Deposit Betas Rising but Still Falling Short

Abstract

Deposit rates are starting to increase as we move further into a rising rate environment. Banks still have not rewarded depositors sufficiently with a 21% average deposit beta, although some executives expressed moving it above 50%. The wait for higher rates continues unless depositors are willing to consider market-based instruments. There, several options exist to suit their liquidity and credit situations.

Introduction

After almost a decade of near-zero investment returns, liquidity investors are beginning to reap the benefits of higher rates. This is true for investments in capital markets, where rates have risen along with the Federal Reserve’s actions. On the other hand, depositors may need to wait a bit longer — a lot longer if banks have their way.

We wrote last August about how deposit rates have failed to keep pace with rising short-term interest rates. The benchmark fed funds rate has risen another 50 basis points (bps, or 0.50%) since then, while the national average money market account (MMA) rate has increased just 5 bps. This results in a “deposit beta” of 10% (change in deposit rate over change in benchmark rate) for the period.

While deposit betas have been stubbornly low in recent quarters, all hopes are not lost. Transcripts from recent earnings calls at several of the largest regional banks indicate that betas may move materially higher soon. In this month’s report, we provide another update on the state of deposit rates, with a sample of deposit betas among major US banks. Additionally, we end with a suggestion for liquidity investors to look to capital markets for yield opportunity.

Growing Deposit and Reserve Balances after the Financial Crisis

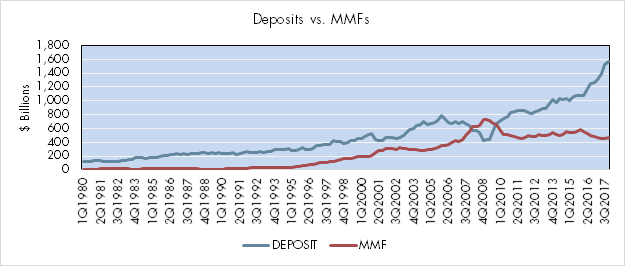

Businesses have used deposit accounts to manage liquidity for as long as the modern banking system has existed. Starting in the mid-1990s, money market mutual funds (MMFs) gained popularity among institutional liquidity accounts as a preferred cash management tool. For a brief period around the 2008 financial crisis, MMF balances surpassed deposits. The crisis and ensuing regulatory issues resulted in stagnant MMF balances while deposits surged (Figure 1). At the end of 2017, total deposit and currency balances at “nonfinancial corporate businesses” stood at $1.5 trillion, while MMF shares held by the same entities totaled $472 billion, for a ratio of roughly 3:1.

Figure 1: Liquid Balances at Non-Financial Corporate Businesses

Source: The Federal Reserve’s FRED database quarterly ending 4Q2017

Higher deposits immediately after the financial crisis were attributed to the extraordinary government measure of deposit guarantees. Regulatory scrutiny into MMFs in later years left major institutions with few alternatives other than deposits for liquidity management.

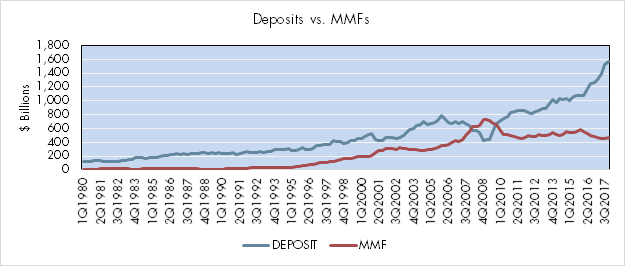

During the same period, banks benefited from ample liquidity thanks to large reserve balances at the Federal Reserve. Figure 2 shows the growth of reserves over the last decade. At the end of 2007, total reserves stood at a mere $8 billion, 78% of which were required balances. Reserves ballooned after several rounds of asset purchases by the Fed, peaking in 2014 before declining to a still historically elevated level of $2 trillion at the end of 2017. As Figure 2 indicates, almost all the balances represent excess liquidity beyond what they need to fund their operations.

Figure 2: Total vs. Required Reserves at the Federal Reserve

Source: The Federal Reserve’s FRED database monthly ending April 2018.

With interest rates close to zero, yield was not a primary concern for liquidity investors as they parked cash in deposit accounts. Banks also had no incentive to pay up thanks to large reserve balances. After the Fed started increasing rates in December 2015 and tapering reinvestments to shrink reserves from July 2017, it was expected that deposit rates would respond accordingly.

