How to Assess the Coronavirus Outbreak’s Impact on Liquidity Portfolios

Abstract

While the flood of information on the new coronavirus can be overwhelming, treasury professionals should consider how the outbreak may affect their liquidity portfolios. The consensus market view is that the epidemic will have a moderate and temporary impact on the world economy. We think the 2003 SARS epidemic and the current outbreak may not be comparable, as China now represents a larger proportion of the world economy. We provide a simple process for readers to assess the outbreak’s impact on their portfolios. Reducing exposure to exposed credits may be one solution, and improving liquidity by focusing on strong, well-known credits also helps. A moderately longer portfolio may offer some yield protection. While panic is not the solution, some alertness to potential tail risks is warranted.

Introduction

The outbreak of a new coronavirus first discovered in the Chinese city of Wuhan has quickly became the biggest headline of the new year. Our thoughts and prayers are with the patients and their families, medical professionals and support personnel on the frontlines. While the volume of information on confirmed cases and deaths, travel restrictions and factory shutdowns can be overwhelming, managers of liquidity portfolios need to remain vigilant regarding the potential impact of the outbreak on their portfolios.

We are not experienced virologists nor rapid response specialists with answers to this global public health emergency. Rather, we offer a thought process to help our readers digest news with an eye towards the safety and liquidity of institutional cash portfolios.

We will start with a brief recap of the outbreak. Thanks to its outward comparability to the 2002-2003 SARS outbreak, we will highlight the economic impact from that episode. We will suggest a way to look at this outbreak’s impact on economic growth, interest rates and credit, as well as on the liquidity characteristics of an investment portfolio. We’ll end with advice to stay vigilant to fight off complacency and to improve portfolio readiness.

A Brief Recap of the Outbreak and the Market’s Reaction

The new coronavirus, which the World Health Organization (WHO) has named COVID 19 (for Coronavirus Disease 2019), first turned up at hospitals in Wuhan in early December 2019, but did not receive widespread attention until January 20th, when a prominent epidemiologist on China’s CCTV confirmed person-to-person transmissions. It is similar to the coronavirus responsible for the severe acute respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2002-2003 that killed 500 people and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2015. This fast-spreading virus resulted in more than 60,000 confirmed cases and 1,300 deaths by February 12th (according to Johns Hopkins University and WHO). As a result, China placed Wuhan and nearby cities totaling more than 50 million population under a medical quarantine.

Much about the virus is still unknown, but the rate of transmission and rising death toll caused WHO and the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to declare the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) and public health emergency (PHE), respectively on January 30th. Major airlines suspended flights to China and Hong Kong and the US and several other countries warned their citizens not to travel to China. The possibility of asymptomatic transmission and difficulty of diagnosis have added to public’s concerns about the containment of the outbreak.

Financial markets zigged and zagged on concerns of the outbreak’s potential impact on global growth. Several Wall Street firms offered their estimates on its impact to China’s GDP, disruptions to global supply chains and volatility in the stock, bond and commodities markets. As multinational firms including Starbucks, McDonald’s, Apple, Ford and Google announced temporary closures, investors’ attention turned to downward revisions to corporate earnings and the drag on the US GDP. Bond yields dropped across the yield curve. Some market commentators started to wonder aloud whether the outbreak could be the external force that would end the longest economic expansion in recent US in history.

Comparisons to SARS and Other Disasters

The new coronavirus is 97% identical to the 2002-2003 SARS virus from a genetic standpoint. These similarities led some market participants to review that outbreak’s aftermath as a point of refence.

SARS infected 8,096 people (5,327 in China) with 774 deaths and a fatality rate of 9.6%. Sequential GDP growth in China slowed from 10.5% in the last quarter 2002 to 3.4% in the first quarter 2003. Despite its crushing damage to the local economy, SARS was brought under control around May of 2003, allowing a full economic recovery by the end of the year. The economy staged a powerful 13.5% rebound in GDP growth in the second half of 2003 to end the year with 9.1% annual growth, compared to 8.0% in 2002. The estimated negative impact of SARS on world GDP was 0.0%-0.1%.

