The Ghost, The Wall, and The Known Unknowns

DOWNLOAD FULL REPORT

Introduction

By Lance Pan, CFA

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

As the new year approaches and I prepare this introduction to our annual market outlook on cash investments, I can’t think of a better way to describe the past year than this quote by Charles Dickens.

Last year, our credit team identified three themes in our 2023 outlook: a) interest rates nearing an inflection point, b) continued higher commodity prices, and c) banks heading off consumer credit risks. We were spot on with the Federal Reserve System (“the Fed”) at an inflection point, as it managed to hike the fed funds rate by 75 basis points (bps) more than the market had expected and held it there for five months and counting. At the December Fed meeting, the central bank officially pivoted towards easing in 2024. Despite a market consensus outlook of a shallow or moderate recession in 2023, gross domestic product (GDP) rebounded to 4.9% in the 3rd quarter. Headline consumer price index (CPI) improved from 7.1% at the end of 2022 to 3.1% in November, and the unemployment rate remained low at 3.7%. In this regard, 2023 was the best of times indeed.

As for our prediction on commodities, they were a mixed bag this year, with moderately lower crude and agricultural prices but a 58% spike in gold futures as of December 20th.

On the credit side, the risk from rising consumer debt burdens leading to bank failures did not materialize, but high uninsured deposits and massive unrealized losses of Treasury securities led to three of the four largest bank failures in history (i.e., Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank), all within two months of each other. By the end of the year, deposit outflows and interest margin compression have moderated or stabilized without a significant rise in credit losses. Banks are in a stronger position for 2024 than a year ago as the Fed is poised to lower rates.

Looking to 2024, the strange melancholy in the market last year has now been replaced by a strange euphoria, with a powerful rally in risk assets riding on the impending rate cuts. Yet the Fed itself acknowledges that the road to 2% inflation is likely to be a long one, with a good chance of a long pause before cutting; and dare we say even a hike or two? A knock-on effect of the long Fed pause likely will be felt on the high pile of corporate debt issued at low coupon rates in the lean COVID-19 years that must be refinanced at much higher costs. In climbing this wall of maturing bonds, some credits may fare better than others.

Lastly, the world is not at peace. A second regional war, the Israel-Hamas war, in addition to the war in Ukraine, threatens political balances and global energy prices. The Russian oil embargo and the spy balloons accelerated the drifting apart of the U.S. and China in the glacial shift of deglobalization, with geopolitical, economic, and financial implications. Adding to the juxtaposition of risks is a deja vu presidential election in the U.S. that is more divided than in two previous election cycles.

With this context in mind, our analysts will dig into these themes for 2024:

