Shaping Investment Policies for a Safer Cash Portfolio

Abstract

We set out to answer 10 of the most common questions that arise when writing investment policy statements (“IPS”) for cash portfolios. In doing so, we will provide a number of peer group data comparisons to add insight and context to the process.

The 10 questions focus on the following subjects of investment policy statements:

- Maximum liquidity limits

- Minimum credit ratings

- Concentration limits

- Percentage of portfolio in overnight liquidity

- Benchmark selection

- Appropriateness of ABS and MBS for cash portfolios

- Prohibited transactions

- Conflicts of interest

- Monitoring of portfolio performance

- Resolution of out-of-compliance items

Revision Note

Since our earlier revisions, the treasury investment management landscape has continued to undergo major changes that require a fresh look at how corporate investors construct their investment policy statements. The general guidelines contained in the Appendix still serve as a quick reference guide for key components in an IPS. This revision also offers a side-by-side view of the preferences of Capital Advisors Group’s (CAG’s) client universe in 2019 versus 2015.

In general, we find that investors haven’t materially altered limits on maximum maturity or credit ratings, they have reduced issuer-based concentrations, and they have cut down the use of asset-backed securities as permissible investments. We hope this update provides additional helpful insight for institutional investors in their own IPS construction or revision efforts.

Introduction

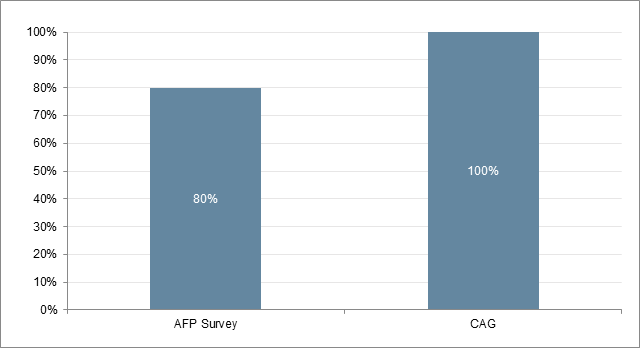

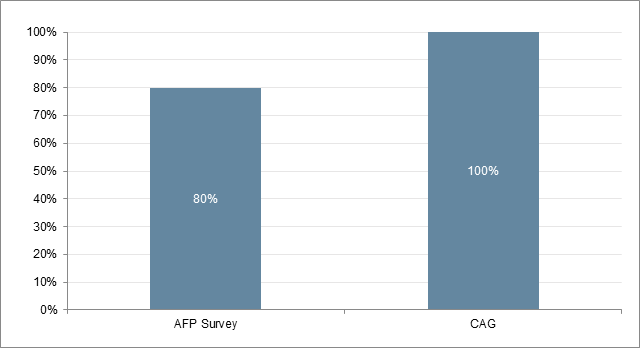

Investment policy statements, also known as investment guidelines, are widely used as important control documents in investment accounts. A recent industry survey showed that approximately 20% of corporate cash investors do not have written investment policies1. It also is quite common for some investors to permit wholesale adoption of policy guidelines recommended by outside investment managers, even though such recommendations may not always be in the best interests of the investors.

Figure 1: Do You Have a Written Cash Investment Policy?

Source: AFP 2019 Liquidity Survey and Capital Advisors Group, Inc.

Over almost three decades of helping clients to develop and review investment policies, we understand the delicate balance needed when writing an IPS – the document needs to provide flexibility for an investment manager to realize higher return potential while clearly defining its risk management functions. Instead of producing a “how-to” manual on writing investment policies, we will focus on some of the common issues faced by cash investors during the investment policy development process. Wherever applicable, we will provide peer group data from corporate cash investors. Some of the information comes from our own client database and some of it from third-party surveys. We hope that such peer group data will add helpful insight to the process.

1. What Is an Appropriate Maximum Maturity Limit?

We believe that an IPS should have a long-term view to maximum maturity tolerances that will cover most interest rate environments. While interest rate cycles come and go with regularity, investment policy revisions often involve time-consuming board meetings and audit committee debates. It is neither efficient nor practical to constantly revise maturity limits to adapt to new interest rate situations. Therefore, the investment policy should define the investor’s maximum risk tolerance and allow management and the investment manager to make tactical decisions within that tolerance when appropriate.