During SARS, the sectors that experienced the most severe downturn were the travel, retail, and transportation industries. Impact on other sectors, such as exports, industrial production, construction, and fixed asset investments was muted. The transitory effect was seen by ramped up factory activities to make up for lost production. Thus, despite a very bad outbreak, the macro impact on the global economy was relatively modest.

Earlier estimates of the new virus’s similar transmission rate of 2-3 people (i.e., rate at which 1 infected person could transmit infection to other people) and lower fatality rates of 2.0-2.5% (i.e., rate of deaths caused by infection) led to some optimism that its economic impact would be less severe than SARS. However, judging from climbing case numbers and the extent of shutdowns, this optimism may turn out to be premature.

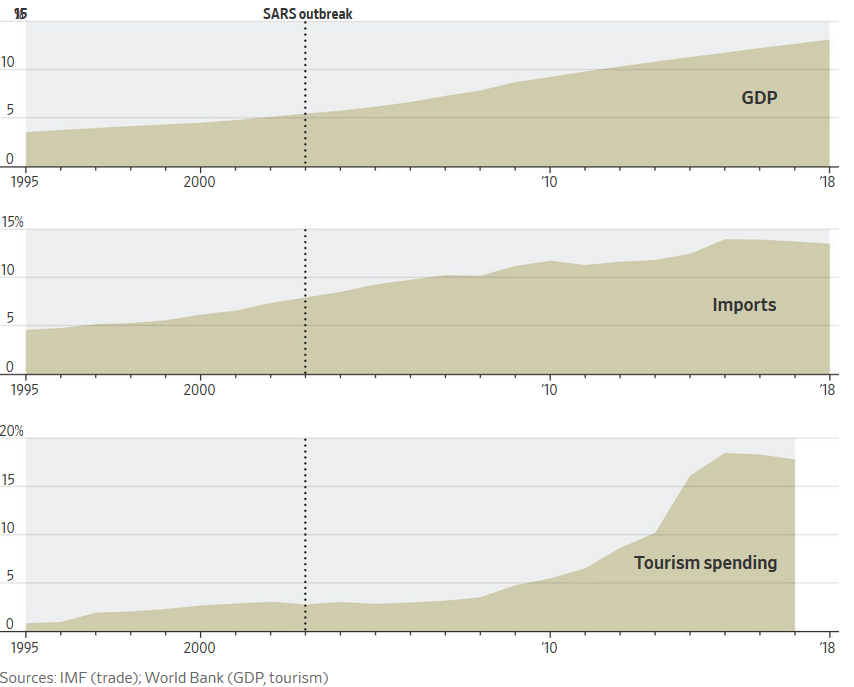

Compared to 2003, China’s share of the global economy has grown significantly, from 5% to 18% as of 2019. Increased disposable income boosted outbound tourism spending from 2% of global spending to nearly 20% in 2015. More importantly, China is today a far more important link in the global supply chain with its share in global merchandise exports twice the size as in 2003. Seven of the 10 busiest global container ports are in China, according to United Nations figures. While most factories remained open in 2003, the lockdowns, extended holidays, travel restrictions and office closures in the current crisis will result in lower or delayed production for months to come.

The Chinese government’s rapid response to stop the spread of the virus supports the comforting idea that the outbreak may come under control more quickly than SARS. But skeptics who have criticized the central and local governments’ initial efforts to cover up the epidemic have pointed to the spikes in new confirmed cases as proof that large-scale quarantines have not only failed to contain the virus, but also may be causing panic and cross-contamination as people hide their symptoms while seeking to be reunited with their loved ones.

In short, the economic impact from this outbreak may be worse than SARS.

Figure 1: China’s Share of the Global Economy

Source: IMF, World Bank

Comparisons to several other past disasters may also be useful. The floods in Thailand in 2011 and the earthquake and nuclear meltdown in the same year in Fukushima, Japan, resulted in long-lasting disruptions to supply chains, leading to assembly shutdowns in Korea and the United States and Europe even after immediate problems were fixed. A research report in 2015 showed that up to 60% of the total economic impact of Japan’s 2011 earthquake was felt in other countries, with 25% of the impact experienced by the US1.

