Why is Ireland the U.S. government’s third-largest creditor?

Ireland holds more than $300 billion of U.S. Treasurys, or does it?

It’s no surprise that economic juggernauts China and Japan keep swapping places at the top of the list of biggest U.S. creditors. What might strike observers as odd, however, is that tiny Ireland has been lurking at No. 3 for more than a year.

The country holds more than $310 billion in U.S. government paper, according to the Treasury International Capital, or TIC, report released on Monday.

But Ireland’s ranking is puzzling given that economic heavyweights with deeper financial markets, including the United Kingdom and Germany, keep less Treasurys on their books than an arguably peripheral member of the eurozone. Ireland does not have Japan’s massive pension fund and life insurance companies that need to buy long-dated government debt to match their lengthy liabilities. Nor does it have China’s exporters, whose rapid growth has enabled the country to accumulate its hoard of foreign-exchange reserves.

See: Why China has been gobbling up U.S. government paper

Investors and analysts suspect Ireland appears as one of the U.S.’s largest creditors on paper because Google parent Alphabet and other American corporations like to hold their overseas profits in highly liquid Treasurys. These cash-rich firms want to avoid the 35% repatriation tax, but they don’t want to let the foreign-earned cash sit idly by.

“There might be some correlation because U.S. corporations with European subsidiaries tend to hold most of their offshore corporate cash in Ireland and Luxembourg. Those are the two main places where they have their offshore cash,” said Lance Pan, director of investment research at Capital Advisors Group, which manages money for American firms.

As a country that offers a combination of low corporate taxes and an English-speaking workforce, it’s little surprise Ireland is now the country of choice for many U.S. companies looking for a launching pad for European operations. It currently hosts the European headquarters of Google US:GOOG , FacebookUS:FB , Apple US:AAPL and Microsoft US:MSFT

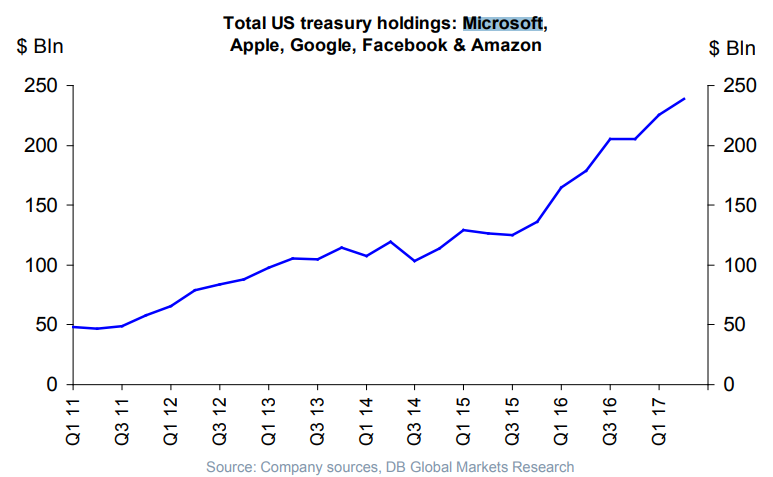

The four firms including Amazon US:AMZN , which has located its main office in Luxembourg, hold more than $200 billion worth of government paper, according to their corporate filings.

Microsoft and Apple alone added more than $80 billion of U.S. government paper in the past five years, doubling the previous amount. At the same time, Ireland’s holdings have grown at a similar pace, rising $200 billion since 2012.

Most of the sovereign paper in the country is placed in so-called custodial accounts. But the Treasury Department does not differentiate the composition and identity of the actual owners, and simply categorizes by nationality—in other words, central banks are lumped with private money managers.

This can lead to some curiosities in the data. Belgium’s well-documented hoard of U.S. debt, just shy of Ireland’s number, was partly due to the holdings of Brussels-based Euroclear, which facilitates trading for bonds and securities, and sometimes holds assets on the behalf of others. Some have speculated China used this very channel as a conduit for its purchases of government paper.

But to chalk up Ireland’s U.S. bond holdings as only reflecting its tax-haven status appears shortsighted.

Though Ireland is a financial center akin to Belgium, it “is a complicated case … it is not simply a reflection of its activity in financial intermediation,” said Brad Setser, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Plenty of hedge funds are based in Ireland, many of which might make sizable bets on the Treasury market. In fact, close to 2,500 hedge funds, private equity firms and real estate funds are based in the country, data from a trade body for local money managers show.

Until the U.S. introduces a tax holiday, if it does, Ireland will most likely keep its lofty place in the Treasury Department’s ranking, analysts believe.

As for the impact on the broader market, analysts are mixed. Some market participants have flagged concerns that corporate treasurers might act like flighty portfolio managers during market turmoil. In other words, when the bond market sells off, the likes of Apple and Microsoft could head for the exit door instead of holding tight, stoking the fire sale.

But Setser says treasurers don’t act like free-wheeling traders and their behavior is more akin to central banks. They’ll behave more like “reserve managers. They have more cash than they know what to do with,” he said.

What’s more, corporate treasurers tend to search for shorter-maturity debt with higher credit ratings, which are highly liquid, said Richard Piccirillo, a portfolio manager at PGIM Fixed Income.

These treasurers are typically “keeping it conservative, you do not want to realize losses on your security holdings …you have cash, you aren’t trying to earn a large return,” he said.

And as much financial heft as U.S. corporations carry, they pale against the punch of sovereign nations, which themselves have been unable to make a dent on the Treasurys market.

Even after China and Japan sold $211 billion of U.S. government paper over a 12-month period from February 2016, the 10-year Treasury note BX:TMUBMUSD10Y rallied from its post-election highs.