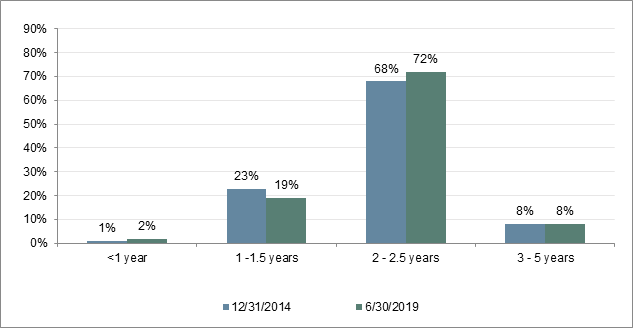

As of 6/30/19, approximately 72% of CAG’s institutional cash accounts choose 24 months as their permissible maximum maturity limit. This is only slightly higher than the 68% of clients who reported that limit in December 2014. The relatively small shift demonstrates our clients’ relatively stable long-term view of their maximum maturity tolerances despite evolving interest rate expectations in the last three years.

Figure 2: Maximum Maturity Limits of Capital Advisors Group’s Clients

Source: Capital Advisors Group, Inc. as of 6/30/19

2. What Is an Appropriate Minimum Credit Rating?

The use of credit ratings from national rating agencies is a good first step for controlling credit risk. Some investors are restricted by federal or state laws to invest only in U.S. Treasury and Agency debt, but most corporate cash investors tend to be comfortable buying investment grade, non-government securities, and with good reason. According to Moody’s Investors Service, only 0.09% of issuer-weighted investment-grade corporate bonds failed to make payments on time within a year of issuance (with data from 1983 through 2018). Over a three-year period from the original date a bond was issued, that figure increased to 0.43%2.

All three major rating agencies—Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch—use four letter grades to set investment-grade ratings (e.g., BBB, A, AA, and AAA). The agencies then apply finer degrees of upper, mid and lower numerical ratings (e.g., A1, A2, A3 from Moody’s) within a letter grade rating to further indicate relative credit quality. Although a BBB credit rating is still investment grade, many cash investors prefer to purchase securities rated A or higher. In the event an A-rated security is downgraded, this allows for an added buffer before it slips into non-investment grade or “junk” status. The same Moody’s study indicates the payment default probability of corporate securities rated A or higher to be less than 0.05% within a year and less than 0.35% cumulatively within three years3.

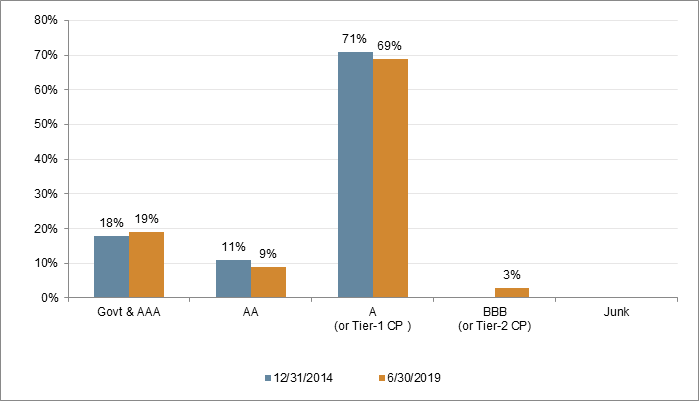

Figure 3: Distribution of Minimum Credit Ratings by Capital Advisors Group’s Clients

Source: Capital Advisors Group, Inc.

Figure 3 shows that there has been a slight uptick in investment policies allowing for investment in BBB and Tier-2 securities today versus in 2014, although the vast majority of Capital Advisors Group’s clients continue to require a minimum rating of A.

Cash investors with more stable cash balances, lower liquidity needs, and higher risk tolerance may explore the possibility of assigning BBB as minimum accepted credit ratings. Since 2015, the BBB market has grown in both size and prominence. As ratings continue their systematic downward drift, BBB debt is becoming a more attractive option for cash investors who maintain strict concentration limits while looking for high-quality names and significant return over government securities. Even so, limits on the purchase of BBB rated debt are generally quite stringent.