- Ghost of the great inflation haunting the Fed in rate cuts

- Corporate credit staring down the great (maturity) wall

- Known unknowns in deglobalization may threaten growth and inflation

Ghost of the Great Inflation Haunts the Fed in Rate Cuts

By Pate Campbell, CFA

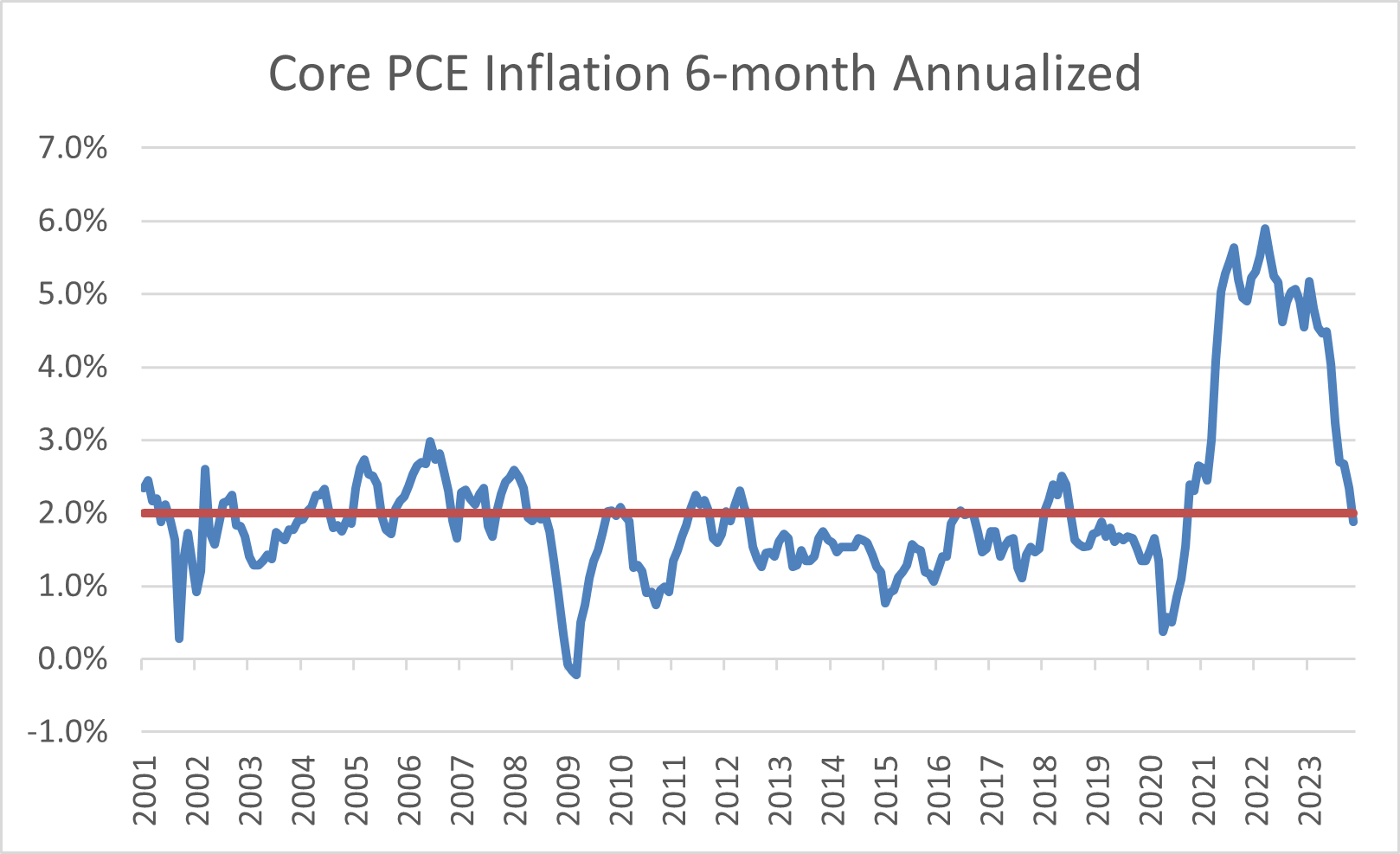

The December Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting marked a distinct dovish pivot in which, for the first time in this cycle, Fed Chair Jerome Powell acknowledged discussing the timing of potential rate cuts. This, combined with a summary of economic projections which showed lower expectations for both the Fed Funds rate and inflation through 2024, led to mass repricing in fixed income markets. However, the Fed has continually emphasized that monetary policy decisions have been and will remain dependent on incoming economic data and maintains that additional hikes are not completely off the table. A still tight labor market, signaled by a 3.7%1unemployment rate and 4.9%2 annualized 3rd quarter GDP growth, could mean slow going for the last mile to 2% inflation. However, inflation’s steady march downward through 2023, illustrated by a six-month annualized core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) decline, from 5.9% in March to just 2.5% in October, nearly greenlighted the Fed to begin rate cuts3. Following the Fed’s December meeting, November core personal consumption expenditure on a six-month annualized basis dropped a further 60bps to 1.9% confirming the trend4.

Markets have embraced a Goldilocks scenario of gradual cuts without a significant drop in economic activity. As a result, investors are focusing on when, not if, the Fed will cut rates in 2024. Markets currently anticipate the first cut at the Fed’s March 2024 meeting, and over six cuts total in 2024.5 However, risks to the economic outlook have become more “balanced” as Powell says, ensuring that monetary policy’s path this year is not set in stone.

