Brexit: An Overview

Abstract

With the March 29th deadline for the UK to leave the European Union looming, there is still no decision about how the departure will be managed. In the two years since a referendum forced the UK government to trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty indicating their intention to leave the EU, negotiations over a deal for a smooth exit have been unsuccessful. The two sides now are on the precipice of having to extend the deadline past March 29th to avoid a no-deal Brexit. What started out as a contentious process has turned into an administrative nightmare, with no definitive end in sight.

The goal of this piece is to take readers through the many recent developments surrounding Brexit, which have shifted daily, as well as attempt to gauge the highly uncertain outcome from a political and economic perspective. Lastly, we review some of the sector specific consequences of Brexit while trying to qualify the possible outcomes most deserving of investors’ attention.

Summary of Events

Here is a summary of how Brexit has unfolded:

- In 2016, then Prime Minister David Cameron gave into public pressure to hold a referendum on whether to maintain the UK’s status as a member of the EU. The vote, held on June 23rd, 2016, shocked the world, with “Leave” winning by a margin of 52-48%. In the wake of the vote, Cameron resigned and was replaced by current PM Theresa May.

- On March 29th, 2017, May followed through on her promise to honor the Brexit vote by triggering Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. This marked the start of a two-year timeframe for the UK to leave the EU.

- Since then, negotiations have focused on a withdrawal agreement, which outlines a general framework for the UK’s post-Brexit relationship with the EU. It would determine, amongst other things, the rights of EU citizens living in the UK, the size of a onetime Leave payout from the UK to the EU, and their broad-scale economic relationship.

- In November 2018, Theresa May’s government and European leaders reached a withdrawal agreement. The deal, however, proved to be an unmitigated disaster for May. She faced open revolt within her cabinet, with Brexit Secretary Dominic Raab resigning in protest upon its release. Furthermore, it was overwhelmingly rejected in Parliament. The deal failed by a margin of 230 votes, something unheard of in the UK’s parliamentary system. Following the vote, pro-Brexit members of the Conservative Tory party brought a no-confidence vote against May, which she survived by a hair.

So where does this leave things? The government has a deal with the EU, but barring major revisions, it remains unpalatable to Parliament. Publicly, EU leaders have refused to re-enter talks, insisting that after two years of negotiations the deal is what it is. Privately, there seems to be some willingness to reconsider this stance in the wake of discouraging performance results out of the German, French, and Italian economies. Nevertheless, EU officials are reluctant to grant further concessions to May’s government without assurances that she would be able to pass a revised deal through Parliament.

Given the lack of movement, a delay in the proceedings now seems all but inevitable. In early March, May announced she would bring forward a vote in Parliament to request an extension of the deadline. May had previously expressed opposition to such a move, however following a second defeat of her negotiated deal, as well as a rejection of a no-deal Brexit, she had little choice but to acquiesce1. As expected, the extension request was approved by Parliament on March 14th. It will next be proposed by May at the upcoming EU summit on March 20th-21st, where it will require unanimous approval by EU nations.