BBB-rated corporate bonds have the positive attributes of broader supply, improved risk diversification, moderate default and ratings migration risk, and attractive yield potential. These attributes need to be viewed in the context of treasury management organizations, which tend to emphasize principal preservation and liquidity more than income objectives in their investment portfolios. Although BBB-rated corporate securities are of investment grade quality, market acceptance tends to be more limited. The lower acceptance often leads to lower secondary market liquidity, as fewer potential buyers are available. Liquidity risk may be at least partially mitigated by staying shorter. Additionally, it would be a mistake to think that all BBB-rated debt is alike. The creditworthiness of an issuer depends on many factors, including its business model, operating and financial conditions, and susceptibility to external factors. Decades of empirical evidence has shown that ratings on financial firms tend to be more volatile due to the confidence-sensitive nature of their business models and reliance on market funding. Staying with non-financial issuers may help limit ratings risk and reduce market value swings. Lastly, we believe that BBB debt should be used as a limited part of a conservatively structured portfolio.

For more information, refer to our July 2019 white paper, “Do BBB Corporate Bonds Belong in Treasury Management Portfolios?”

3. What Is an Appropriate Concentration Limit?

Issuer concentration limits are another important tool to control the idiosyncratic credit risk of individual issuers. Theoretically, the lower the concentration limit, the better risk diversification benefit there is to the investor. In practice, however, the dollar size of a cash portfolio often influences the degree of issuer diversification. This is because portfolio holdings tend to become less liquid, and less desirable to a potential buyer, when they fall below certain sizes – a few million in par value for short-term corporate bonds, for example.

The risk of over-diversification becomes especially evident with financial issuers when liquidity and credit support tend to focus on a few systemically important financial institutions. Smaller, less capitalized issuers in peripheral markets may suffer substantial liquidity shortage and investor confidence and may run into unexpected credit issues. Interested readers may refer to our July 2010 white paper, “Prudent Risk Diversification.”

For a relatively small portfolio, a concentration limit of 10% to 15% for short-maturity securities rated A or higher may be appropriate. As the portfolio size increases, the limit may be reduced to 5% or lower. Securities issued and guaranteed by the U.S. federal government typically are exempt from concentration limits as they often are perceived as risk-free. Government-sponsored enterprises, including Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the FHLB System, typically enjoy higher issuer limits (such as 25%) because of their implicit support from the federal government.

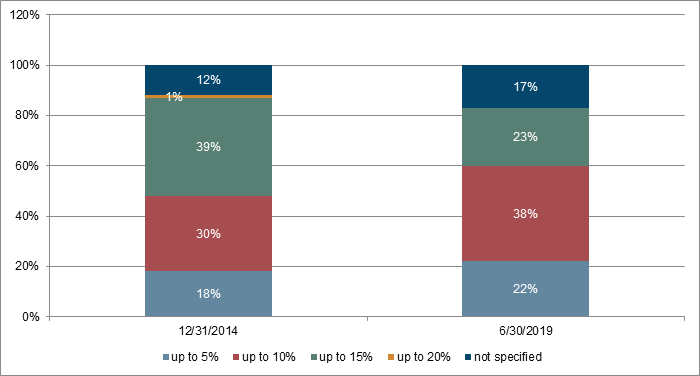

Figure 4: Distribution of Issuer Concentration Limits at Capital Advisors Group

Source: Capital Advisors Group, Inc.

Alternatively, investors may incorporate credit ratings into concentration limits, placing lower limits on securities with lower ratings. At Capital Advisors Group, about 38% of our institutional cash accounts allow for a 10% concentration limit per issuer, while 23% permit a 15% issuer concentration, as of June 2019. More investors moved to a lower limit versus 2014.

4. What Portion of My Portfolio Should Be Available Overnight?

Not all investors specify how much of their portfolio should be in money market funds or other overnight instruments as an investment policy item. For investors who regularly withdraw funds from their cash accounts, it may be appropriate to have certain liquidity buffers for scheduled withdrawals and to compensate for cash flow forecasting errors. The predictability of cash flow and the investor’s risk tolerance should dictate the portion of the portfolio allocated to liquid funds.

It is worth noting that a well-managed portfolio should be able to provide for unexpected liquidity needs through the sale of liquid assets in a reasonably quick fashion. Still, selling securities prior to maturity may result in undesirable capital gains or losses. Interested readers may refer to our December 2011 white paper, “Maintaining Liquidity in Corporate Cash Accounts,” on how to define liquidity and use its characteristics effectively to meet liquidity goals.