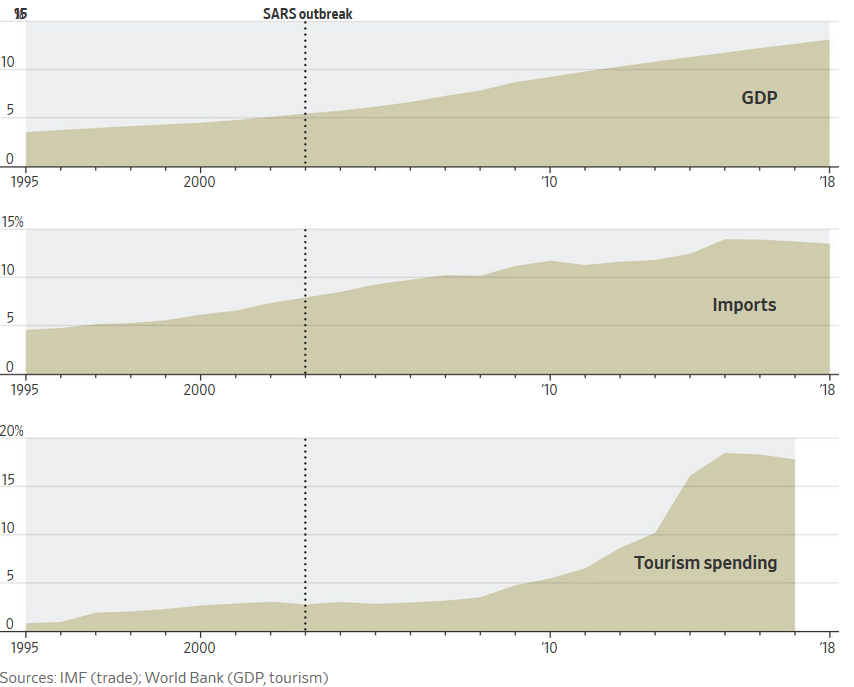

A Roadmap to Assessing Impact from Disasters like COVID-19

News of tremendous human suffering accessible via smartphones makes the outbreak a gripping human-interest story. The flood of information and analysis can be overwhelming to process and can sometimes lead to decision paralysis. From the vantage point of managing institutional liquidity portfolios, we hope to help our readers with this simple diagram. The objective is not to keep up with the rapidly changing information flow, but rather to sort and catalog how the flow of data impacts portfolio decision making.

Figure 2: How A Disaster May Affect A Liquidity Portfolio

Source: Capital Advisors Group

Simply put, all impact assessments go back to the safety, liquidity and yield objectives of short-term portfolios. When analyzing the relevance of market events to portfolio safety and liquidity, one should ascertain both the immediate impact from the events and their longer-term implications. Locality of events and how their concentric circles of influence reach US-centric liquid assets are also relevant to the analytical process.

In terms of the factors to consider, most of the information falls in one of the four categories: macroeconomic, interest rates, earnings impact, and financial market volatility. We will briefly discuss each of the categories.

Macroeconomic Impact

Macroeconomic impact analysis is fundamental to understanding significant news events. Epidemics, when contained quickly, tend to have a mild short-term effect on the local economy as activities bounce back within a relatively short window. If not contained, outbreaks may spread to larger areas with more ramifications on human behavior and business activity, which can result in government actions to help lessen the blow to the economy. To put things in perspective, combined import and export exposure in goods and services in the US from China was $737 billion as of 2018, or about 3.4% of our total GDP. This seems to suggest that if the outbreak can indeed be contained within China, potential economic impact on the US will be manageable.

Major Wall Street firms including JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Goldman Sachs as well as credit rating agencies were quick to fire up their forecasting models. Most predicted that the negative impact to GDP will most likely be localized in China and Hong Kong and only for one to two quarters. Most believed that the impact on the US economy will be muted. For example, Goldman Sachs estimated that the outbreak will reduce US economic growth by 0.4% in the first quarter, but that a rebound of 0.3%-0.4% in the second quarter will mostly offset the first-quarter decline. Economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal lowered their first quarter GDP estimates for China by only one percent to 4.9%2. Most reports also included the necessary disclaimer that their assessments took a blueprint from the 2003 SARS pandemic and that the duration and severity of the current outbreak may significantly alter their projections.

