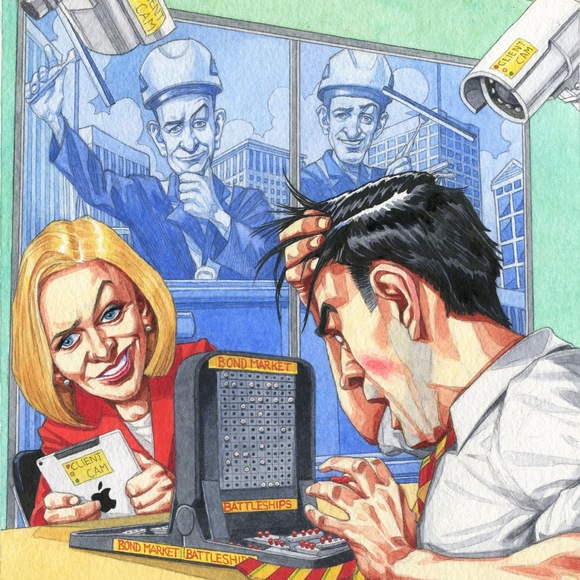

Pricing in the dark: how dealers lost their information edge

Asset managers may have an information advantage over dealers in bond pricing

- Need To Know

- Asset managers are emerging as effective liquidity providers in credit markets. “The most competitive pricing is from the buy side right now,” says a European bank’s head of bond execution services.

- Some say this is because the buy side has an information edge when it comes to bond pricing.

- “The information the buy side has is significantly superior to what the sell side has,” says one fund manager.

- Dealers have seen their price discovery mechanisms eroded by regulations and changes in market structure.

- Some banks are now moving to streamline the information they share with clients. “Banks will be thoughtful about where they distribute data,” says Chris Bruner at Tradeweb.

- Dealers are also taking steps to improve the way they handle market data and pre-trade information to aid price discovery.

In the final weeks of 2016, the head of bond execution services at a European bank was meeting with a trader at a big asset manager in New York when the conversation turned to the changing role of dealers in credit markets.

The buy-side trader was unusually forthright in his assessment. “I’m a price maker,” he told the banker. “I’ll tell you if I’m buying here or I’m selling there. Then, all the dealers that want to make a market in that bond will make one around my price. Price discovery starts with me.”

That will be music to the ears of trading platforms, which are counting on more assertive buy-side participation. But the growing confidence of these buy-side price makers has a flip side – the declining power of incumbent dealers. Put crudely, while buy-side firms have bigger portfolios and access to more sources of information on flows and positioning, dealers have smaller inventories and less insight to use when pricing. That is a reversal of the old order, which credit market participants say has become more apparent over the past year.

“The buy side has a clearer picture of where bonds should be bought and sold,” says the head of bond execution services. “The most competitive pricing is from the buy side right now. With less information, dealers will always have a losing hand.”

Some dealers are learning this the hard way. Chris White, chief executive of ViableMkts, a consultancy in New York, points to the example of Jefferies, which reported trading losses in 2015 after taking mark-to-market writedowns totalling $90 million across more than 25 energy bonds. Other banks have also seen losses in credit trading over the past year, he says.

The majority of people on the sell side are trying to figure out the picture, whereas on the buy side, you have the picture and are now figuring out what to do with it

Director of fixed income at a large asset manager in Boston

He blames the losses on the poor quality of pricing tools available to dealers. “Without better pricing data, the calculating and holding of risk is next to impossible,” says White, who previously ran the GSessions electronic bond-trading platform at Goldman Sachs. “Asking a market-maker to consistently provide liquidity in a market with no visible pricing is like asking a taxi driver to set the fare before knowing the destination. The market-maker is very susceptible to charging $20 for driving someone from Manhattan to the Hamptons.”

The buy side does not suffer from the same problem. “The information the buy side has is significantly superior to what the sell side has,” says the director of fixed income at a large asset manager in Boston. “Dealers call me all the time to check the price on certain less-liquid bonds. The majority of people on the sell side are trying to figure out the picture, whereas on the buy side, you have the picture and are now figuring out what to do with it.”

That reality is starting to sink in for sell-side firms. “An information asymmetry has definitely developed,” says the global head of market structure at a large US bank in New York. “Clients are getting more sophisticated.”

Trade reporting year zero

This is new, but the foundations were laid a decade ago. Prior to the introduction of trade reporting in 2002, if an investor wanted to know the market price of a bond, they had to call a dealer and ask for a quote. So dealers always knew who wanted to buy or sell and at what price, and they did a pretty good job of keeping this information to themselves.

