Past Mistakes Haunt Fed’s Inflation-Fighting Plans

The Fed shifted its policy stance radically at its December meeting, increasing the pace of its reduction in asset purchases and pushing up the timeline for rate hikes. This move was a culmination of policy being out of sync with the state of the economy, as it was extremely accommodative even with above target inflation and a tight labor market. There is a significant amount of uncertainty regarding the path forward from here, as Omicron and inflation loom large. However, the new projected path of policy sets a realistic baseline expectation for investors in 2022.

Introduction

The Federal Reserve has commenced the tapering of its Quantitative Easing (QE) program. At a projected rate of $30B a month, the tapering of the originally, $120B monthly asset purchase program is on pace to be completed by March 2022. Prior to the start of asset tapering, the Fed laid out its plan in painstaking detail to end QE. It issued specific guidance on when tapering would be appropriate, even going so far as devoting its June meeting to “talking about talking about tapering.” They did this with an eye on avoiding the mistakes of the past.

In 2013 when then Chair Ben Bernanke announced that the Fed was considering tapering QE3, he ran into a buzzsaw. Markets panicked, Treasuries shot upwards, equities sold off, and traders rushed to price in premature rate hikes. Having learned from the past, the Fed avoided those land mines this time. However, until recently they were facing a different problem, their accommodative policy was out of sync with the state of the economy.

Inflation

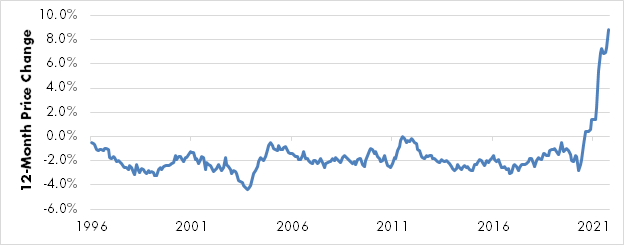

This disconnect is most obvious in the inflation data. CPI inflation hit a 30-year high of 6.8% in November, with core CPI not too far behind at 4.9%. PCE inflation, the Fed’s preferred gauge, is running slightly lower but still well north of 2%. These numbers represent the apex of a trend seen since earlier this year, in which supply chain bottlenecks combined with excess consumer demand led to acute shortages of goods (varying from used cars to furniture). The resulting impact on prices of durable goods bucked a 25-year deflationary trend.

Figure 1: Durable Goods Prices (PCE Price Index)

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED), Bureau of Economic Analysis.

As Fed officials noted, there is a distinct possibility that a combination of easing supply chain pressures and a shift in spending from goods to services leads to an abatement of inflationary pressures in 2022/23. Hence, the Fed’s frequent use of the word “transitory” in describing inflation throughout the summer and fall.

However, there are reasons to suspect that inflation may be more persistent. Excess consumer savings, remaining government support measures, and rising wages are all acting to support demand. This could put a floor under inflation even if supply chain problems clear.

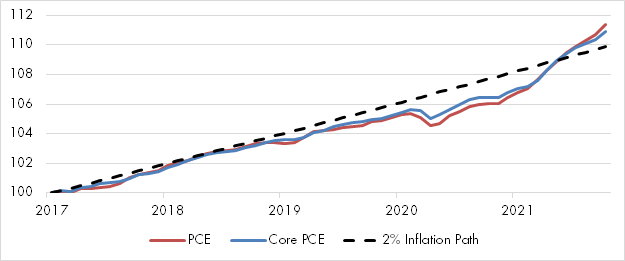

Moreover, whatever the path of inflation, the Fed’s inflation mandate has already been met. The Fed’s relatively new Flexible Average Inflation Targeting framework gives it some room to overshoot its 2% target to compensate for past periods of undershooting. However, the current surge in inflation has more than offset past periods of low inflation when viewed over any reasonable time frame.

Figure 2: PCE Price Index (2017=100)

Source: FRED, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

And inflation expectations point towards inflation remaining at or above target for the foreseeable future. The 10-Year Market Breakeven Inflation Rate (a proxy for inflation expectations over the next ten years) hit 2.7% in November, its high point over the past decade.

Figure 3: Inflation Expectations

Source: Bloomberg, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Under these conditions there is no question that the Fed has already exceeded its inflation target.

