Negative Rates are No More, But The Era of Big Central Banks Reigns Supreme

Introduction

The Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) meeting last month was perhaps the most consequential central bank meeting of the entire year. The BOJ raised interest rates by 10 bps to 0-0.10%, all-in-all a small amount in magnitude. However, this marked the first interest rate increase by the central bank in 17 years. Moreover, it marked an official departure from a negative interest rate policy, which the bank had been engaged in since 2016.

In addition to the exit from negative rates, the Bank of Japan also dropped its target for long-term interest rates. Under its policy of Yield Curve Control (YCC) the bank had been targeting a level of long-term interest rates to add further monetary stimulus beyond lowering the short-term rate. The YCC had been initiated to peg Japanese government bond yields to 0% but had been relaxed in recent months as economic conditions in Japan became more consistent with a tolerance for higher rates. The move to end YCC was thus not unexpected, but still signals a significant loosening of the monetary reigns from the BOJ.

The BOJ’s actions serve as an illustration of two trends happenings in central banking:

- A move away from negative interest rates.

- A general reduction in central bank balance sheets.

The former is a trend that looks likely to persist, whereas the latter is purely a temporary phenomenon.

1. The End of Negative Interest Rates

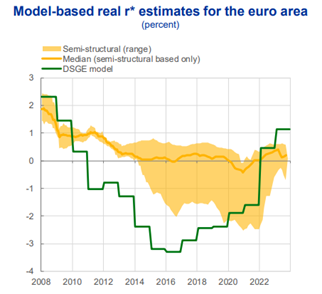

The BOJ’s rate increase marks the end of the negative interest rate era, which began in Denmark in 2012 and lasted for a period of 12 years in total. This trend would seem to be a durable one, as economies across the G20 have fared well in the face of a substantial rise in interest rates. Indeed, as we mentioned in our blog “Where is the Neutral Rate”, there’s some evidence that the neutral interest rate (“r*”) in the U.S. is on the rise. The same can be said for Europe, where estimates of r* are also increasing.

Figure 1: European Central Bank

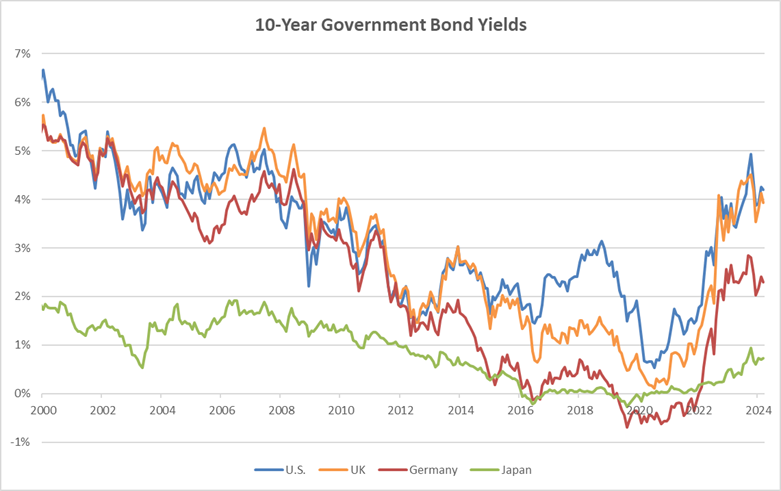

Much of this hinges on the fact that major economies are no longer suffering from persistent shortfalls in demand. The post-pandemic period released a wave of pent-up consumer spending, large-scale fiscal stimulus, and economic change that has resulted in a combination of above trend growth, healthy labor markets, and high inflation. All of these are consistent with structurally strong demand, which in turn supports higher interest rates. Contrast this to before the pandemic, when central banks were regularly missing their inflation targets on the downside. This coincided with a period of continual decline in rates.

Figure 2: Bloomberg

This brings us to the efficacy of negative interest rates. The debate over their effectiveness is far from settled, in large part because the counterfactual of never having implemented them is unknowable. It should be noted, however, that economies that employed negative rates didn’t necessarily perform any better (or see any more material boost in lending) than countries that chose not to employ them. Indeed, it seems clear that both the fears and hopes of negative rates at their onset were probably overblown. Money market funds continued to survive in Europe despite the ECB’s deposit rate reaching -0.50%, and a boom in speculative lending didn’t necessarily manifest.