That began to change as the market got more liquid and transparent, starting with the introduction of the US Financial Industry Regulatory Authority’s (Finra) trade reporting and compliance engine (Trace) for corporate bonds in 2002.

The price and volume of every corporate bond trade has been publicly reported on Trace shortly after execution since 2005 – giving bond investors a level of post-trade transparency comparable to equity markets. Academic research shows transaction costs for bonds eligible for Trace reporting fell roughly 50% immediately following its introduction.

Trace and other similar initiatives have helped level the playing field for investors in the credit markets. “In the US, you have bonds that are published on Trace within 15 minutes, and we’ve had success in Europe launching a similar trade-reporting tape called ‘Axess All’,” says Rick McVey, chief executive of MarketAxess in New York.

Rick McVey, MarketAxess: A more level playing field

Dealers have contributed to this shift by selectively sharing with clients a wealth of pre-trade information – including details of their axes, inventories and indicative prices – and some asset managers have built internal systems to archive, organise and analyse this data to improve price discovery.

“On the buy side, you see all the public information the sell side sees, such as Trace. But we also see what every single bank is doing in terms of inventory, price levels, research they send out, what they’re trading, what they’ve traded, and names they’re active in,” says a fixed-income trader at an insurance company in Boston.

New technologies – such as Neptune, a messaging network for pre-trade communication in corporate bond markets, which launched in 2015 – have made it easier for asset managers to aggregate and analyse this information. “That data would traditionally be sent via emails and spreadsheets by dealers to their clients, and we’ve put everything in a standardised protocol and made the process more efficient,” says Grant Wilson, interim chief executive of Neptune.

In recent years, these changes have occurred in parallel with a growing capital burden for banks. Many have retreated from the corporate bond market, further tilting the information advantage in their clients’ favour.

Leveraging all-to-all platforms

The buy side is still figuring out how best to use this information. Some are using it to opportunistically provide liquidity on new all-to-all trading venues for corporate bonds, which allow asset managers to act as price makers or takers.

“[All-to-all trading venues] give you the opportunity to reach other counterparties in the market – namely other buy-side firms – without having to go through a dealer in the traditional sense. We use them more now and we have greater connectivity as a result,” says Anthony Cucinotta, head of trading at Capital Advisors Group in Boston. “At first, we dipped our toes in to see what would happen without disrupting relationships with banks, but now there is greater connectivity and end-user flow, which is critical for these systems to work. The queries and notifications of interest have grown dramatically in the past 12 months.”

MarketAxess saw record volumes of $167 billion in 2016 – up 83% on 2015 – on its all-to-all platform, Open Trading, where non-banks provide nearly 70% of the liquidity.

Asset managers on the platform say they typically beat dealers on price when responding to a request-for-quote. “If we see an offer on MarketAxess – it might be for only half the position – I will bid on it, and a lot of the time I will win, which tells you a lot about where the market is going,” says an asset manager in Boston.

[All-to-all trading venues] give you the opportunity to reach other counterparties in the market – namely other buy-side firms – without having to go through a dealer

Anthony Cucinotta, Capital Advisors Group

The success of Open Trading is fuelling interest in other all-to-all venues. TruMid, a session-based dark pool for credit trading, saw $4 billion of notional volume in the second half of 2016 – more than it achieved in the whole of 2015.

UBS is counting on buy-side price makers to propel volumes on Bond Port, its agency trading platform for corporate bonds. The buy side provided liquidity for half the volume executed on the platform in 2016, compared to around 25% the previous year.

Tradeweb, which ranks as the second-largest venue for trading credit securities after Bloomberg, also plans to launch all-to-all trading in corporate bonds in 2017.

The ability to make prices on bonds is helping some asset managers generate better returns for investors. Jim Switzer, global head of credit trading at Alliance Bernstein, which built a proprietary system to aggregate and analyse price data in the bond markets, says the firm sees transaction cost savings of 4.39 basis points on average when acting as a price maker on Open Trading. “We really generate alpha in our portfolio by being a liquidity provider or price maker, which typically allows us to buy much closer to the bid side and sell much closer to the offer side,” he says.

Some hedge funds are also running arbitrage strategies that seek to earn a return by providing liquidity in corporate bonds, albeit in small size. “We’re quite active in credit markets, earning the bid/offer and providing liquidity in doing so,” says Bill Michaelcheck, founder, chairman and chief investment officer at Mariner Investment Group, a fixed-income hedge fund in New York.

