Three and Done? Implications for Institutional Cash Portfolios

Abstract

The pause by the Fed after three rate cuts removes some near-term uncertainty for short-term interest rates. On balance, we think the economy faces more headwinds than tailwinds, and thus the probability of further cuts is significant enough to warrant some portfolio readjustment. A yield curve that is no longer inverted provides incentive to invest further out. Growing credit risks in the low rate environment argues for more selective credit decisions.

Introduction

The Federal Reserve concluded its two-day Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting on October 30th with a 25-basis point (bp) cut to the federal funds rate, the third consecutive rate cut since July. The widely anticipated move concluded the central bank’s preemptive move against economic headwinds. Although interest rate futures continue to bet on one more rate cut in 2020, Fed officials appear to be comfortable with holding rates steady for the foreseeable future.

These past few months have been difficult for institutional liquidity investors. After several years of near zero investment returns, investors finally enjoyed meaningful yield in their short-term portfolios as the Fed started raising rates in December 2015. Earlier this year, concerns of a slowing economy led to an inverted yield curve, followed by Fed rate cuts. The yield spread between the 3-month Treasury bill and the 2-year Treasury note was as wide as -51 bps (see Figure 1). As portfolio yield trended downward, investors had to justify the validity of owning longer-term securities at lower yield levels. There was also the possibility that the rate cuts may be not only “an insurance policy” but rather a race to the bottom or even to negative rates.

Figure 1: Yield Spread Between the 2-year and 3-month Treasury Securities

Source: Bloomberg

Since the October 30th FOMC decision, many Fed officials, including Chair Jerome Powell, Vice Chair Richard Clarida, and Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashikari1, one of the more dovish officials on the FOMC, have said that the central bank would likely neither raise nor lower rates for some time. As the Fed pauses, it is a good time for institutional liquidity investors to also pause and reconsider portfolio decisions. How can one take advantage of this pause and realize additional yield without undue sacrifice in credit and liquidity risk?

How the Fed Got to the Point of Holding Steady

Recall that the Fed entered 2019 with a tightening bias on the fed funds rate. The median assessment among Fed officials was for at least two more hikes to take rates from a range of 2.25-2.50% to 2.75-3.00%. Economic slowdowns in the rest of the world, uncertainties from escalating trade tensions and stubbornly low inflation prompted the Fed to reverse direction.

Responding to market anticipation, Chair Powell acknowledged in a June 4th speech that the Fed was open to cutting rates to keep the economic expansion on track2. At that time, the US was threatening to close its southern border with Mexico, President Trump and China’s president Xi Jinping were non-committal about a summit meeting to resolve disputes. Days later, British Prime Minister Theresa May stepped down after failing to rectify a Brexit deal through Parliament.

The market’s focus was either one or two 25 bp rate reductions to insure against negative shocks in the system. In fact, the June FOMC minutes showed Fed officials thought a preemptive rate cut would be warranted to counter “intensified” “risks and uncertainties surrounding the economic outlook3.” The July 30-31 meeting delivered this cut, characterized by Chair Powell as “a midcycle adjustment to policy.”

The three cuts since July were not without disagreements. At the July meeting, two regional Fed presidents voted against the easing decision. At the September meeting, the same two officials dissented, while a third regional Fed president dissented in the opposite direction, arguing for a more aggressive 50 bps cut. The division amongst Fed members reflected disagreements in the wider financial community about the need for “preemptive” rate cuts when the economy was humming at a healthy pace, supported by full employment and strong consumer spending, while dark clouds of a contracting manufacturing sector and lower business spending gathered in the distance.

It is reassuring to know that, after the October meeting, most decision makers at the Fed seem to agree that it has done enough to help the economy stay on the right course. The strong October employment report, which showed an addition of 128,000 new jobs, released several days later seem to confirm this sanguine outlook on the economy.

Three and Done? Historical Experiences

Even before the July decision, some market observers equated these forthcoming rate cuts to the central bank’s moves in the 1990s as “an insurance policy.” Under then Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, the Fed conducted rate hikes to engineer a “soft landing” of the economy in 1994-1995. Fearing that the economy might be slowing too much, officials cut rates in July 1995 and again in December 1995 and January 1996. The comparison is relevant to the current situation as recession risk was low, stocks were rallying, inflation was contained, and the incumbent presidents faced reelections in both periods4.