Figure 1: Bloomberg

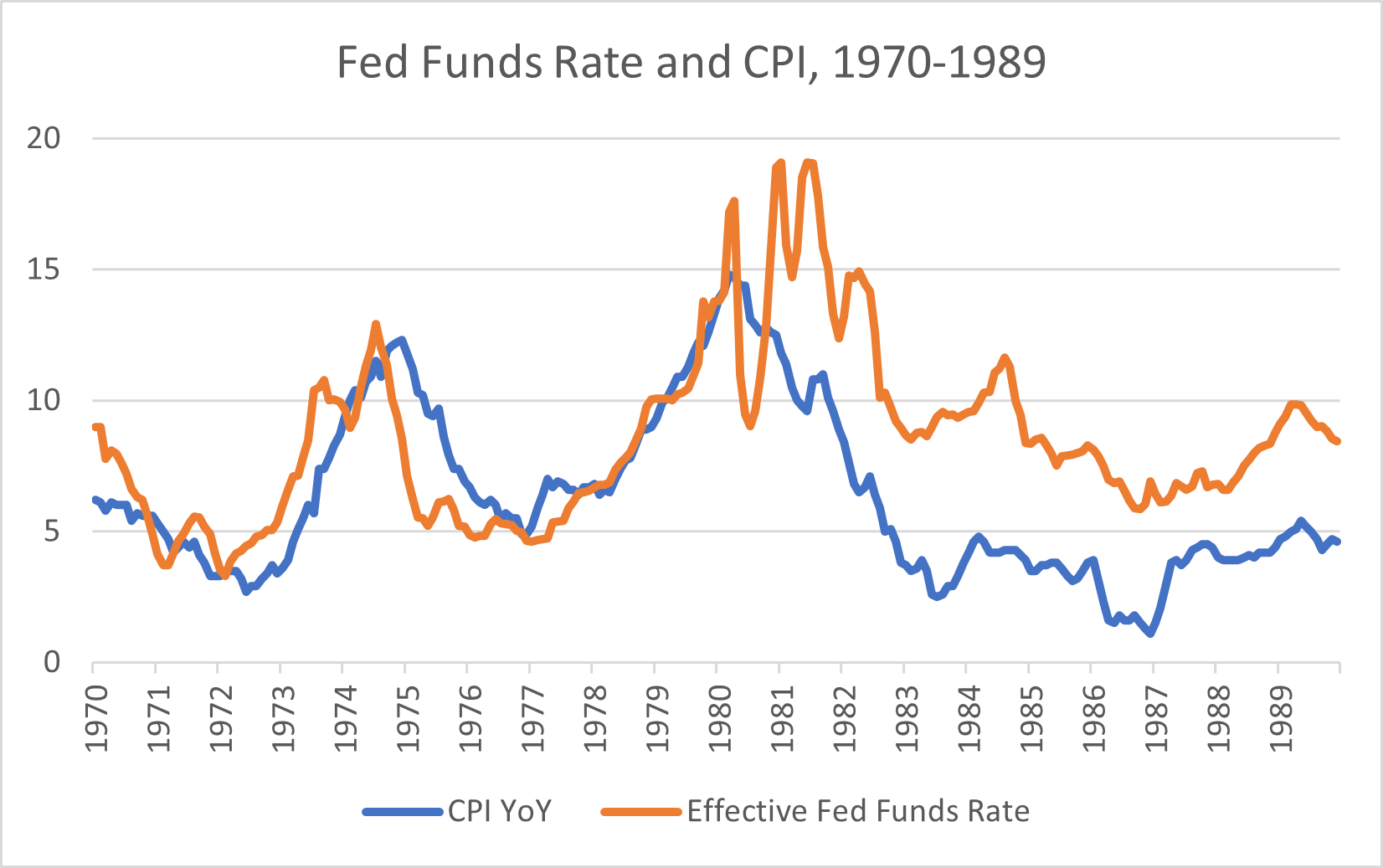

During the Great Inflation of the 1970’s and 1980’s, the Fed repeatedly cut rates as inflation ebbed, only for it to resurge again. Multiple premature cutting cycles eventually led to double digit inflation, which was only squashed by a painful 19% hiking campaign led by then Fed Chair Volcker. The Great Inflation’s memory is still fresh in the Fed’s mind.