Deposit Rates Are Not Keeping Pace with Yield Increases

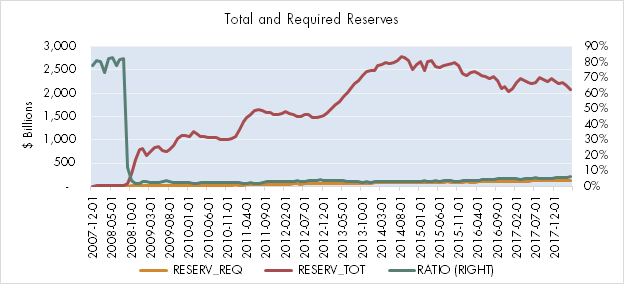

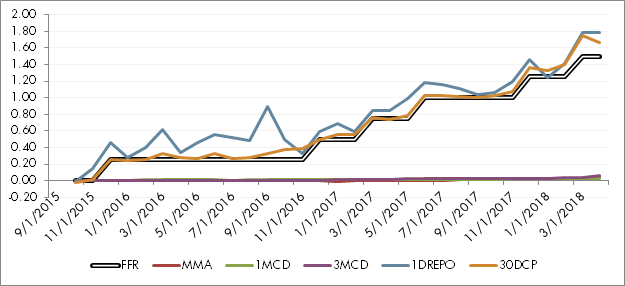

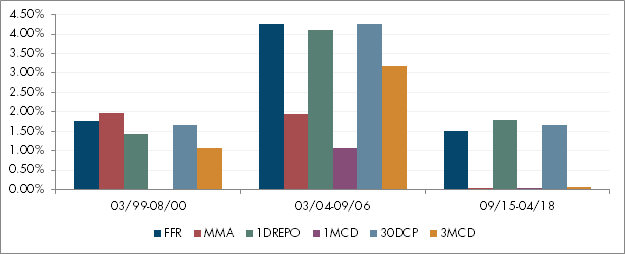

Through March 2018, the Fed hiked rates six times at 0.25% increments. Short-term market rates climbed in response, but bank rates have yet to see meaningful increases.

Figure 3 provides a snapshot of short-term rates in recent years. The bottom range of the fed funds rate (FFR) rose from 0.00% to 1.50% between December 2015 and March 2018. The overnight repurchase agreement (repo) rate tracked by Bloomberg rose 1.79%, and the 30-day A1/P1-rated commercial paper (30DCP) index rate rose 1.65%, outpacing the Fed’s rate increases. Stated differently, the betas for the 1DREPO and 30DCP through April 2018 were 119% and 110%, respectively.

By contrast, national average deposit rates published by the FDIC have hardly budged. Among jumbo deposits (greater than $100,000), the money market rate (MMR) has risen only 0.05% to 0.17% since December 2015. The one-month certificate of deposit rate (1MCD) rose 0.03% to 0.09% and the three-month CD rate (3MCD) rose 0.06% to 0.15% over the same time period. Their respective deposit betas were 3%, 2%, and 4%.

Figure 3: Comparative Short-term Interest Rates

Source: FDIC’s weekly national rates and Bloomberg

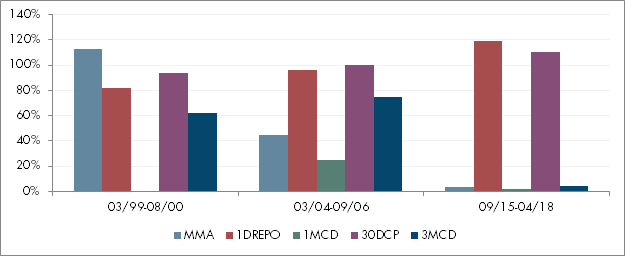

A comparison to the two previous Fed tightening cycles (June 1999–May 2000 and June 2004–June 2006) indicates that banks today are less willing to pay up on deposits.

Figure 4: Changes in Select Short-term Interest Rates

Source: Bankrate.com and Bloomberg

Figure 5: Beta Relative to Fed Funds Rate

Source: Bankrate.com and Bloomberg

Figures 4 and 5 present the changes in select short-term rates alongside the FFR during the three rising cycles, from three months before the first hike to three months after the last one. Due to the lack of historical data on FDIC national average rates, we used Bankrate.com’s respective indices.

Figure 4 shows changes for three deposit rates (MMA, 1MCD and 3MCD), and two market-based rates (1DREPO and 30DCP). Figure 5 shows their changes relative to the changes in the FFR.

- 03/99-08/00: Figure 5 shows that MMA was the best performing instrument during this cycle, rising 113% relative to FFR increases. This was followed by 30DCP, which rose by 94% of FFR increases. Overnight repo and 3MCD rose 82% and 62%, respectively, relative to the FFR.

- 03/04-09/06: In this period, 30DCP was the best performer, matching (+100%) FFR increases, followed by 1DREPO, which matched 96% of FFR increases. 3MCD, MMA and 1MCD rose 75%, 45% and 25% of the FFR, respectively.

- 09/15-04/18: In the current period, 1DREPO rose 119% of FFR increases, followed by 30DCP which rose 110% of FFR increases. 3MCD, MMA, and 1MCD have hardly moved, rising 3%, 2% and 4% of FFR, respectively.

To conclude, despite the 1.50% rise in the fed funds rate over the last 28 months, money market and short-term CD rates have barely budged. Historically, these rates tended to rise with the policy rate, sometimes exceeding benchmark increases. In contrast, short-term market-based rates rose along with FFR in all three periods by about the same magnitude.