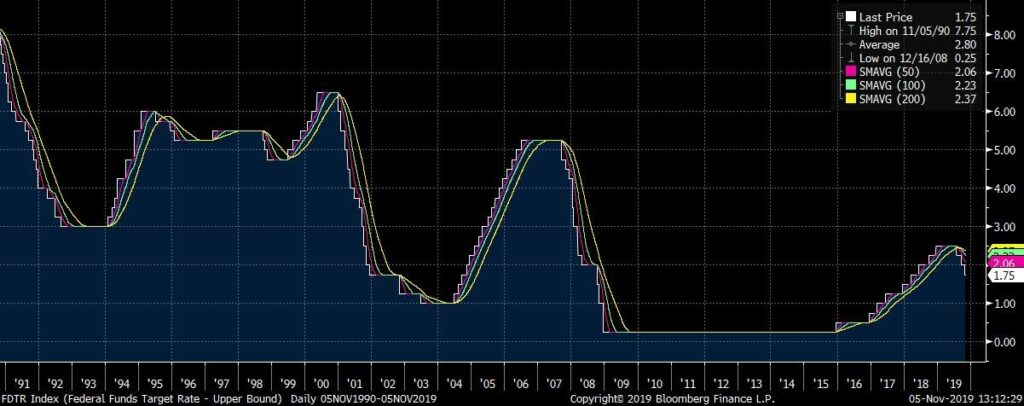

The Fed took out the insurance policy again in 1998 when financial market stability was threatened by the Russian debt default. The Fed cut rates three times in quick succession between September and November. As the Fed did not cut rates to manage a market crisis this time, economists see the 1998 case as less relevant5 (see Figure 2).

The takeaways from these historical insurance cuts are that the Fed appeared to have succeeded in sustaining growth in both cases. It subsequently took the fed funds rate higher after the pertinent issues were dealt with.

Figure 2: Historical Instances of “Insurance” Cuts

Source: Bloomberg

Mission Accomplished?

Chair Powell noted in his prepared remarks at the July post-FOMC conference that the action was to insure against and offset the negative effects of weak global growth and trade policy uncertainty, and to nudge inflation to the Fed’s symmetric 2% target6. The October FOMC statement referred to strong jobs and consumer spending data, weak business fixed investment and exports and inflation running below 2% and no mention of global growth and trade policy. So, did the three cuts accomplish what the Fed set out to do in July? What gave the central bank comfort to move to a holding pattern?

A trade deal remains elusive: The meeting between Trump and Xi in Osaka, Japan last June did not produce a trade resolution. Instead, the US imposed 15% tariffs on an additional $111 billion of Chinese imports, beyond the $250 billion subject to the 25% tariffs which are set to increase to 30% shortly. China responded with smaller tariff increases. In recent weeks, the two sides toned down their aggressive postures, hoping to strike a scaled-back “phase one” deal in November. If phase one becomes a reality, neither the administration nor the market expects a next-phase deal before the 2020 presidential election. Meanwhile, auto related tariffs of 5-15% are scheduled to go into effect in November with European, Japanese and Korean automakers.

Global growth continues to be unimpressive: China’s economy, one of the key growth engines globally, grew at the slowest rate since the 1990s in the latest quarter due to a host of factors. Quarterly GDP slowed from 6.4% in the first quarter to 6.2% and 6.0% in the second and third quarters, still within the government’s target range of 6.0-6.5%. Growth in the eurozone in the second quarter fell to 0.2%, half of the first quarter’s pace, reflecting the region’s decelerating inflation and a manufacturing slowdown in Germany, which caused the country’s GDP to shrink by 0.1%. The UK’s GDP fell 0.2% in the second quarter and continues to face Brexit uncertainty, as the country is headed to a December general election to determine a path forward.

US Inflation runs consistently below 2%: The September US Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) Index came in at 1.3% with the reading at 1.7%, below the Fed’s 2% target. After topping 2% briefly in 2018, this key inflation gauge tracked by the Fed has been below 2% all through 2019 (see Figure 3). Another popular inflation indicator, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) was 1.7% in September, the same level as in August.

Figure 3: US Core PCE Index as of September 2019

Source: Bloomberg

In summary, the headwinds described by Chair Powell in July as reasons for the Fed’s preemptive moves do not seem to have changed materially in the following months. This, of course, does not mean the cuts did not achieve the effect of preventing the economy from losing its growth momentum. Furthermore, it may take several more months for the cuts to work their way through the system. Thus, the verdict remains undecided.

Parsing the Fed’s Next Move

The October FOMC statement indicates that despite weak fixed investments and exports, the Fed sees a healthy jobs market and household spending as clear signs of a strong economy without the need of extra help from monetary policy for now, although it also acknowledges an uncertain outlook to this baseline assumption.

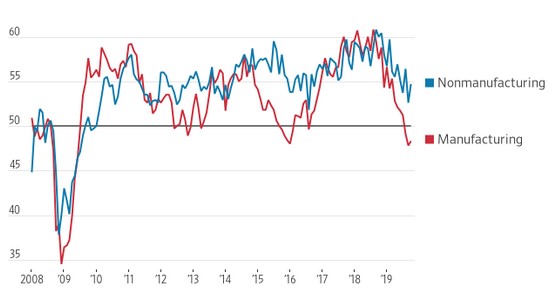

Higher rates not immediately in the cards: Taking stock of the slowing global economy and the late stage of growth in the US, a long path towards trade resolution, contraction in the manufacturing sectors (see Figure 4), waning effects of the 2017 tax cuts, and the Fed’s more patient and “symmetrical” view on the 2% inflation target, we are doubtful of an impending tightening cycle in the next 12 months. Election-year politics also may discourage monetary policy moves that are construed to be helping or hurting the incumbent administration.