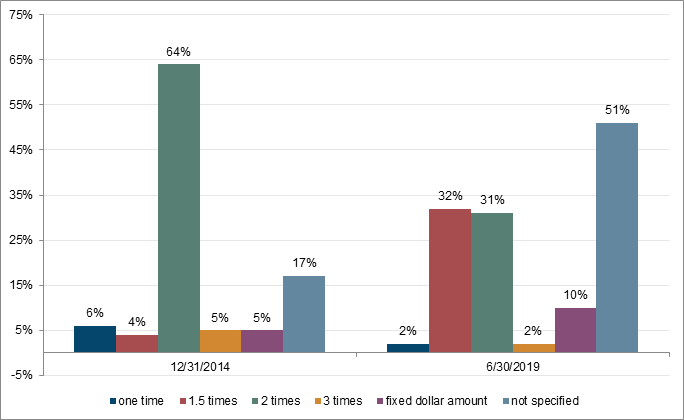

Figure 5: Percent of Portfolio Required in Overnight Funds Measured by Multiples of Monthly Cash Needs

Source: Capital Advisors Group, Inc.

5. How Do I Choose an Appropriate Performance Benchmark?

A relevant policy issue to consider when making benchmark selections is that a good benchmark should reflect the “neutral” position for a given policy. If the investment strategy and the securities it allows for are substantially different from those of the benchmark, then the portfolio may be taking on too much benchmark risk.

A unique challenge faced by cash investors is that the most popular fixed income indices measure total return, which includes unrealized gains and losses. While market value changes in a portfolio certainly are important to monitor, most cash investors do not receive a real benefit from the gains or suffer unrealized losses if they intend to hold the investments to maturity. Instead, these investors generally are more concerned with the yield they are earning based on the securities’ book values.

For relatively short buy-and-hold accounts, we generally use money market peer group averages, such as the Lipper Institutional Money Market Funds Average, as a benchmark. Since these funds use securities’ book values as their principal values, all of their returns effectively come from income, making the returns more directly comparable to cash accounts. A 90-Day Treasury Index also may be a reasonable benchmark to use. For portfolios containing securities longer than a year, a market index with a comparable duration may be more appropriate. In a nutshell, a good benchmark should be simple, objective, representative and publicly available.

6. Are Asset-backed or Mortgage-backed Securities Appropriate for Cash Portfolios?

Unlike corporate bonds with specific maturity dates, asset-backed securities (“ABS”) and mortgage-backed securities (“MBS”) use a calculated number called “average life” to estimate the expected full principal payment date. To compensate for cash flow uncertainty, ABS and MBS tend to use structural enhancement tools to enable them to attain strong credit ratings (often AAA) and may offer attractive yields relative to corporate securities.

In a stable or improving consumer credit environment, cash investors may be able to benefit from ABS backed by credit card receivables and automobile loans. For credit card ABS, issuers often use a structure called a “soft bullet” to ensure that all the funds necessary to pay down the full principal of the bond are accumulated in a reserve account prior to the expected maturity date. In an automobile loan ABS, the expected full principal payment dates also are fairly predictable, usually within a few months, since relatively few car loan borrowers regularly refinance their loans.

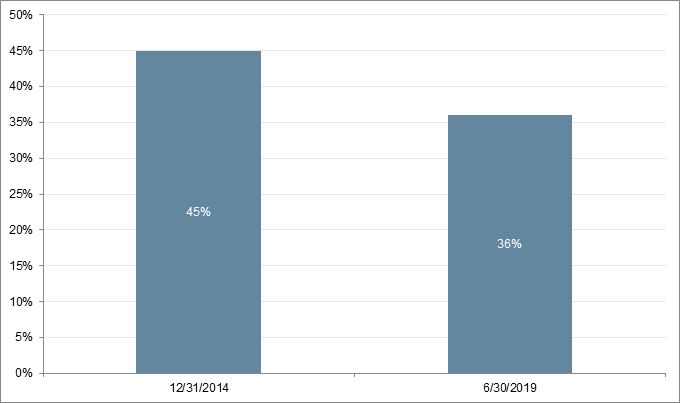

Figure 6: Percentage of Accounts Listing ABS as Approved Assets

Source: Capital Advisors Group, Inc.