Michaelcheck admits the firm is currently only able to trade individual bonds in relatively small sizes, typically in the $500,000 to $2 million range. The firm also runs a liquidity provision strategy in credit indexes and exchange-traded funds, where individual trades can be in the tens of millions of dollars.

While the buy side is benefiting from these changes, dealers are struggling to adapt to a world where regulations are eroding their ability to act as principal market-makers and trading is shifting to exchange-like venues where clients have an information edge.

The Basel III capital rules have made it costly to maintain large inventories of corporate bonds, while the Volcker rule prohibits US banks from trading for their own accounts. “The capital requirement for holding investment-grade corporate bonds is six times higher than it used to be,” says McVey at MarketAxess. “Banks are holding far less inventory because of those changes.”

Primary dealers’ net holdings of corporate debt securities have fallen from a peak of around $265 billion in 2007 to $12 billion at the end of 2016, according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Over the same period, US open-end bond mutual fund assets have doubled from $1.5 trillion to more than $3 trillion (figure 1).

So, while asset managers have expanded their footprint in the credit markets, dealers are trading less and are no longer privy to the same information flows. This is reflected in volumes in the interdealer markets, which used to be an important source of price discovery for dealers.

“A lot of pre-trade information was sourced through interdealer brokers where there would be a voice dealer sitting between multiple banks,” says a buy-side trader who previously worked at a large dealer. “You would see markets being made to other banks and you would get a sense of positioning, pricing and liquidity.”

Traders naturally go towards bonds that are easier to get in and out of, and that offer a better certainty of an exit price

Laurent Samama, BNP Paribas

That is no longer the case. According to data from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (Sifma), interdealer trades represented roughly 17.5% of average daily volume in corporate bonds in the third quarter of 2016, compared to 50% for US Treasuries. “The interdealer market is not a big part of overall market volume in credit and doesn’t contribute a lot to fair price formation,” says Laurent Samama, head of US credit trading at BNP Paribas in New York.

That puts dealers in a tough position. When banks trade abundantly, they see more of what their clients are doing and gain an information advantage that allows them to stay a step ahead of the market. Regulations have restricted banks’ ability to trade and efficiently price risk. But the same regulations also punish them for getting their pricing wrong.

“If you get it exactly right, you won’t need to hold on to the bond for very long because someone will be there to take it off you,” says a global credit head at a large bank in London. “But if you get it wrong, you’re either losing money or holding on to it for a longer period of time.” And holding bonds for longer ties up scarce capital, which hits the bottom line.

Forcing change on the sell side

Dealers are just starting to get to grips with the problem. “Every bank is trying to do something now,” says the director of fixed income at the asset manager in Boston. “Even regional banks that don’t really use much balance sheet will constantly talk about how they’re trying to improve, aggregate and use information more effectively.”

It’s easier said than done. “One bank I know was trying to get salespeople to type in enquiries they received in order to log buys and sells [so that data] could be cross-referenced,” says the director of fixed income. “But it struggled to get many of the traders to actually change their behaviour.”

Still, most dealers are pressing ahead with efforts to overhaul their data and develop new price discovery mechanisms – although they can be coy about the details. “The industry is very focused on market data and pre-trade information. This is the next generation and evolution of credit trading,” says a credit market structure strategist at a US bank in New York.

Dealers are also trying to exert more control over the data they disseminate to the buy side. In the past, dealers would blast out emails with spreadsheets of bonds held in inventory to potential counterparties and share pre-trade information via instant messages. Now, firms are investing in technology to streamline their communications so they can send relevant information to specific customers.

Today, banks treat us more like a customer than a trading counterparty

Today, banks treat us more like a customer than a trading counterparty

Jim Switzer, Alliance Bernstein

“For us, there is a difference between data that is intended for customers via networks like Algomi or Neptune, which streamline the way information is sent and allows us to analyse that data, and other initiatives where our data is not intended to be forwarded or redistributed to where it is used as a composite and aggregated with other data, which we do not like,” says the global head of market structure.

Chris Bruner, head of US credit product at Tradeweb, says banks are cracking down on the latter. “Banks will be thoughtful about where they distribute data,” he says. “If they’re benefiting from that, then they won’t mind the asymmetry. A lot of the banks are trying to figure out how to target data to where it’s most useful, with a growing number sending information tailored individually to each client.”