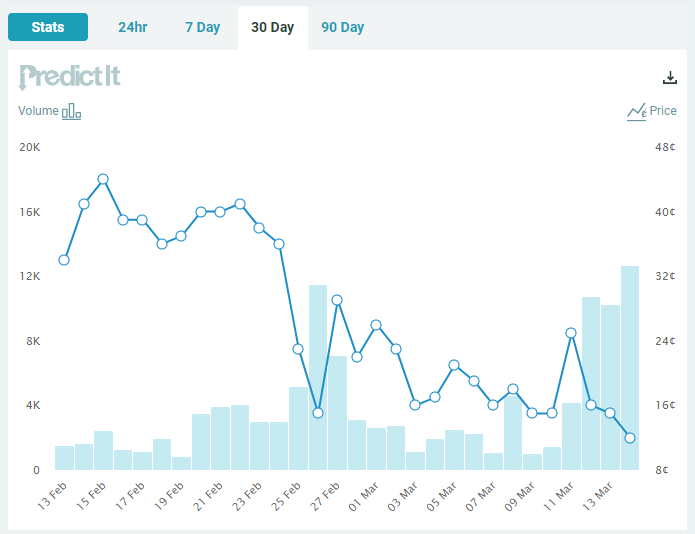

There remains some uncertainty as to how long an extension would be, and for what purpose. French President Emmanuel Macron emphasized that Britain would need to have a clear plan on how to resolve the issue of Brexit, stating that “under no circumstances would we accept an extension without a clear perspective.” However, the majority of other European leaders, including German Chancellor Angela Merkel, have taken a softer stance in hopes of avoiding a mutually disadvantageous no-deal outcome. European Council President Donald Tusk noted that a delay is the “rational solution” and that the EU would be “understanding.” Thus, it seems likely that the proposed extension will be accepted. Betting markets are already reflecting this; odds of a March 29th exit on the popular site PredictIt plummeted in the wake of the vote.

Figure 1: PredictIt Implied Odds of the UK Leaving EU on March 29th

Source: PredictIt, Will the United Kingdom officially exit the European Union by March 29?

Looking Forward

Assuming the extension is approved, all options will remain on the table. The UK government could opt to re-open negotiations, call for a second referendum, or call a general parliamentary election, just to name a few. The possibilities are nearly endless.

Ultimately however, Brexit will end in one of three discrete outcomes: with the UK staying in the EU, with a negotiated exit, or with a no-deal exit. Staying in the EU remains the least likely scenario, despite growing public support for a second referendum and the recent endorsement of one by opposition Labour Party Leader Jeremy Corbyn. There are a number of reasons for this, chief of which is that the majority Tory party and the Prime Minister oppose it. Furthermore, the politics and logistics of a second referendum are tricky. A second referendum is a direct admission that democracy failed the first time around, be it due to lies from pro-Brexit politicians or sheer voter ignorance.

The question of what to put on the ballot is also a tricky one. Another straight up-or-down vote on Brexit is out of the question, and a vote that includes only the government’s deal could isolate those in favor of a harder Brexit. As such, it seems that a second vote would necessitate all three options being on the table. This poses its own set of challenges. In short, the chances of a second referendum, and with it the possibility of the UK staying in the EU, remain slim.

This results in a choice between a negotiated deal or no deal. Nearly all parties involved agree that coming to the table is preferable. Nevertheless, a negotiated deal is far from certain at this point. This is largely due to contentions over the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland.

At the moment, there is effectively no border between the two countries, and thus no border between the UK and the EU. Should the UK leave the EU, this would no longer be viable. The free movement of goods and labor would end, requiring some sort of “checkpoint” between the two.

The most straight-forward solution would be to institute a physical border between Northern Ireland and Ireland. However, given their desire to maintain a close relationship, this has been effectively ruled out. The Irish government is adamant that a hard border would be a violation of the Good Friday Agreement2, and the UK is averse to any arrangement which could aggravate tensions between the two jurisdictions.

Reconciling the inherent tension between the UK’s desire to leave the single market while also upholding the Good Friday Agreement has proved to be difficult. Various Members of Parliament (MPs) have issued proposals for “alternative arrangements” at the border, but these are generally quite vague and involve the use of technology that is not readily available. Another option is to have Northern Ireland remain in the customs union, effectively using the Irish Channel as the border checkpoint for goods traveling into the UK. However, this is unpopular with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP)3, the majority party in Northern Ireland, which views such an arrangement as a slippery slope leading to the potential reunification of Ireland.

The lack of viable alternatives is what lead the UK government and the EU to its current compromise, referred to as the “Irish Backstop.” The backstop is essentially a delay in instituting a border plan until a workable solution for the border is found. The plan would keep the free movement of goods between the two countries in place, while also allowing the UK to move forward with the next phases of Brexit, namely negotiating new trade agreements. This transition phase, where the UK would effectively remain in the EU, would extend up until December 2020.

