign operating environments.

We find that the middle-of-the-road European approach to MMF reform, while still untested, resulted in less disruption in the European funding markets through the creation of LNAV funds that maintain some of the original utility of CNAV prime funds, while also driving higher fund liquidity and portfolio credit quality. This approach, however, may come at the expense of yield and possibly fund flow volatility during times of market stress, which could exasperate funding pressures.

Lastly, we conclude that the US MMF reform of 2014 did indeed improve the resilience of the MMF industry by strengthening liquidity and making investors’ exposure to fund portfolios explicit in the case of prime funds. However, the accompanying risk-taking incentives work counter to the reform’s original intentions. Given fund sponsors’ exposure to fund performance, one suggestion by Alnahedh and Baghat (2017) has been to ensure there is sufficient capitalization at the sponsor level to counter their added off-balance sheet risk exposure to the MMF portfolio. At the same time, changes to fund compensation structure to focus on creating and sustaining long-term sponsor shareholder value might be a step in the right direction. While the utility of MMFs has become less universal post-reform, cash investors may benefit from evaluating alternative cash management strategies that can better align with their liquidity needs, credit risk tolerance and yield requirements.

DOWNLOAD FULL REPORT

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

1A good determiner of ‘moneyness’ comes from Pennacchi and Gorton (1990), and states that securities are considered to be money-like if they can be traded by uninformed agents.

2In this case iMoneyNet & CraneData.

3Federal housing Finance Agency, Prepared Remarks of Melvin L. Watt, Director of FHFA at 2017 Federal Home Loan Bank Directors’ Conference, May 23, 2017

4LCR requirements require banks to hold enough High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) to meet liabilities maturing in 30 days. By substituting mortgages from the bank’s book with FHLB advances, banks are able to increase their stock of HQLA.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.