Some dealers are also changing the way they treat customers, with a bigger emphasis on building trust and loyalty, rather than treating trading relationships as a zero-sum game. “The sell side has become a lot more client focused. The calls to us now are more ‘what can I do for you?’ or ‘how can I help you today?’ There is more of a focus on what our need is, rather than’‘we need to get rid of these bonds on our balance sheet’,” says Cucinotta at Capital Advisors Group.

Alliance Bernstein’s Switzer has also noted the shift in mentality among dealers. “Today, banks treat us more like a customer than as a trading counterparty,” he says. “Twelve months ago there was an unwillingness on the sell side to embrace change. There was a lot of dragging of feet. But in the last six months it’s been an earth-moving change, as they are willing to acknowledge that part of any liquidity solution will first require greater efficiencies together with a technological solution.”

Maintaining liquidity

Still, a new attitude and better control of pre-trade data will not fix all the problems facing bond dealers. Regulations have forced banks to shrink their holdings and turn over their balance sheets more quickly. As a result, dealers are focusing almost exclusively on the most liquid securities.

“It doesn’t cost more to hold a bond that is less liquid, but I give my traders targets on turnover and holding periods. So traders naturally go towards bonds that are easier to get in and out of, and that offer a better certainty of an exit price,” says Samama at BNP Paribas. “It’s not just about the carry cost, even if those costs structurally impact the amount of bonds held on dealer balance sheets, which in turn changes the liquidity paradigm. It means that when the buy side tries to buy a bond, it might not be held with a bank.”

That is a big concern for buy-side traders. “Risk taking is centered more in the upper 20% of the marketplace, and a lot less in that bottom 80%,” says Switzer. “So you have a very bifurcated market – one that is liquid up top and very illiquid down below.”

That means buy-side traders must work harder to find liquidity in everything but the most commonly traded bonds. Many are taking a two-pronged approach, acting as a price maker on all-to-all venues when the opportunity presents itself, while maintaining strong relationships with dealers that can source liquidity from a web of buy-side clients.

Electronification has helped the buy and sell side be a lot more efficient and effective, and not just when executing

Electronification has helped the buy and sell side be a lot more efficient and effective, and not just when executing

Guy America, JP Morgan

“If you’re a sell-side trader and you have an account that wants to sell a block of interesting illiquid bonds, you can’t just blast that out to the marketplace. You have to make very targeted and thoughtful phone calls, and we are set up to make sure we see these opportunities,” says Switzer. “Our investment process is designed to allow the trading desk to speak to the risk appetite of the firm. When the sell side engages us, they know they will get a very quick answer as well as valuable feedback.”

Even the most sophisticated and well-informed asset managers admit they cannot rely exclusively on electronic all-to-all platforms for liquidity, and few believe that new data sources and trading venues will spell the end of direct relationships with dealers.

“If I come to a bank anonymously on a platform, the trader might be less inclined to give their best level, whereas if you’re a good customer and need a bid for certain bonds, then sometimes I think going direct is the better approach,” says Mike Nappi, a senior credit trader at Eaton Vance in Boston. “The platforms have their place, but the important thing for the buy side is knowing how to use the two simultaneously. A good trader in today’s market knows how to balance those things.”

Shared benefits

That view is shared by some on the sell side, who say electronic trading helps both sides of the market. “Electronification has helped the buy and sell side be a lot more efficient and effective, and not just when executing. It’s now much easier to have a much higher velocity on your balance sheet, and you can be more targeted about offerings that you want to discuss with clients. Also, it is now far easier to store and analyse large amounts of information to make better judgement calls on prices,” says Guy America, co-head of spread markets at JP Morgan in London.

Indeed, buy-side firms still value their relationships with top dealers that can operate effectively in both the electronic and voice markets, and they are rooting for them to succeed. The asset managers that spoke to Risk.net for this article say they never consciously use their information edge to trade against their dealers, and would like to see better price discovery mechanisms on the sell side. “Imagine how much more efficient the market would be if everyone on the sell side had the same level playing field in terms of price information [as the buy side],” says the fixed-income trader at the insurance company in Boston. “They could spend so much more time trying to figure out how to position risk, as opposed to figuring out a level.”

Some on the sell side say their firms are already starting to get there. “We still see ourselves as a principal market-maker,” says the global head of market structure at a bank in New York. “We have become a lot better at turning over our balance sheet, at having a better sense of where and how to get out of risk – not just one bond for another, but risk transformation, up and down a curve, and cash versus derivatives, for example. So we use all those tools to transform risk, along with evolving to use better systems and data tools internally.”