Figure 2: Bloomberg

This history has made officials hesitant to take additional hikes completely off the table. This much was clear in Chair Powell’s December 1st speech at Spelman College.

“The FOMC is strongly committed to bringing inflation down to 2 percent over time, and to keeping policy restrictive until we are confident that inflation is on a path to that objective. It would be premature to conclude with confidence that we have achieved a sufficiently restrictive stance, or to speculate on when policy might ease. We are prepared to tighten policy further if it becomes appropriate to do so6.”

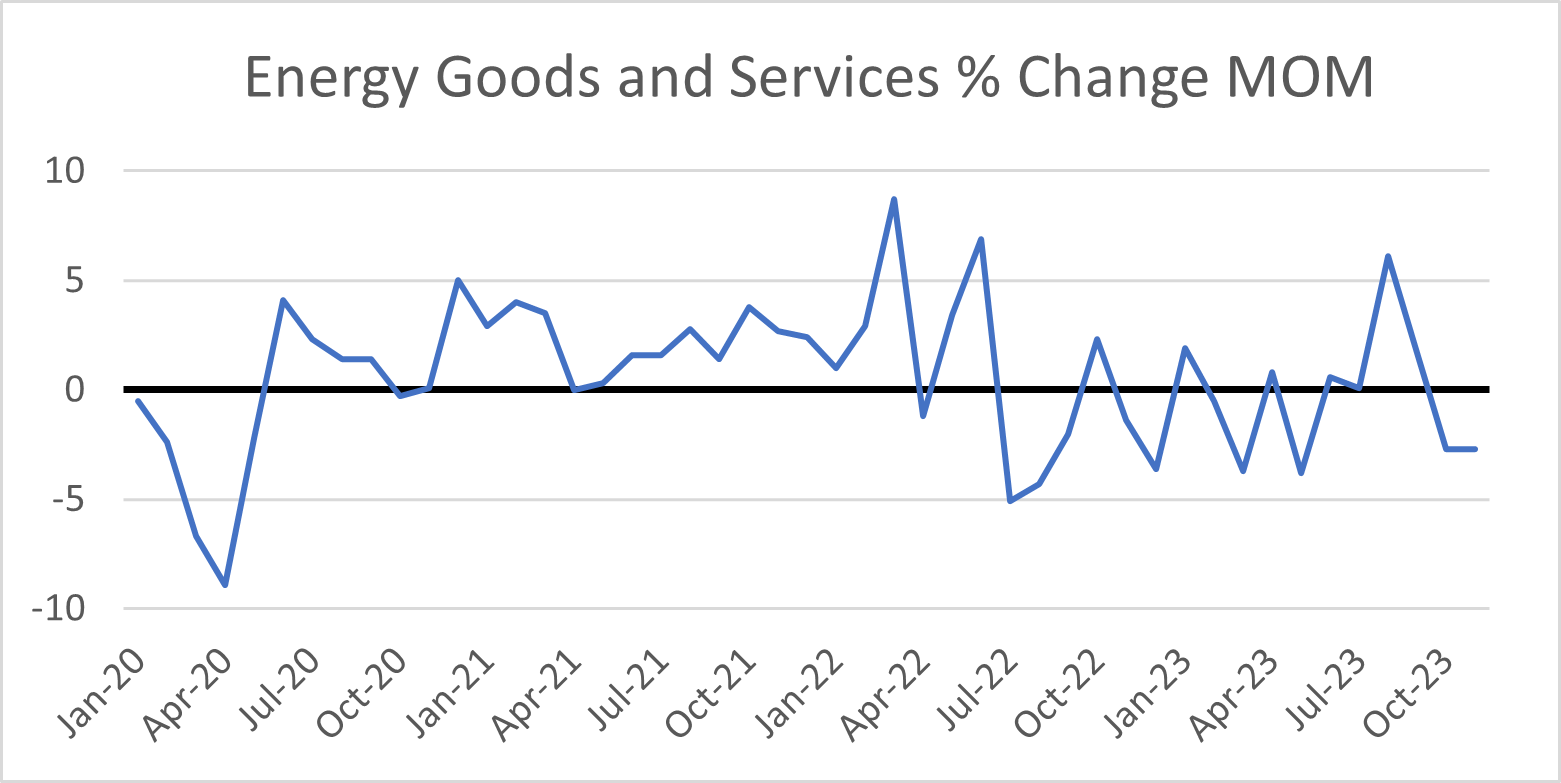

Volatile energy prices could also present a serious threat to inflation’s path towards 2%. A 6.0% decline in energy prices between November 2022 and 2023 helped to drag down November headline inflation7. While the Fed tends to look through energy price spikes, its mandate is to promote stable prices, not stable core prices. Additionally, energy’s role as a universal input of production means price spikes may have significant knock-on effects for the prices of other goods. The on-going war in the Middle East and OPEC+’s recent production cuts could threaten energy’s deflationary trend. Even without these shocks, high energy prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are falling out of the data set, meaning, all else equal, energy will contribute less to lowering inflation in the future.

Figure 3: Fred

Likewise, the unraveling of pandemic era supply chain snarls and consumers’ shift to spending on services have resulted in outright deflation in goods prices, which has helped to pull headline and core measures of PCE towards 2%. However, base effects related to previously high goods prices and new threats to supply chains, such as low water levels in the Mississippi River8 and Panama Canal9, could slow or stop goods’ deflation. A disruption of these trends could lead the Fed to have a higher terminal rate in 2024 than the 3.85%10anticipated by markets.

Conversely, what could push the Fed to start cutting sooner and more than anticipated in 2024? Inflation coming down, of course. More specifically, officials are looking to be convinced that inflation is coming down in a sustained and consistent manner before they begin seriously considering cuts. In a November 28th speech, Fed Governor Christopher Waller cited housing inflation, which is lagged in PCE calculations, as being a moderating factor for inflation readings over the short-term11. He also discussed falling employment costs as helping to bring down still hot services inflation. Average hourly earnings growth has fallen considerably to 4.0% since peaking in 2022 but remains above pre pandemic growth rates of roughly 3.0%12. However, the Employment Cost Index (ECI), a much broader measure of employment costs, has not fallen quite as drastically13.