Figure 6 indicates that the percentage of Capital Advisors Group’s clients allowing ABS has decreased from 45% in 2014 to 36% in 2019. We continue to view AAA-rated credit card backed ABS as consistent with most corporate cash investors’ credit and liquidity requirements. This is especially true today, when the short-duration market lacks high quality securities with reasonable yield potential. Auto ABS, however, we view as less desirable given where we are in the cycle. Currently, the auto loan market is relatively weak in terms of underwriting and credit quality standards, and as a recent Standard & Poor’s report4 points out, auto loan terms are lengthening resulting in reduced credit quality and liquidity of auto ABS versus credit card ABS.

For MBS securities, changing interest rates may have a major impact on mortgage refinance activities. The average life of MBS securities, including those designed to reduce cash flow fluctuations (collateralized mortgage obligations), can swing many months or years either before or after the expected payment date. Investors who rely on predictable cash proceeds to fund their treasury operations, thus, may find MBS less attractive than those who do not have such constraints. We think investors who approve MBS in their IPS should limit their investments to securities backed by agency mortgages instead of bonds backed by higher-risk, “non-conforming” mortgages.

7. What Would You Consider Prohibited Transactions?

As an additional measure of risk control, it may be a good practice to prohibit certain securities or procedures that are inconsistent with the principal protection, liquidity and yield objectives of cash investing. What one may put on this list is an individual choice based on objectives, risk preferences, and historical experience of the investor. An important point to remember is not to “throw the baby out with the bath water.”

Examples of prohibited securities may include common or preferred shares of equity, unrated or non-investment-grade securities, exotic forms of derivatives, the purchase of securities on margin or other types of financial leverage, and investments in physical real estate, venture capital or commodities, among others.

8. How Do I Address Investment Manager Conflicts of Interest?

A conflict of interest may exist when the manager of an investment portfolio has an interest with respect to the invested assets that may impair his or her ability to render unbiased advice or to make unbiased decisions affecting the investments. An effective investment policy should contain explicit language safeguarding against such conflicts.

The formal adoption of the “prudent person rule” in an IPS may help set the ground rule. The “prudent person rule” is a common law standard applied to the investment of trust funds. The rule directs a fiduciary “to observe how persons of prudence, discretion and intelligence manage their own affairs, not in regard to speculation, but in regard to the permanent disposition of their funds, considering the probable income, as well as the probable safety of the capital to be invested (Harvard College v. Amory (1830) 26 Mass (9 Pick) 446. 461).”

Although most institutional assets in pension and endowment funds are managed by SEC-registered investment advisors, some investors in the cash management space have retained securities brokerage representatives as managers. Interested readers may refer to our July 2008 white paper, “An Old Favorite Faces a New Paradigm,” for our commentary on the broker cash management model.

9. How Do I Monitor My Portfolio Performance?

Investment management is a dynamic process and cash portfolios are no exception. Formal procedures should be in place to review the portfolio on a regular basis – at least quarterly. The policy document should detail the frequency and subjects to be reviewed, as well as the persons responsible for such reviews. In addition to investment performance, other items to review may include the accuracy of cash flow projections, earned income estimates, credit rating changes and unrealized gains and losses in the portfolio, among others. The policy itself should be reviewed periodically, preferably annually, to assess its effectiveness in risk management and to reflect the changing investment environment.

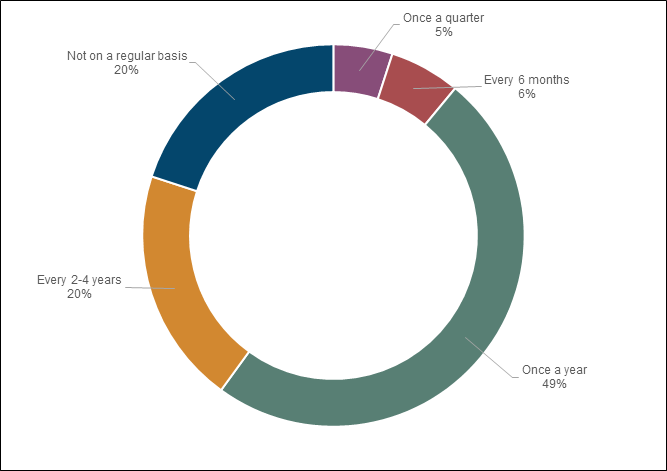

Figure 7: How Frequently Is Your Investment Policy Updated?