This compromise proved to be hugely unpopular amongst British politicians, who accused May of giving in to the demands of the EU. Those on the right viewed it as a backdoor agreement that could keep the UK in the EU indefinitely, should no permanent solution to the border situation be found. Those on the left saw it as the worst of both worlds, combining an eventual hard Brexit over the medium term with a reduction in UK sovereignty in the near term.

Nonetheless, as the deadline approaches, the backstop is starting to look like the only way forward. The EU has held firm on its position that the backstop is, as chief EU negotiator Michel Barnier put it, the “only operational solution to address the Irish border issue today.” Furthermore, as public opinion on Brexit has begun to shift, some on the far-right have conceded it may be the only option. Notably, Jacob Rees-Mogg, head of the far-right, pro-Brexit coalition within the Conservative Party known as the European Research Group, dropped his condition that the backstop would need to be scrapped in order to gain his support. Even so, the border issue, and with it the entirety of Brexit, remains far from settled.

Economics

This section will focus mainly on the potential impacts of Brexit on the UK and EU economies. However, we should first note that the optimal scenario from an economic perspective is one where the UK remains in the EU. The specter of Brexit has already taken a large toll on the UK economy. According to the Bank of England, studies assessing the impact of Brexit to date estimate that GDP is about 2% lower than it would have been if the UK had voted to remain. This may not sound like a lot, but as economist Simon Wren-Lewis pointed out, this translates to around ₤2,000 per household.

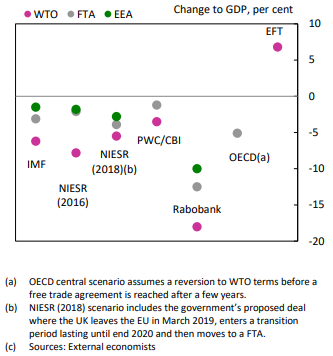

Should the UK go through with Brexit, the impact will only deepen. Forecasts on the long-run impact of Brexit are nearly universal in finding that it will make the UK economy worse off4.

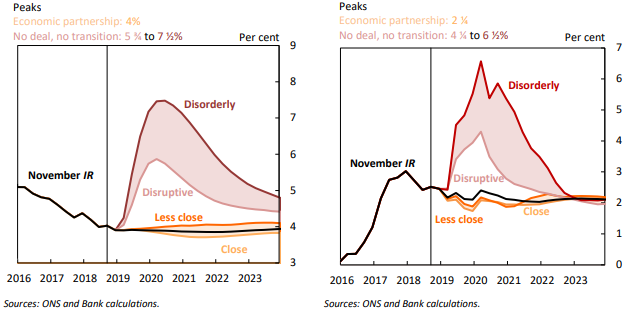

Figure 2: Long-run Estimates of the Impact Associated with Brexit, Relative to Remaining in the EU

Source: Bank of England, November 2018, EU withdrawal scenarios and monetary and financial stability

The reasons for this are clear and straightforward. Brexit reduces the UK economy’s potential growth capacity by reducing its openness to trade, implementing tariffs and instituting barriers to investment. Numerous studies have shown that all three of these factors are correlated with long-run growth potential, as they feed into the ability of an economy to allocate capital efficiently and thereby enhance its productivity. In essence, Brexit, at its core, is a classic supply-side shock.

While determining the direction of Brexit’s impact on the economy is relatively straightforward, measuring its intensity is an inexact science. Generally speaking, the closer the UK is aligned to the EU, the better the forecasted outcome. As a result, a scenario where the UK opts for a Scandinavian style agreement, which would keep it within Europe’s free trade zone, is more optimal than one where it reverts to something akin to World Trade Organization rules5. Still, the degree to which these economic outcomes differ is difficult to ascertain.