To be truly confident that inflation is on a sustainable path down, the Fed needs to see loosening labor market conditions and slower economic growth. The Fed’s most recent Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) suggests Fed officials believe the long-term equilibrium for unemployment and potential GDP growth rates are 4.1% and 1.8%, respectively14. This suggests that unemployment consistently above and real GDP growth consistently below these levels would make officials significantly more comfortable about cutting. The more evident the economic headwinds, the more comfortable they likely would feel pursuing more cuts.

The path of rates in 2024 will be dependent on trends and the broader economic picture rather than specific markers. Continued tight labor markets may lead to less cuts, while below trend growth should lead to more. That said, the Fed likely will shoot to begin cuts before inflation reaches 2%, as real rates rise with lower inflation and to account for monetary policy’s long and variable lags. Serious exogenous shocks such as this spring’s banking crisis or a broader war in the Middle East always remain potential outliers which would likely force the Fed to cut rates more abruptly, and to a lower level than otherwise anticipated. However, if all goes well this year, the Fed should cut rates throughout 2024 in a controlled manner.

Corporate Credit Stares Down the Great (Maturity) Wall

By Matt Paniati, CFA

2024 may prove to be a pivotal year for corporate credit. One story of the cycle-to-date has been credit’s surprising resilience. While credit indices have been hurt by rising rates, credit spreads have tightened, and credit quality has held up better than expected. Ratings upgrades have outnumbered downgrades, and the number of companies promoted to investment-grade has outpaced the number relegated to speculative grade by a factor of 3x15.

Nevertheless, the first signs of potential cracks may be beginning to show. Corporate profit levels have retreated modestly from their recent peak, down ~1% from the third quarter of 202216. More significantly, default rates have now risen off their historic lows following the initiation of pandemic recovery programs. The speculative default rate recently hit 4.5% according to Moody’s, more than twice the Q1 2022 level and above the long run average of 4.1%.