Labor Market

The labor market is a more complicated issue. The economy is still some 4 million jobs short of where it was pre-pandemic, and the unemployment rate is still 0.7% higher than its recent pre-pandemic low of 3.5%. This would seem to suggest that there is still a significant amount of slack in the labor market. However, this obfuscates the impacts the pandemic has had on the labor market.

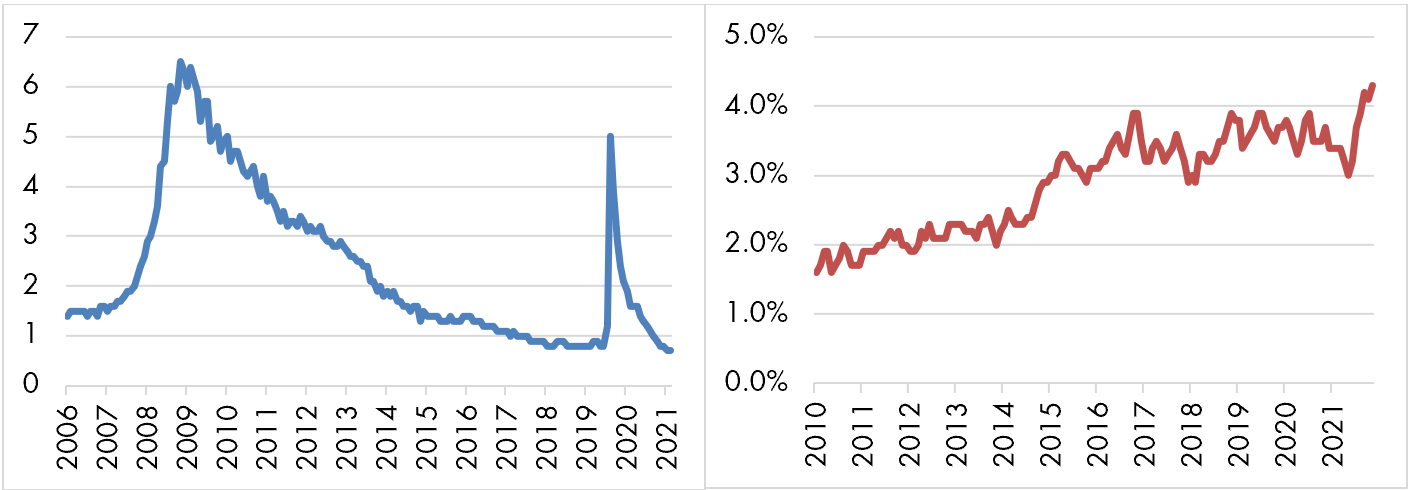

The pandemic resulted in a significant shock to labor supply. Record numbers of workers dropped out of the labor force for a variety of reasons, ranging from health concerns to early retirement, and immigration ground to a halt. At the same time, labor demand remained steady as consumer spending and government stimulus measures propelled the economic recovery. This mismatch between labor supply and demand has resulted in acute labor shortages across a variety of different industries, as firms have been competing to hire an ever-smaller pool of available workers. The number of job openings relative to unemployed workers is now at an all-time high, as is the quits rate, suggesting that the balance of power lies with workers rather than firms. Combined with rising wages, these signals run counter to the employment gap, suggesting that labor conditions are rather tight.

Figure 4 & 5: Unemployed Persons Per Job Opening & Median Wage Growth (3-Month Average)

Source: Atlanta Fed, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Policy De-Facto Easing

The final reason why the Fed’s policy was out of sync with the economic situation is de-facto easing. Despite the tapering announcement, monetary policy continued to ease throughout the fall. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the TIPS markets, where rising inflation expectations sent 10-Year Treasury Inflation-Protect Security (TIPS) yields to -1.1% in mid-November, their lowest level since their inception in 1997. Since TIPS are a proxy for the real interest rate, this portends that the real cost of borrowing was at its lowest level in 25 years, significantly below where it was during the height of the pandemic.

Figure 6: 10-Year TIPS Yield

Source: FRED, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Given how far output, employment, and inflation recovered from the nadir of the crisis, this policy stance was becoming increasingly inappropriate. It ran the risk of running the economy too hot and de-anchoring inflation expectations, thereby leading to sustained levels of higher inflation.