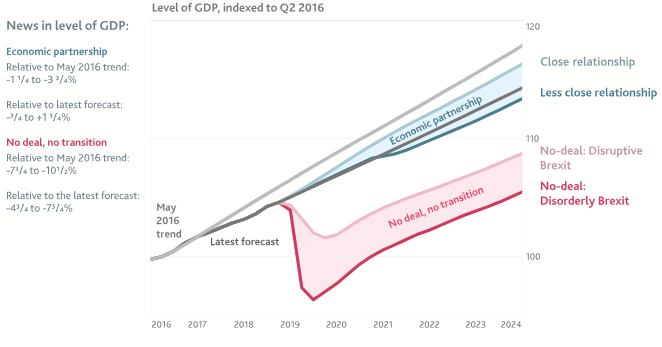

Figure 3 illustrates this point. It displays a range of post-Brexit outcomes the Bank of England (BOE) simulated under four different Leave scenarios. Crucially, this is not an exhaustive list, nor is it a forecast. Instead it is better viewed as an examination of both the best and worst-case Leave scenarios. The May 2016 line provides some context, as it is the bank’s projection for economic growth prior to the Brexit vote, while the Latest Forecast is from this past November (when this report was released).

Figure 3: Modelled Scenarios Based on Different Assumptions About Brexit

Source: Bank of England, November 2018, EU withdrawal scenarios and monetary and financial stability

The “Close and Less Close Relationship” scenarios illustrate that a negotiated Brexit in which the UK retains strong ties with the EU is a manageable outcome. Indeed, it is currently more or less the BOE’s baseline scenario. For some context, the BOE’s assumptions for the “Close and Less Close Relationship” scenarios include the following:

- No tariffs instituted between the UK and EU

- Customs checks/non-tariff barriers either not instituted or implemented after 2021

- UK retains existing EU negotiated trade deals with non-EU countries until at least 2023

- Transition period provides sufficient time for individual sectors to adapt to new rules/regulations

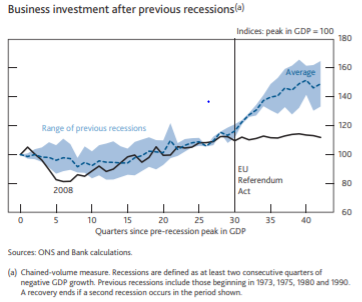

Under this range of scenarios, the most adverse outcome would be that GDP declines by 0.75% relative to the baseline6. On the other hand, the most favorable outcome would find the economy outperforming the baseline by nearly 2%. The rationale behind this goes hand in hand with the economy’s underperformance since the Brexit vote. More specifically, as uncertainty with regards to Brexit has increased, business investment has plunged. Over the past year, business investment within the UK declined by 0.9%, the most since the Financial Crisis. A recent study done by the London School of Economics found that a significant portion of this investment has been redirected to EU countries instead7. This has resulted in the UK’s share of EU foreign direct investment falling from 25% in 2015 to 18% as of late 2017 (it’s likely worsened since then). Another BOE graphic helps illustrate the impact of this.

Figure 4: The Recovery in Business Investment Has Stalled Since the EU Referendum

Source: Bank of England, February 2019, Inflation Report

The recovery in the economy assumes that a portion of that investment will return to the UK as uncertainty eases. The transition period is key in this regard, as the BOE assumes that once businesses have some clarity and a time period to adapt to their new operating environment, they would be more willing to restart projects and expand operations. Outside of this recovery in business investment, the bank also assumes that the British pound would appreciate, which would put downward pressure on inflation and thereby boost real consumer spending. The combination of the two would unleash pent up demand and push GDP growth above the baseline projection. It would also act to keep unemployment, which is largely driven by demand side factors, at its current low level.

Capital Economics’ central projections8 for Brexit largely mirror the central bank’s projections in this scenario, with the additional assumptions that fiscal policy will turn supportive, and financial conditions will ease. As such, they estimate that GDP growth would rise from its current level of 1.3% to 2% in 2019/2020. At the same time, they also assume that the BOE will raise its policy rate from its current level of 0.75% to 2.00%. Relaxing this assumption, the recovery in the demand side of the economy could be even greater.