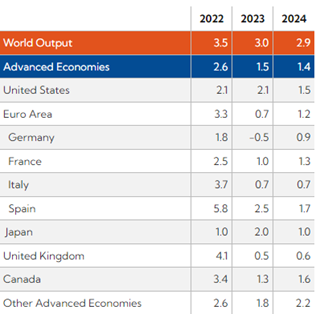

Looking forward, the outlook for corporate credit is tightly interwound with the health of the global economy, such that a primary driver of defaults is whether a soft landing is achieved. And while the economic outlook has arguably improved in recent months, this outcome is far from certain. Under its base case scenario, the IMF is projecting a further weakening of growth in 2024, with particular soft spots in Europe and the UK.

Figure 4: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2023 edition

Amplifying the stakes is the wall of debt coming due over the next few years. As noted in our recent piece Tightening Financial Conditions May Cause Us to Lose Circulation, firms issued a large amount of debt at the height of the pandemic in 2020-2021, taking advantage of record low interest rates to shore up their cash positions and ensure manageable interest expense costs for the medium term. The upshot of this phenomena is that businesses have had limited debt rollover thus far, insulating them from the impact of the increase in interest rates.

This will begin to change as pandemic debt becomes due. Speculative grade issuers face a difficult outlook, with Barclays estimating that the sector is confronting a record maturity wall over the next two years. According to their analysis, $130B in high yield bonds are due in 2024-2025, equating to ~7.5% of Bloomberg’s High Yield Index (a proxy for the high yield debt market). They estimate that the cost of refinancing this debt will add > 200 basis points in interest expense for issuers.

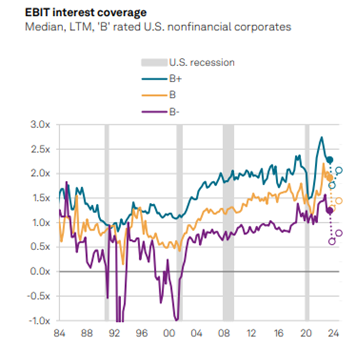

This, in turn, has negative implications for interest coverage ratios. S&P projects that high yield corporates’ interest coverage ratios will fall from their current levels, with B rated issuers in particular declining below the 1x threshold. This is likely to manifest in higher downgrades and defaults relative to levels seen over the past few years.

Figure 5: S&P Global Credit Outlook 2024

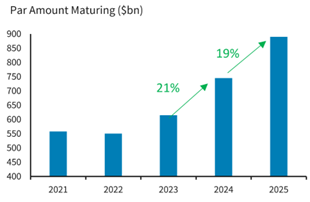

The investment grade universe is also set to see a commencement of refinancing activity. Barclays estimates that the universe faces a $745B wave of maturing debt in 2024, a 21% increase from the year prior. The trend continues into 2025, when maturing debt is expected to rise a further 19%.

Figure 6: Barclays FICC Research

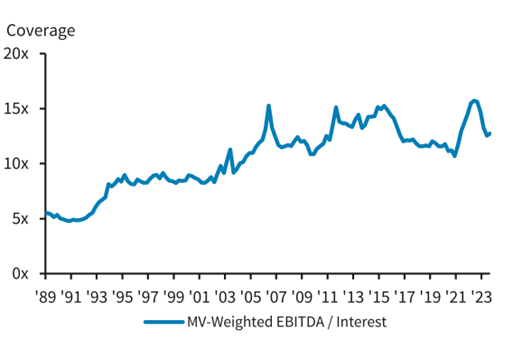

However, credit fundamentals in the universe remain strong. Companies used the past few years of strong revenue growth to reduce leverage and unload inventories, bolstering their cash positions in the process. Additionally, despite the modest decline in corporate profits, operating margins remain near three-decade highs. This means that even though interest coverage ratios are likely to come down over the next few years, they will be doing so from a comfortable level (see Figure 4).

Figure 7: Barclays FICC Research

It seems then that the incoming maturity wall poses less of an acute problem for higher-quality credits than lower-quality ones. This is reflected in current ratings outlooks, with S&P holding Negative outlooks on 20% of speculative grade companies compared to just 9% of investment grade ones17. Nevertheless, we are on the lookout for a few general risks, namely:

- Heightened Financial Market Volatility: An uptick in volatility could make it more difficult for corporates to refinance their debt at reasonable levels. A worst-case scenario would be something like March 2020, in which heightened uncertainty over the pandemic led to a massive sell-off in risk assets and full-on freeze in funding markets. It’s impossible to predict this sort of event ahead of time, but the risk is heightened due to the steep rise in interest rates over the past two years.

