The Banks Are Alright

The COVID-19 pandemic produced the first major test for the U.S. banking system since the 2008 global financial crisis. At the start of the pandemic, questions were posed about how bank balance sheets would hold up amidst a period of social isolation, lockdowns, elevated job losses and a severe contraction in output. Would the banks’ credit quality deteriorate significantly, or had post-crisis regulation bolstered their ability to withstand a crisis?

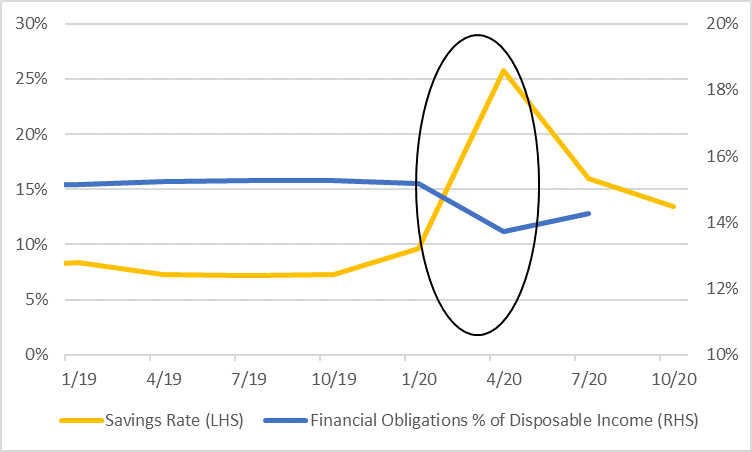

As 2020 results roll in, it is apparent that bank credit quality has held up well, best demonstrated by the quality of their loan books. At the genesis of the crisis, it was expected that banks would take significantly higher losses on their loan portfolios as borrowers experienced financial stress and defaulted. However, primarily due to unprecedented levels of government stimulus, this has not manifested. Household balance sheets have benefited from a combination of direct payments and expanded unemployment insurance, resulting in a decline in household debt expense and a rise in savings (Figure 1).

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Database

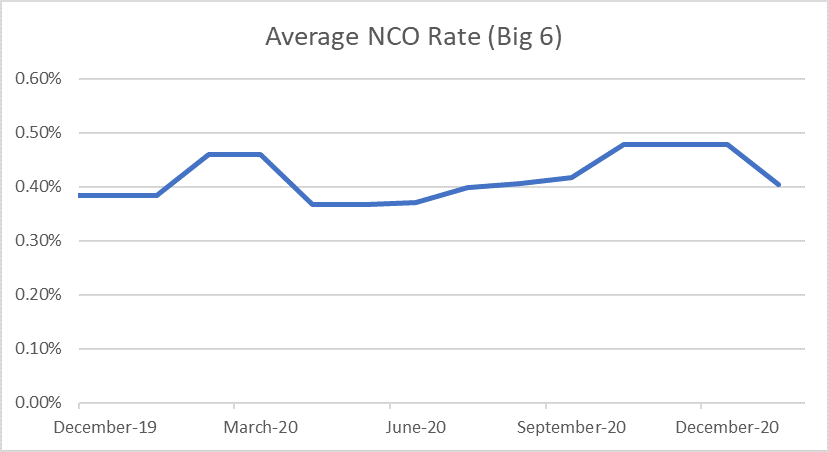

On the commercial side, companies have also benefited from government assistance, directly via PPP loans and secondarily via government support measures to support consumer spending. The upshot is that banks’ asset quality has experienced only minimal deterioration so far. In fact, average credit losses for the six largest banks1, as measured by Net Charge-Offs (NCOs), were only 2 basis points higher in Q4’20 compared to Q4’19 (Figure 2).

Source: Bloomberg

It is expected that the charge-offs will eventually rise as higher delinquencies roll through the system. In addition, banks offered extended forbearance programs to borrowers at the beginning of the crisis. This masked the true amount of bad loans to some extent, evidenced by the initial decline in NCOs in Q1. However, as S&P notes, the median rate of loans in deferral across U.S. banks declined from 8% in Q2 to just 1.1% at the end of Q4. By all indications, the vast majority of borrowers who have exited forbearance are current on their loans, and the remaining loans in deferral are largely mortgages, which tend to have lower loss rates than credit card and auto loans. Add on top of this the prospect of further fiscal support for consumers and businesses, and it is all but certain that actual losses will be significantly less than initially predicted2.

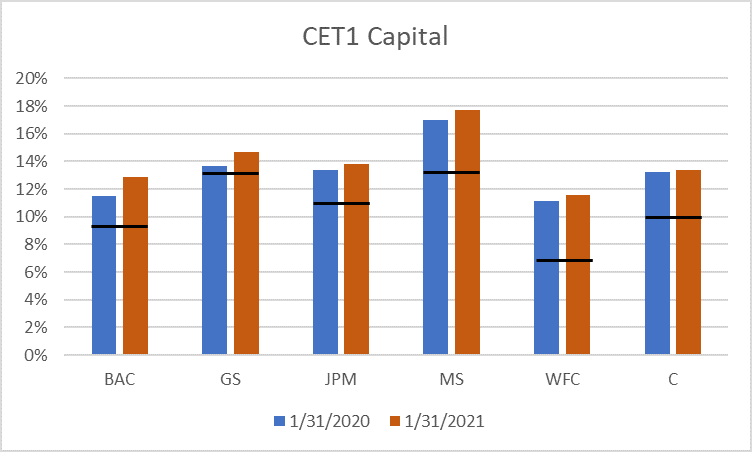

The other half of the equation is the loss-absorbing capacity of the major banks. As Figure 3 illustrates, banks were largely able to maintain or build upon capital levels in 2020. There are several reasons for this.