It should be noted that this is not exhaustive of all potential negotiated Brexit settlements. A harder Brexit could result in the economy underperforming the estimates provided by both the BOE and Capital Economics. Nevertheless, the stability provided by having some agreed upon framework in place is invaluable. This is illustrated by the BOE’s “Disruptive and Disorderly” scenarios (which can be seen in the same graph above). These “worst-case” scenarios assume that, amongst other things:

- Tariffs and custom checks are instituted, and trading terms revert to WTO rules

- Mutual recognitions of work certifications are lost, and financial services firms lose their ability to operate freely between the UK and EU

- There is no transition period, changes are implemented overnight

- The UK loses existing trade deals it had via the EU

- No new trade deals are implemented within the five-year window

The results are disastrous for the UK economy. Under a “Disorderly Brexit,” the BOE estimates that the UK’s economy would contract by close to 8%. This would be an almost unprecedented shock for the UK, magnitudes greater than what they experienced at the depths of the financial crisis. Perhaps even more alarmingly, the output gap would not be projected to close within the next five years, leaving the UK on a permanently lower growth track.

“Close Relationship” vs. “Disorderly” Scenarios

The key differentiators between the “Close Relationship” and “Disorderly” scenarios are the institution of custom checks and the lack of a transition period. Should the UK leave the EU without a deal, wholesale changes to trade policy could happen overnight. Given the lack of contingency planning on the part of the UK, this has the potential to lead to a “sudden stop” in the movement of imported goods. The BOE’s “Disorderly” scenario assumes that UK trade falls by 15% in the short run until new border infrastructure and processes are put into place. This would have an enormous impact throughout the supply chain, resulting in a backlog of trucks at the border, disrupting production lines, and leading to a shortage of imported goods.

The projected downside risks stem from this potential outcome. The negative shock to trade comes on top of tariff barriers, which in turn flow through to lower trade levels and less investment. All of this puts downward pressure on productivity and economic growth. Furthermore, the tariffs and shortage of imported goods would put upward pressure on inflation, which is already above the BOE’s targeted 2% level. This rise in inflation would in turn inhibit the central bank’s ability to respond by lowering interest rates.

Similarly, aggregate demand would be negatively impacted by a combination of rising uncertainty and tightening financial conditions. The BOE believes that consumer spending would decline due to lower expectations of future income and a further decline in the value of the pound. Combined with lower business investment, this would lead to an outright recession and a jump in unemployment (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Unemployment in EU Withdrawal Scenarios (Left); Inflation in EU Withdrawal Scenarios (Right)

Source: Bank of England, November 2018, EU withdrawal scenarios and monetary and financial stability

To be sure, this is on the fringe of potential outcomes. Most estimates of the potential economic impact pale in comparison to this “Disorderly” scenario9. Capital Economics’ own disruptive scenario estimates that it would result in a 3% hit to GDP, while the IMF projects that it would be anywhere from 3-5% worse than in a negotiated settlement.

Some of this divergence is due to exogenous factors, such as the response of fiscal and monetary policy. However, it is in large part linked to assumptions about disruption at the border. The BOE’s scenario assumes that backlogs at the border would continue for an indefinite period. In a country as advanced as the UK, with a relatively competent bureaucracy and high administrative capacity, this seems unlikely. Over time it would be expected that the UK government would put into place the people and infrastructure necessary to relieve bottlenecks at ports of entry. Furthermore, even if the UK was for some reason unable to do this, it could simply give informal orders to let goods in without checks (as is the case now). In either scenario, a portion of the initial lost output would be recovered, resulting in a slightly less disastrous outcome.

Impacts Outside the UK

Outside of the UK, negative impacts could be felt via trade and/or financial markets. A no-deal Brexit would likely result in a global deterioration in risk sentiment, with investors fleeing to safe haven investments. Treasury rates would likely fall, and the dollar would likely appreciate against the pound and the euro. On the other hand, spreads would likely widen across the board, which could have a negative impact on credit availability.