Complicating the matter will be the execution of the just-signed “phase one” trade deal that requires China to buy $200 billion in additional goods and services from the US, most of which will be from the agricultural and energy sectors. With reduced demand and transportation delays, it is difficult to fathom that the lofty goal is achievable. How this “breach of contract” will affect enforcement of the trade deal or the “phase two” negotiations remain open questions.

Interest Rates and Central Bank Responses

More than other financial products, liquid portfolios respond directly to the monetary policy of the Federal Reserve, and to a lesser degree, to decisions by central banks in other developed markets. A negative market event often leads to flight-to-safety trades, resulting in lower bond yields. When negative sentiment lingers and concerns about recession grow, central banks may be forced to cut interest rates, leading to lower portfolio yield and income potential.

Figure 3: 10-year and 2-year Treasury Yield History

Source: Bloomberg

Bond yields rallied across the yield curve after fear of the outbreak overtook financial markets on January 20th. The 10-year and the 2-year Treasury notes dropped 31 and 24 basis points to 1.51% and 1.32%, respectively, at the end of the month. As of February 12th, these yields retraced roughly halfway back to 1.62% and 1.44%.

Relevant to short-term portfolios is the question of whether the Federal Reserve will cut the fed funds rate in response to market jitters. The Fed has taken such moves to inject market liquidity in the past even in the middle of a tightening cycle. Lower bond yields seem to indicate that the Fed will ease later this year, and as of February 13th, the fed funds futures market (tracked by Bloomberg) is forecasting 1.4 cuts by the end of 2020.

Figure 4: Market Prediction of Fed Funds Moves

Source: Bloomberg

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) concluded its January 28th-29th meeting as expected with no changes to interest rates. In response to a question on how the Fed will respond to the outbreak in China, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell noted that the situation was in its early stages and the Fed was carefully monitoring developments. He ended his answer with “uncertainties about the outlook remain, including those posed by the new coronavirus.”

At his October 2019 press conference Chair Powell remarked that, should “developments emerge that cause a material reassessment” of its outlook on the economy, the Committee will respond accordingly. The Fed’s semi-annual report released on February 7 noted that “the effects of the coronavirus in China have presented a new risk to the outlook3.” This statement may indicate the Fed’s intention to reassess interest rate decisions.

The People’s Bank of China cut borrowing rates on 7-day and 14-day reverse repos and promised to inject 1.2 trillion yuan ($174 billion) as liquidity measures. It is also expected to cut its policy interest if the economic situation worsens in the coming weeks. Elsewhere, major central banks, including the European Central Bank, Bank of England and Bank of Japan, are also on easing paths to combat sluggish domestic growth.

Liquidity investors saw lower yields coming in 2020 due to slower growth prospects and the new outbreak may cause yields to go lower for longer as the Fed cut rates further. Investors may consider moderate duration extension to cushion the expected drop in future portfolio yield.

Earnings Impact and Credit Deterioration

The third factor to consider is how the outbreak may impact portfolio credit quality from a lower volume of sales, higher costs and/or rising debt burden. Firms in different industry groups and sub sectors may be impacted differently. As credit investors, we need not be overly concerned with short-term negative impact to earnings, although short-term effects may linger and become long-term concerns to affect firms’ liquidity and capital positions.

Portfolio composition of a typical high-grade liquidity portfolio provides some credit protection to a regionally contained virus outbreak. Cash investments tend to be limited to US government and agency securities, high-grade financial institutions in North America and Europe and limited non-financial corporate issuers. High minimum credit ratings requirements (generally A or better long-term and Tier -1 short-term) further limit exposure to lower-rated credits in the most impacted sectors.

To assess credit exposure, investors can look at an outbreak’s effect from both the demand and supply sides of the economy. A drop in demand comes from increased public health awareness and reduced public consumption of goods and services. Affected industries and credits may include transportation (including air travel), hospitality, media & entertainment, retail and dining.