Possible Causes for Low Deposit Rates

In our August 2017 research piece, we discussed several possible causes for banks’ muted reaction to rate increases in this current cycle. We reproduce the summary in bullet form:

- Abundant reserves: Banks have more deposits than they need.

- Restrictive regulations: The costs of holding deposits have increased.

- Banks keeping the first cut: Banks want to pay themselves before depositors.

- Investor inertia: They have not adjusted expectations after a long period of yield drought.

- MMF reform: A natural market-based substitute is not as attractive now.

Hopes for Higher Rates

Are higher deposit rates in sight? Are banks simply delaying an increase or will they pay below-market rates on deposits permanently?

Based on information obtained from bank executives and investors, we expect banks to raise deposit rates more rapidly this year, although the increases are likely to remain less competitive than market rates until reserves are drained sufficiently, and lending picks up substantially. We were able to get some confirmation of this from transcripts of senior bank executives at first quarter 2018 earnings conferences.

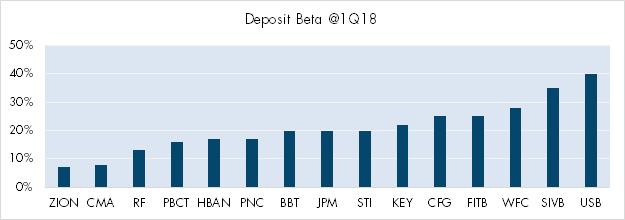

Figure 5: Beta Relative to Fed Funds Rate

Source: From 1st quarter 2018 earnings call transcripts S&P 500 banks, Bloomberg

Figure 6 gathers estimated deposit betas disclosed by executives at 15 banks in the S&P 500 Index. Data from three other banks in the sub-index is undisclosed thus unavailable. While there can be different betas thanks to different loan mixes and deposit terms, this aggregate level distribution provides helpful insight.

The average beta is at 21% in the first quarter 2018, most of which have increased from the previous quarter and/or the year-ago quarter. They range from 7% for Zion Bank to 40% for US Bank. Most executives project higher betas in the next quarter and through the end of the year, some placing the figure at above 50%. None projected the ratio to rise close to 100%.

It is interesting to note that, to preserve net interest margins (NIMs), bank executives stressed their reluctance to expand deposit betas. In a narrow sense, deposit beta is a zero-sum game between banks and depositors.

Conclusion: Low Beta Deposits vs. Market-based Options

It is undisputable that banks have not rewarded their depositors sufficiently as rates move higher. With improved profitability, friendlier regulatory treatment of deposits and a smaller Fed balance sheet, one would expect demand for deposits to rise, which would in turn lead to higher betas. Both anecdotal and empirical evidence point to the validity of this line of thinking.

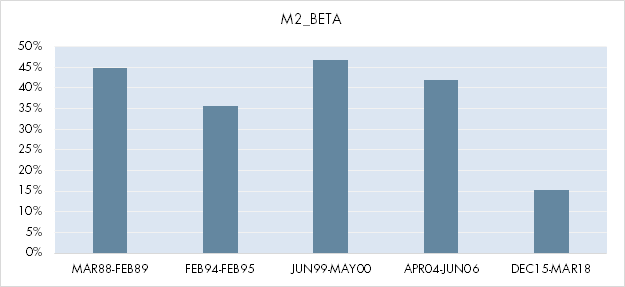

However, as shown in Figure 7, deposit betas in the current cycle have a long way to climb to reach their historical averages. For a longer historical perspective, we use the M2 Own rate to capture deposit betas in the last five rising rate cycles.

Figure 7: M2 Own Rate Beta in Rising Interest Rate Cycles

Source: The Federal Reserve’s FRED database monthly ending April 2018.

In monetary policy parlance, M2 is a broader classification of money than M1 and includes highly liquid near-cash assets. The M2 Own rate is the weighted average of rates received on all interest-bearing assets in the Federal Reserve system.

Figure 7 shows the aggregate M2 beta today at 15%. This compares to the average of 42% for the last four cycles. It is doubtful that the figure will catch up to the historical average now that we are probably more than half way through the rate cycle.

As we showed in Figures 3-5, rates on short-term instruments such as CP and repo have kept up pace with the Fed, though. Therefore, it is advisable for investors sensitive to the income gap to investigate market-based strategies such as direct purchases and separately managed accounts. Ultra-short bond funds may also be an option, although shared liquidity and tax implications from NAV volatility may deter some investors.

We cannot end this commentary without addressing the credit risk associated with deposits. In the institutional context, most deposit balances are in excess of the FDIC’s deposit insurance level. Thus, investors must evaluate the risk of being exposed to a limited number of bank counterparties versus a diversified portfolio of names with similar credit characteristics, or even non-bank corporate credits.

In short, depositors may need to wait a while longer for materially higher rates unless they are willing to consider market-based instruments. There, several options may exist to suit their liquidity and credit needs.

DOWNLOAD FULL REPORT

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.