- Recession: This is not our base case forecast, but a recession would exacerbate pressure on firms by putting downwards pressure on consumer spending, and thereby revenue bases.

- Resurgence of Inflation: Inflation is currently in full-fledged retreat. However, there is risk of this reversing due to supply or demand side pressures. A rise in inflation would put upwards pressure on physical input and labor costs, which could pressure margins if firms are not able to offset them via higher prices (see previous section).

The primary risk to the credit outlook is that one of these issues exacerbates the pressure from rising interest expense on corporate profit margins and liquidity. Even so, investment-grade corporates’ strong performance and prudent balance sheet management since the onset of the pandemic leave them well-positioned to weather the coming storm (should it manifest). Credit ratings may not improve from here, but credit quality looks to be resilient.

Known Unknowns in Deglobalization Threaten Growth and Inflation

By Alexander Goldman

Pandemic disruptions revealed the risks of globalized supply chains. While these have largely been resolved, they kicked off a deglobalization wave that has continued amid ongoing geopolitical crises and an increasingly fractured world.

Despite the recent reestablishment of top-level contacts, tensions between the U.S. and China appear to be a great risk factor, manifesting itself through export restrictions, increased tariffs, and territorial jockeying. In January 2023, the U.S. initiated export restrictions on leading-edge semiconductors to China which could be used for military purposes. These restrictions were also an attempt for the U.S. to maintain their advantage in the global race to develop artificial intelligence, which could potentially increase workforce productivity but also poses cybersecurity risks which the U.S. seeks to mitigate.

Geopolitical tensions have also impacted key elements of the energy transition. In October, China limited exports of graphite, which makes up 40% of an EV battery, complicating the U.S.’s push for vehicular electrification. 18 A month later, the Biden administration disqualified Chinese EVs from the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax credits, which further slowed domestic EV adoptions.19 Additionally, China’s manufacturing dominance of goods key to energy transition, such as solar panels, subjects transition progress to rising tensions between the U.S. and China and potentially jeopardizes scaling of alternative fuels.20 Moreover, Saudi Arabia, a tentative ally of the United States, has become closer to China (and Russia) perhaps due to the U.S.’ aggressive rhetoric against fossil fuels. While China has also invested heavily in renewables, they are targeting net zero by 2060, 10 years later than the 2050 target laid out by the Paris Climate Accord, giving the fossil-fuel exporter a longer runway. Other major fossil fuel exporters may also adjust their stances based on different energy transition plans, which could alter global alliances.

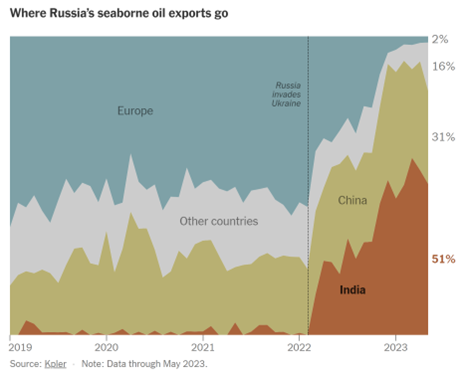

Friend-shoring has been another side effect of deglobalization, perhaps best evidenced by the change in energy trade following the invasion of Ukraine. Previously, Europe had received 30% and 40% of its oil and gas, respectively, from Russia, but sanctions imposed by the West shifted the continent’s reliance towards the U.S.21 Meanwhile, China and India picked up some of the slack from reduced European demand, taking advantage of price caps on Russian oil.

Figure 8: New York Times

The result of these trade tensions and friend-shoring has created a fractured world somewhat reminiscent of the Cold War, increasing the risk of supply shocks should tensions reignite. Further supply export restrictions could create inflationary shocks that pose long-term inflationary challenges for the Federal Reserve. Greater trade barriers also may affect foreign investment and growth opportunities and could thereby reduce global growth.