Source: AFP 2019 Liquidity Survey

Figure 7 is taken from the most recent annual liquidity risk survey of corporate treasury professionals conducted by AFP. The survey results show that nearly half of respondents typically review their investment policies annually.

10. How Do I Resolve an Out-of-compliance Item?

Due to the dynamic nature of business and investment environments, it is not uncommon to have an out-of-compliance situation in a cash portfolio. It is imperative to anticipate such situations in an investment policy and to include proper guidelines for issue resolution and escalation. It is impractical to list every type of out-of-compliance problem, but it may be helpful to address them using three general principles: materiality, timing and authority.

- Materiality: Will the portfolio incur a loss and, if so, what is the severity of the loss?

- Timing: Do I wait and let the problem cure itself or do I take action to remedy the current situation and to prevent future problems?

- Authority: What is the chain of command in making discretionary decisions regarding the first two principles?

For example, consider a portfolio with a minimum credit rating of A3: If a security representing 3% of the portfolio with three months of remaining maturity was downgraded to Baa1, the CFO may have the discretion to authorize the manager to continue holding it to maturity rather than force a sale.

Conclusion

Investment policy statements are important investment documents that can help corporate investors achieve risk management objectives and help outside investment managers clarify clients’ restrictions so that they may deliver expected results. Careful implementation of a well-crafted, written policy statement is an important part of a successful cash investment strategy that also may help to improve investor-manager communications.

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

1Association for Financial Professionals, Inc. 2019 AFP Liquidity Survey.

2Sharon Ou, et al, Special Comment: Annual Default Study: Corporate Default and Recovery Rates, 1920-2014, Exhibit 22: Average cumulative credit loss rates by letter rating, 1982-2014, Moody’s Investors Service, March 21, 2015.

3Ibid.

4https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/190730-u-s-prime-auto-loan-abs-are-seeing-more-back-loaded-losses-as-loan-terms-lengthen-11079750

Appendix: Introduction to Investment Policy Statements

What Is an IPS?

An IPS is a written document outlining the process for an investor’s investment-related decision making. The purpose of an IPS is to formally describe how investment decisions are related to an investor’s goals and objectives. A well-constructed IPS provides evidence that a clear process and a methodology exist for selecting and monitoring cash investments.

The Benefits of an IPS

In retirement plan administration, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) stipulates that a plan sponsor has a fiduciary obligation to document the procedures for investment selection and evaluation. While such a requirement is not equally placed on cash managers, the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act placed strong demand on a corporation’s internal control procedures. The existence of a well-constructed investment policy statement provides evidence of a prudent investment decision-making process and, in doing so, it can serve as an important risk management function in defense of potential fiduciary liability claims.

Beyond the legal and regulatory reasons for adopting an investment policy statement, creating an IPS forces a corporation to put its investment strategy in writing and commit to a disciplined investment plan. It’s both a blueprint and a report card. The ever-increasing number and variety of outside investment advisors also make it necessary for a corporation to develop an investment policy so that the managers’ expertise can better match the investor’s risk tolerance, liquidity constraints and return expectations. Furthermore, a written policy may help those responsible for investment decisions avoid the temptation of following short-term “fads” in the financial markets.

A Typical IPS

An investment policy statement’s content always should be customized to the investor’s specific needs. Some corporations prefer to adopt a brief investment policy statement summarizing the critical aspects of their investment goals and decision-making processes, while others prefer a more detailed version that addresses topics more specifically. The following areas often are addressed in an investment policy statement:

- Purpose

- Investment Objectives

- Eligible Investments

- Concentration Limits

- Maturity Limits

- Liquidity Requirement

- Credit Quality

- Marketability

- Trading Guidelines

- Custody of Assets

- Fiduciary Discretion

- Monitoring and Reporting

- Manager Selection and Termination

- Benchmarking

- Fees

- Future Amendments

Resources from Investment Managers

Investment managers, including Capital Advisors Group, often offer sample investment policies to prospective clients for use as references to draw up their own policies. The investment managers often are involved in the ongoing efforts of reviewing and revising current polices. It is advisable for institutional investors to tap into this pool of resources and discuss certain aspects of an investment policy with independent advisors before formal policy adoption.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.