In a report from 2021, the IMF suggests that negative rates had a positive impact on financial conditions, “without raising significant financial stability concerns.” Of course, opinions will vary wildly, perhaps best illustrated by Bleakley Advisory Group CIO Peter Boockvar’s quote that they were “the dumbest idea in the history of economics”. But the bottom line is that the days of negative interest rate policy now seem to be firmly in the rear-view mirror.

2. Central Bank Intervention is Well and Alive

In contrast, the move by the BOJ to drop YCC is not indicative of a trend towards less central bank intervention. For one, the BOJ is not even adjusting the amount of Japanese government bonds its purchasing on a rolling basis. To do so would be impractical, as it is far and away the largest buyer in the market.

Figure 3: Figure taken from Robin Brooks’ (Brookings Institute) Twitter: https://twitter.com/robin_j_brooks/status/1770809180707811663

This dynamic, in which the central bank is a larger scale buyer of domestic government debt, is widespread across the large central banks. As central bank balance sheets exploded following the financial crisis, they took on a greater and greater share of their respective government’s debt. This had the effect of increasing liquidity in the financial system, in the form of excess reserves to banks. This is a topic we’ve covered many times in the past, including in our recent whitepaper Quantitative Tightening (QT) is Coming to An End – What Does it Mean to Cash Investors?

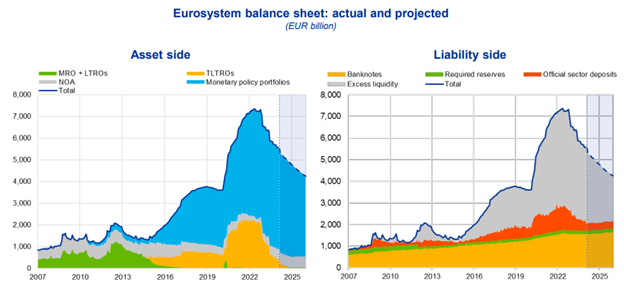

For the purposes of this piece, the main takeaway is that the consensus amongst central bankers is that having lots of excess liquidity in the banking system (and thereby a big foothold in the market) is the prudent thing to do. Currently, major central banks including the Fed, ECB, and BOE are engaged in Quantitative Tightening, whereby they are reducing the size of their balance sheets. However, they plan on keeping large amounts of reserves in the system rather than returning to the scarce reserve operating systems seen before the Financial Crisis during which there were essentially no excess reserve balances. This means that wherever the stopping point, their respective balance sheets will likely remain much larger than pre-Financial Crisis levels.

The ECB’s internal projections for its balance sheet lay out this dynamic quite well. The ECB expects its balance sheet to contract from a peak of ~€7T to ~€4T by the end of 2025, however at this point its balance sheet would be ~3x its 2010 level. Even accounting for growth in currency notes and non-reserve deposits, the end point would be a balance sheet at least twice as large as it would be under a scarce reserve system.

Figure 4: European Central Bank

The same logic extends to exotic central bank lending programs. Whether it be the Bank Term-Funding Program in the U.S. or Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations in Europe, the trend is towards more and more lending facilities. For these programs, once the cat is out of the bag, there’s no putting it back in. They immediately become part of the central bank toolkit, ready to be whipped out at the first sign of trouble.

Overriding the elevated balance sheets and the emergency lending programs is the principle of financial stability. Ultimately, in times of crisis having the ability to extend liquidity to those that need it is a valuable tool in stemming contagion. However, this has essentially overridden every other principle whose costs are more diffuse. There is value to having an active intra-bank lending market, for instance, as it allows for price discovery and forces banks to actively monitor each other’s health. And with more and more central bank intervention comes greater concern over moral hazard. Nevertheless, the die has been cast. Negative rates are a thing of the past, but the era of big central banks is well and alive.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.