To date, the impacts of existing tariffs in industries such as technology and automotive have been relatively muted and have not spilled over to other sectors, or the broader global economy. Presidents Biden and Xi Jinping met in November to work towards improving U.S.-China relations, perhaps a tacit acknowledgement of the downsides of current hostility. However, foreign investment trends are unlikely to improve without firm, long-lasting incentives currently not on the table, further dividing global economies. Additionally, should a more isolationist presidential candidate win the 2024 U.S. election, relations could be further strained. Such impacts, if any, would not be felt until at least 2025.

Ultimately, geopolitical risks in 2024 are widespread and encompass a broad spectrum of known unknowns. While such things are near impossible to predict with total accuracy, recent trends towards deglobalization and friend-shoring have shown limited signs of dissipating, casting a cloud over global growth and inflation. Despite lower inflationary risk compared to the last two years, the current economic environment remains fragile given higher interest rates, signs of employment headwinds, and expected slowing of global growth.

Conclusion: Portfolio Duration Extension with Laddered Maturities in 2024

Despite my allusion to Dickens in the opening, we hold guarded optimism for 2024 as lower rates often lift many boats. The Fed looks set to claim credit for a rare soft landing, guiding inflation towards its 2% target without destroying growth or killing jobs. Lower rates reduce funding costs and lessen stress on credit. Recent high-level talks between the U.S. and China are signs of both sides’ reluctance for wider confrontations. A strategy of extending portfolio duration with laddered maturities may offer protection against lower future rates and help retain liquidity and flexibility for reinvestments in case the Fed pauses longer than the market expects.

1U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Situation: https://www.bea.gov/news/2023/gross-domestic-product-third-estimate-corporate-profits-revised-estimate-and-gdp

2Bureau of Economic Analysis, Gross Domestic Product (Second Estimate) Corporate Profits (Preliminary Estimate) Third Quarter 2023: https://www.bea.gov/data/gdp/gross-domestic-product

3Bureau of Economic Analysis, Personal Income and Outlays, October 2023: https://www.bea.gov/news/2023/personal-income-and-outlays-october-2023

4Bureau of economic Analysis, Personal Income and Outlays, November 2023: https://www.bea.gov/news/2023/personal-income-and-outlays-november-2023

5Refinitiv Workspace

6Jerome Powell, Fireside Chat at Spelman College: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20231201a.htm

7Bureau of Economic Analysis, Personal Income and Outlays, October 2023: https://www.bea.gov/news/2023/personal-income-and-outlays-october-2023

8National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Mississippi River Hit Record-Low Levels in October: https://www.noaa.gov/news/mississippi-river-hit-record-low-levels-in-october#:~:text=The%20Mississippi%20River%20ran%20historically,second%20year%20in%20a%20row.

9The Wall Street Journal, Panama Canal to Halve Daily Sailings This Winter Due to Drought: https://www.wsj.com/business/logistics/panama-canal-to-halve-daily-sailings-this-winter-due-to-drought-3bd70c79

10Refinitiv Workspace

11Christopher Waller, Something Appears to Be Giving: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/waller20231128a.htm#:~:text=It%20seemed%20clear%20to%20me,would%20stop%20or%20even%20reverse.

12Refinitiv Workspace

13U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Cost Index: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/eci.nr0.htm

14Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Summary of Economic Projections: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20230920.pdf

15According to Bloomberg, Moody’s has issued 1851 upgrades over the past three years compared to 1611 downgrades and rising stars have outnumbered falling angels 131 to 42. Stats are limited to North American companies.

16On a quarterly basis. Source: https://www.bea.gov/news/2023/gross-domestic-product-second-estimate-corporate-profits-preliminary-estimate-third

17Taken from S&P’s Global Credit Outlook. Figure as of 12/4/23

18https://markets.jpmorgan.com/#research.article_page&action=open&doc=GPS-4563975-0

19https://www.wsj.com/business/autos/biden-to-limit-chinese-role-in-u-s-ev-market-0fea206b?page=1

20https://www.iea.org/reports/solar-pv-global-supply-chains/executive-summary

21https://markets.jpmorgan.com/#research.article_page&action=open&doc=GPS-4073189-0

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.