A worst-case scenario can be derived from The Great Inflation during the 1970s, when a combination of an oil shock, easy monetary policy and rising wages resulted in a prolonged period of high inflation (peaking at 15% in 1980). In response, Fed Chair Paul Volcker had to embark on an extreme course of monetary tightening, restricting growth of the money supply and pushing the Fed Funds rate north of 19% in 1981. This achieved its desired effect, beginning the period of low and stable inflation the economy has been in ever since. However, the collateral damage was significant, as the economy entered a severe recession that sent the unemployment rate above 10%.

Policy Shift

Bottom line, to dampen the risk of a Volcker-like scenario the Fed needed to rethink its policy outlook. This shift began in late November, as Chair Powell dropped the term “transitory” from the Fed’s lingo, saying that inflation was more persistent than previously anticipated. He also noted that despite the rise of the Omicron variant the Fed was prepared to increase the pace of tightening to deal with the reality at hand.

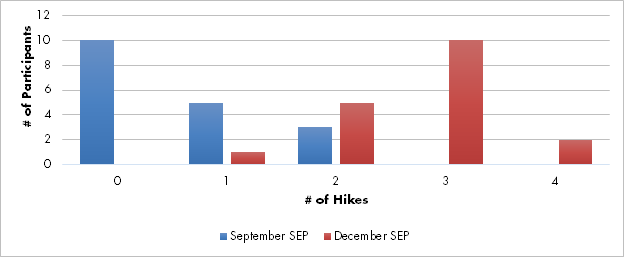

In line with this, at its mid-December meeting, the Fed took aggressive actions to reign in policy support. It started by increasing the pace of the taper, from $15B to $30B a month, pushing in the timeline for the end of QE from June to March. More significantly, the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) showed that the median FOMC participant was now projecting that the Fed would hike rates three times in 2022. This was a marked increase from the median projection of zero hikes in September’s SEP.

Figure 6: FOMC Participants’ Projections for 2022

Source: Federal Open Market Committee.

Powell backed up these projections with relatively hawkish comments in his press conference, noting that demand was “robust,” and the labor market was strong. He acknowledged that full employment had yet to be reached, but that most participants (seemingly self-included) believed it would be reached next year. Moreover, he argued that the Fed was much closer to hitting its employment goal than its price stability goal, implying that policy support needed to be reined in to mitigate upside inflationary risks.

Looking Forward

The big question is whether this change in stance was too much or not enough. It’s early days, but it doesn’t seem as though the Fed has gone overboard here. Despite the shift in tone and policy, equity markets rallied after the news, and the dollar fell, suggesting that this will not dampen financial conditions (a key mechanism by which policy effects the real economy). This is likely because markets were ahead of the Fed in expecting tightening in 2022.

The spread of Omicron is an unknown here. Out of all the outstanding issues, this poses the greatest threat to the economic recovery and continued labor market progress. But while it’s too early to gauge what the impact of Omicron will be, the general trend has been that each wave of COVID infections has had less of an economic impact than the one proceeding it, as vaccines and treatments have become more available, and markets have adjusted to the realities of a reduction in face-to-face interaction. Notwithstanding this, Omicron also runs the threat of impacting inflation as much as the labor market, which could tie the Fed’s hands in responding to it.

That leaves the question of whether this will be enough. The early signs are positive as well, as TIPS yields have come in by 20 bps to -0.9% due to a fall in Treasury break evens, suggesting that the de-facto easing has ceased. Beyond this, it’s impossible to say much until the economic data starts coming in. The key question will be around the inflation narrative. Does the data suggest it is mainly supply driven, and thus will move back closer to 2% over time once these issues clear, or does it look to be more persistently demand driven? Outside of realized inflation, gauges such as inflation expectations, wage growth, and the employment cost-index (which Powell mentioned by name) will be key in making this judgement.

Finally, given the unpredictability of the situation, the Fed needs to adjust expectations for the predictability of the path of rates. Powell’s Fed has emphasized the use of data over forecasts, and this is the first real test of that moto. The outlook for monetary policy and the economy will shift as the next year unfolds. Actual policy should reflect that, grounding decisions in observed data and prioritizing optimal outcomes over predictability. In doing that, the Fed can keep small mistakes from spiraling out of control.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.