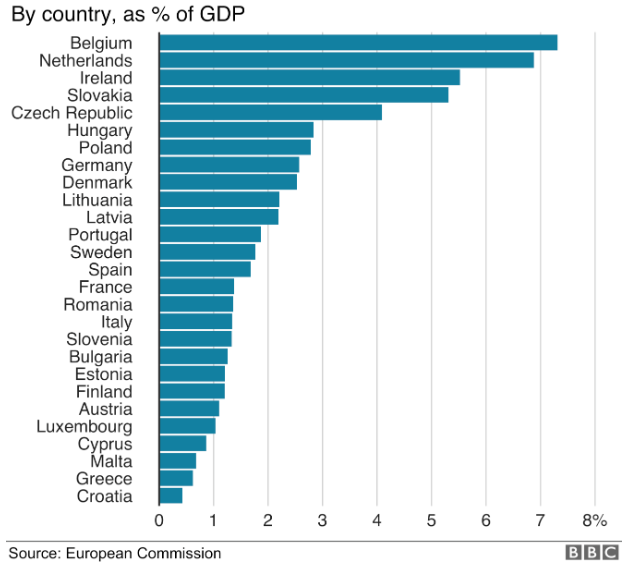

For the EU, a recession in the UK has the potential to spill over into their own economies. As Figure 6 shows, a number of EU nations rely on the UK for a significant portion of their total output.

Figure 6: Exports of Goods to the UK

Source: BBC, Andrew Walker, December 23, 2018, Does the EU need us more than we need them?

For countries such as Belgium, the Netherlands, and Ireland, a reduction in UK demand for imported goods combined with a depreciation of the pound against the euro could potentially have a significant negative impact on their economies. This is especially true given the limited scope for the ECB to further lower interest rates. Overall, the IMF estimates that under a no-deal Brexit10 cumulative EU output would fall by 1.5% and unemployment would rise by 0.7%.

Sector Impacts

While Brexit will be negative for the entire UK economy, the impact will vary by sector. In general, there are five ways in which individual sectors of the economy could be affected:

- Direct export exposure

- Intermediary import exposure/supply chain integration

- Shift in capital investment

- Weaker domestic conditions

- Labor demand

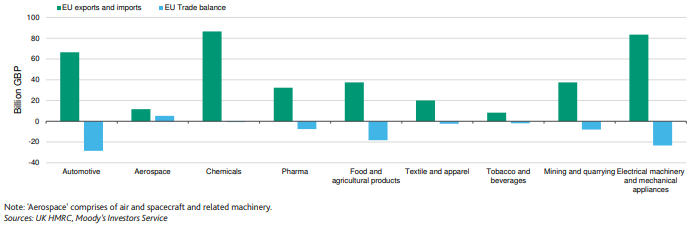

These factors are intertwined to a significant degree; e.g. at the margin, investment in the UK will shift from export sectors of the economy to import sectors post-Brexit. Nevertheless, it still makes sense to analyze these factors individually. Figure 7 displays a selection of industries which have noteworthy import/export exposure to the EU.

Figure 7: UK Industry Trade Flows to EU

Source: Moody’s, Probability of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit has risen, and would be negative for an array of issuers

The chemical, mechanical, and automotive manufacturing sectors are most noteworthy. For chemicals producers the imposition of tariffs by both the UK and the EU would in all likelihood raise their cost of production and reduce demand for their final products. Moody’s estimates11 that 75% of chemical companies’ raw materials and inputs originate from the EU, and 60% of their final output is exported there. The impacts from tariffs could be further exacerbated by any backlogs at points of entry, which could disrupt their existing supply chains.

Finally, chemicals companies, domestic and foreign, are also facing several idiosyncratic factors. The foremost out of these is the UK-Reach data agreement, currently superseded by EU regulations, which in the event of a no-deal Brexit would require them to spend around £70,000 per substance to register chemical data with the UK. This agreement has left firms in somewhat of a no-win situation. If they spend to register their substances now, they run the risk of it being irrelevant should the UK and EU strike a deal in which existing data sharing arrangements are maintained. However, should they delay registration, they run the risk of suddenly not being able to sell their substances in the UK for a period of time.