An outbreak can affect credits on the supply side through reduced production, transportation restrictions, and disrupted supply chains. Affected credits may come from heavy manufacturing, automotive and other consumer products that rely on imports, oil & gas, power and utilities, base materials and commodities.

For now, we consider the direct credit impact on liquidity portfolios may be limited if the outbreak is contained in China and its neighboring countries. Affected credits may incur revenue losses from reduced demand or supply disruptions but are not likely to experience capital erosion or major credit downgrades. Given the typical concentration in government and financial assets, a liquidity portfolio’s credit risk is further reduced in a portfolio context.

Market Volatility on Portfolio Liquidity

Lastly, one cannot underestimate the impact of an outbreak on financial market liquidity. As with other liquidity events, the fear of an outbreak may have a more powerful impact on liquidity than the outbreak itself. As public confidence in the authorities’ ability to contain an outbreak waxes and wanes, financial markets respond with buying and selling risk-free Treasury securities in strategies known as risk-off and risk-on trades. When the market is in a risk-off mode, there is less interest in buying lower-quality, lesser known names. Investors also tend to shy away from credits perceived to be exposed to the outbreak or those that lack transparency in exposure.

Compared with the safety and yield objectives, the liquidity mandate of a cash portfolio should be more of a priority, as the account may be called upon to provide cash with a short notice. The traditional measure of market liquidity is the ability to exchange a sizable amount of a security into cash very quickly without causing the price to deviate from the quoted price before the trade. Since most short-term investments are held until maturity and not sold in the secondary market, real liquidity characteristics are difficult to observe. In general, securities with high credit ratings, good name recognition and larger offering sizes tend to be more liquid.

Understanding the liquidity impact of an outbreak has been complicated by the low yield environment, compressed yield spreads of different investments, and the distortion created by the Federal Reserve’s temporary open market repo operations. While we don’t anticipate liquidity shortage from the outbreak on the same order of past market crises, this is nonetheless one of the areas to monitor for signs of trouble.

Conclusion: Improve Portfolio Readiness to Cope with Uncertainty

Although confirmed cases and deaths continue to rise in China, US and WHO authorities continue to believe the risk of the outbreak developing into a pandemic is low. As such, the consensus market view is that it will have a moderate and temporary economic impact on the rest of the world economy.

As we digest incoming news flow, we advise our readers to consider the outbreak’s potential impact on their liquidity portfolios with respect to their safety, liquidity and yield objectives. Investors can approach the subject from macroeconomic, interest rates, credit and market liquidity angles. They should determine whether the impact will be temporary or long-lasting, localized to Asia or affecting the global economy.

We think the 2002-2003 SARS epidemic may not be comparable to the current outbreak since China represents a far larger presence in the world economy. Ultimately, the economic impact from a difficult-to-contain virus may not be as much from its direct impact as from the fear that leads to reduced demand, delayed supply and high financial market volatility. Reducing exposure to directly exposed credits may be one solution; improving portfolio liquidity by focusing on strong, well-known credits also helps. When interest rates are expected to stay low, or move lower, investors may consider locking in current yield levels by extending their portfolio duration moderately.

On the other hand, this is not the time for complacency. Strong rallies in the equity market since the end of January seem to display too much optimism. New cases of infection continue to climb at alarming rates, both inside China and elsewhere. Much about the virus and how it is transmitted remains unknown or poorly understood. The efficacy of several drugs in development are at least a few months away and and the timeline for an effective vaccine is even longer. Most people outside the region are relatively relaxed and may not be well prepared for outbreaks in their communities. Therefore, while panic is not the solution, the right amount of vigilance to the potential “tail risks” is warranted.

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

1Mike Bird, Coronavirus Quarantine Will Ripple Through Global Manufacturing, The Wall Street Journal: Markets | Heard on the Street, January 31, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/coronavirus-quarantine-will-ripple-through-global-manufacturing-11580458591

2James T. Areddy, Coronavirus Closes China to the World, Straining Global Economy, The Wall Street Journal, February 3, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/coronavirus-closes-china-to-the-world-straining-global-economy-11580689793?mod=djemalertNEWS

3Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Monetary Policy Report – February 2020. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/2020-02-mpr-summary.htm

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.