Source: Bloomberg

The first is that the Federal Reserve imposed a moratorium on share buybacks. This forced the banks to hold a greater portion of their earnings (everything outside of approved dividends) on balance sheet rather than paying them out to shareholders.

The second is that banks’ risk-weighted asset levels declined due to lackluster loan growth. The lack of demand for loans meant that banks held incremental deposits in cash or high-quality securities such as Treasuries instead of lending them out. This weakened bank profitability but resulted in stronger capital levels.

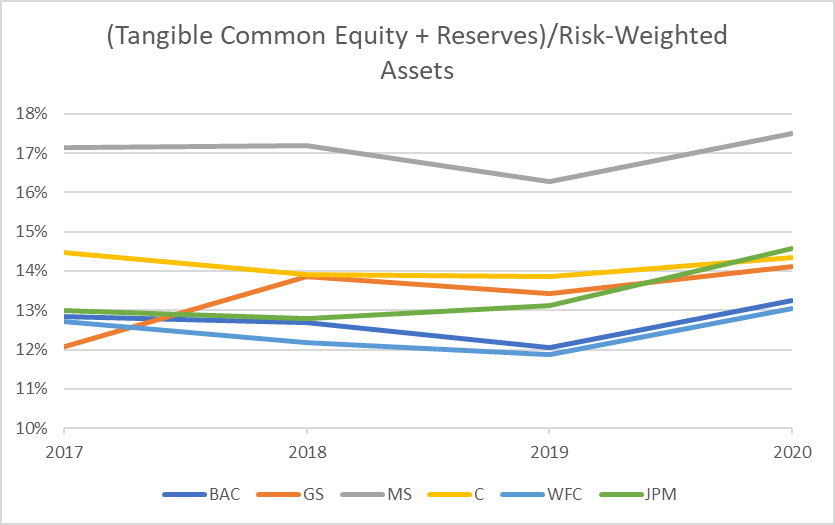

Finally, U.S. banks were aggressive in provisioning against potential loan losses at the onset of the pandemic. Over the course of 2020 the Big 6 banks set aside a cumulative $127B in reserves as an additional buffer against future loan losses3. Adding this on top of capital gives insight into just how much additional loss-absorbing capacity the banks have built up (Figure 4).

Source: Bloomberg

Outlook for 2021

The expectation is that 2021 will see a moderation or reversion of the trends that dominated 2020 as COVID-19 cases continue to decline, vaccinations rise and economic activity rebounds. Amongst other things, this could result in the following:

- Higher Profitability: Profitability was a weak point in 2020 due to tepid loan demand, low interest rates and high provisioning for loan losses. The expectation is that banks will release reserves as worst case COVID scenarios become less and less likely, and that loan demand will improve as economic growth picks up. The steepening yield curve, assuming it lasts, could also be positive for bank profitability.

- Weakening Asset Quality: It is expected that asset quality metrics will deteriorate somewhat in 2021, particularly in areas such as commercial real estate, which is challenged by secular as well as cyclical trends. However, the downside risk to asset quality has diminished as the pandemic has improved and the prospect of additional fiscal stimulus has risen. Additionally, there’s some talk, most notably from JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon, that peak loan losses might not be reached until 2022.

- Marginal Reduction in Capital: The Fed allowed the banks to restart share buyback programs in the first quarter at a limited level. It is expected that the Fed will eventually remove all restrictions at some point this year, allowing the banks to pay out excess capital. However, regulatory requirements and stress testing limit how much capital banks can draw down.

- Strong Liquidity: Bank’s liquidity positions improved greatly in 2020 due to an influx of deposits. While this should reverse somewhat, as spending picks back up and loan growth rebounds, the banks are likely to retain higher levels of cash and highly liquid securities than pre-pandemic.

There are still challenges to this outlook, the greatest being progress on the vaccine distribution and case suppression front. A surge in COVID cases, perhaps driven by a new COVID variant, could send the economy back into recession. This would have a knock-on effect for the banks, pressuring profitability and resulting in renewed questions about asset quality. Fundamental changes to people’s behavior could lead to challenges for individual industries such as retail and hospitality, putting pressure on loan books with exposure to those industries. The recent rise in interest rates could abate, and technological changes to the banking industry could leave some players lagging. Nevertheless, the banks enter this period in good shape to cope with these potential threats.

1As measured by assets: JP Morgan, Bank of America, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley

2As evidence of this, S&P continually reduced its baseline projections for bank credit losses throughout the year, starting at 6.3% of loans in April and coming down to just 2.2% by December.

3Figure according to Bloomberg data; FY 2020 cumulative loan loss provisions

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.