The automotive and aerospace industries face their own set of challenges. Similar to chemical producers, these manufacturers have deeply-integrated supply chains across the EU. According to the European Automobile Manufacturers Association 80% of UK-imported automotive components originated from the EU last year. UK automakers are also disproportionally reliant on foreign demand for their cars, with 81.5% of cars produced being shipped outside the UK (of which a little over 50% goes to EU countries).

It is perhaps unsurprising then, that the auto industry has seen the most turmoil from the Brexit vote. Last year, auto production in the UK fell by 9.1% and new investment plunged by 46%, according to the Society of Motor Manufacturers. This fits with anecdotal news from the global car manufacturers. Honda decided to shutter plans for a new plant in the UK amidst the uncertainty, and Nissan has cancelled plans to produce its X-Trail SUV there. Toyota and BMW have also warned that Brexit could have a negative impact on their investment within the country. For BMW, this may well bode a future shift in production of its Mini brand outside the UK.

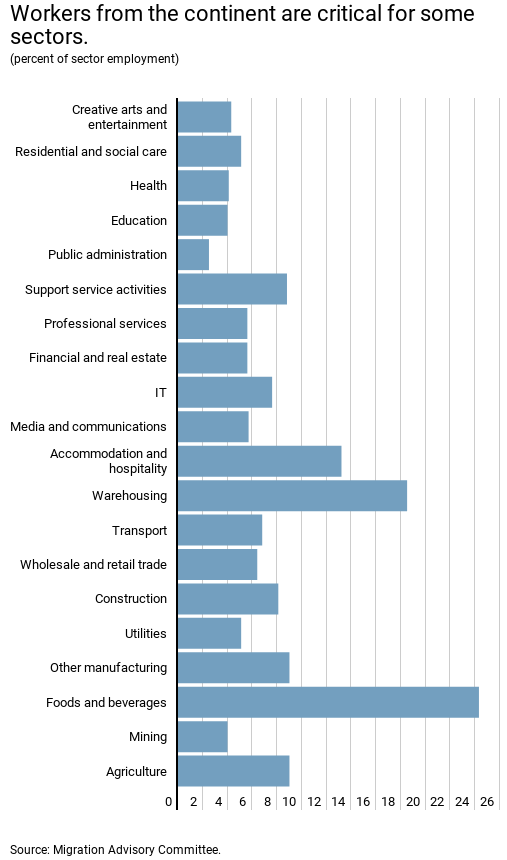

Outside of direct trade exposure, a number of industries also draw a significant amount of labor from the EU (Figure 8). The ability of firms to continue doing so will be hampered post-Brexit, as one of the UK’s primary goals is to inhibit the free movement of EU citizens into Britain. On the margin, the reduction in skilled labor will make the industries such as IT, professional services, and education less competitive and productive. And on the flip side of the coin, a reduction in unskilled labor will increase labor costs for food and beverage, agriculture, and warehousing companies.

Figure 8: European Economic Association Workers in the UK

Source: IMF, The Uneven Path Ahead: The Effect of Brexit on Different Sectors in the UK Economy

Restrictions on the flow of people and goods also has the potential to impact the travel industry. A loss of air travel rights to the EU would threaten almost 80% of air traffic through the UK. Additionally, several airports within the EU, such as Nice Airport in France, route a significant amount of their flights through the UK. Outside of this, newly imposed impediments to consumer travel12 have the potential to squeeze British and EU airliners’ profits. A weaker pound could also make travel outside of the UK less appealing, though it could also be a positive for travel into the UK.

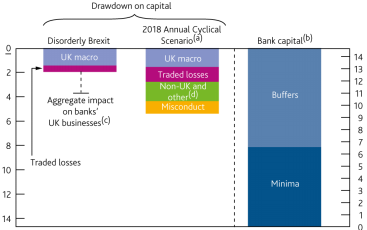

Finally, financial services firms within the UK would also be negatively impacted by a chaotic Brexit. A no-deal outcome holds the dual possibility of revoking passporting rights with the EU, while also leading to macroeconomic instability in the UK. The former would threaten UK banks’ ability to retain and service clients in the EU, while the latter would eventually work to undermine their profitability and asset quality. Nevertheless, the BOE determined that UK banks are well capitalized and liquid enough to continue operating in even the worst-case Brexit scenario. Figure 9 displays the projected impact of a disorderly Brexit on UK banks’ capital ratios, along with BOE’s even more severe stress test scenario.

Figure 9: European Economic Association Workers in the UK

Source: Bank of England, Stress Test Results

Nearly all the large banks have already undertaken significant amounts of contingency planning with a no-deal Brexit in mind. This includes transferring EU-based activities from London to subsidiaries outside of the UK to ensure that they can continue servicing clients even if they lose their passporting rights. Bank of America, for instance, moved the entirety of its UK operations to Dublin, while Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan have established new subsidiaries in Frankfurt.

The European Commission and UK government have also taken steps to reduce risk in the event of a no-deal. This includes ensuring the continuity of authorizations for financial services firms operating in both regions, as well as allowing EU firms to continue their usage of UK-based clearinghouses to process derivative transactions. The latter is especially vital given the size and importance of the derivatives market, which is in the trillions of dollars.

Conclusion

Given the fluidity of the situation, nothing with Brexit can be taken for granted. Nevertheless, after months of stagnation, the proceedings seem to have taken a turn in the right direction. Theresa May’s proposal to extend the deadline past March 29th was a tacit admission that no-deal is not a viable outcome. Additionally, declining public support for Brexit has led to a softening in rhetoric and political stance from the UK’s pro-Brexit conservatives. Perhaps most importantly, there is recognition that a deal remains in the best interest of all parties involved.

A negotiated deal would almost certainly leave the UK economy worse off than if it had decided to stay within the EU. Even so, the outline of a framework and a transition period would provide some clarity for UK businesses and consumers. This could in turn boost investment and consumption, which would help the UK recover some of its lost output. For investors, it would ease a significant tail risk, resulting in an easing of financial conditions and an improvement in credit quality over the near-term. Overall, it seems like the best possible outcome at this point.

On the other hand, the possibility of the UK crashing out of the EU without a deal still remains. As the BOE’s analysis showed, the downside risk is significant. A no-deal scenario has the potential to be disastrous for the UK and would almost certainly have global repercussions. The risk of contagion would be high, as equities markets would sell off, financial market volatility would rise, and credit conditions would tighten. Furthermore, any companies with direct exposure to the UK could face pressure on both their top and bottom lines simultaneously. This in turn could lead to negative rating actions and potential insolvencies. In light of this, it is imperative that investors have an understanding of their exposures and take the steps necessary to mitigate risk they cannot tolerate.

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

1This also comes after three of her party members defected in order to join the newly formed Independent Group, which includes 8 former Labour politicians. All three publicly criticized May as being beholden to pro-Brexit forces within her party.

2The Good Friday Agreement was a treaty signed in 1998 between the UK and Ireland which formally established Northern Ireland as part of the UK. It also established trading relationships between NI and IR and holds that NI would be allowed to rejoin Ireland should the majority of its citizens wish to do so. The agreement ended the period of sectarian violence known as “The Troubles.”

3The DUP was the only political party to oppose the Good Friday Agreement. They’re also a member of Theresa May’s governing coalition in Parliament.

4The only exception to this is a study done by the Economists for Free Trade (EFT), which makes wildly unrealistic assumptions about the UK’s post-Brexit trade partnerships.

5This would require the implementation of numerous tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade.

6It should be noted that this is only after the customs checks are instituted in 2021.

7The study finds that Brexit has led to a 12% shift in new investment by UK firms from the UK to the EU, as well as an 11% decline in new investment from the EU to the UK.

8Cited from a Capital Economics report entitled “Brexit scenarios- a recap.”

9An exception to this is the UK Government’s own estimation, which is line with the Bank of England’s.

10This assumes that WTO trade rules are instituted.

11Moody’s Report, “Probability of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit has risen, and would be negative for an array of issuers”

12These include border controls, revoking of EU travel insurance for UK citizens, and institution of mobile phone roaming charges.

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.