Figure 4: Institute of Supply Management Surveys

Source: The Wall Street Journal

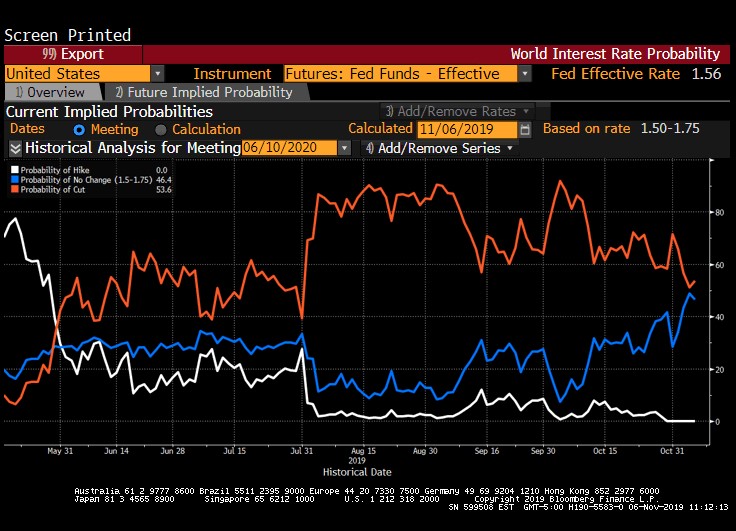

Lower rates delayed but not totally denied: We think that there is more risk for rates to be headed down than up over the same period. The efficacy from the insurance cuts lacks empirical evidence, so it is possible that the Fed will finish the task it started should the economy start to lose momentum again. While mainstream economists and strategists continue to assign a low probability of a recession by 2020, the risk has risen appreciably since the start of the trade war. Throwing in event risks like a presidential impeachment, possible government shutdowns or re-escalation of trade wars, the possibility of lower rates becomes more credible. The interest rate futures market is placing 50% odds of one more cut by the middle of next year (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Futures Market Estimates of the Fed Funds Rate by June 30, 2020

Source: Bloomberg

Portfolio Implications and Strategies

We view the Fed’s decision to hold short-term rates steady as a positive move for liquidity investors because it removed some near-term uncertainty and limited further erosion of income potential.

A curve no longer inverted: After more than six months of sporadic curve inversion, as represented by the yield spread between the 2-year Treasury note and the 3-month Treasury bill, the yield curve is finally upwardly sloping, albeit at a very flat angle (See Figure 1). At a minimum, this positive relationship removes the psychological hindrance of investing in securities out on the yield curve for a lower yield potential.

Take advantage of the respite to reinvest: As we believe that the economy will likely face more headwinds than tailwinds even after trade disputes are settled, we lean in the direction of expecting lower rates rather than higher rates over the next 12 months. As we often advise our readers, trying to pinpoint the timing of the Fed’s next move is a fool’s errand; liquidity portfolios should consider laddering investments out on the yield curve as a preferred strategy. If the Fed stands pat during the holding period, investors still may be rewarded with positive yield pickup.

Stay vigilant on credit risk in a low yield environment: Lower costs of funding often encourage reckless risk taking. A Fed easing cycle often obscures borrowers’ difficulty in funding operations through excessive debt. Now that the Fed has paused, more credit issues associated with lower-rated names may surface, which may in turn affect investors’ perception of overall market risk. Compressed yield spreads between different classes of debt also blur the line of relative creditworthiness among issuers. We urge liquidity investors to be more selective on borderline credits, such as Tier 2 commercial paper debt.

Conclusion – Use the Pause to Reassess Portfolio Strategies

We view the Fed stance after three rate cuts favorably as it removes some near-term uncertainty in the direction and trajectory of short-term interest rates. Despite the central bank’s assurance, we think the economy faces more headwinds than tailwinds to sustain growth at a healthy pace. While not anticipating the Fed to resume a tightening cycle in the foreseeable future, we think the probability of further cuts is significant enough to warrant some portfolio readjustment. A yield curve no longer inverted provides more incentive to reinvest longer. Growing credit risks in the low rate environment argue for more selective credit decisions. As the Fed continues to be active in the repo market to manage daily liquidity, we are reminded that liquidity management from diversified sources remains the top priority for institutional cash investors.

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

1Rich Miller and Christopher Condon, Economics: Powell Signals Fed Policy on Hold Amid Hopes Economy Set for Soft Landing, Bloomberg, October 30, 20190. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-30/powell-signals-fed-policy-on-hold-as-economy-eyes-soft-landing. Howard Schneider, Clarida Says U.S. economy, Fed policy “in a good place”, Reuters, November 1, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-fed-clarida/clarida-says-u-s-economy-fed-policy-in-a-good-place-idUSKBN1XB4Q2; Jeff Cox, Fed’s Kashikari calls for no more rate hikes until inflation hits 2%, CNBC, Updated November 4, 2019. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/04/feds-kashkari-calls-for-no-more-rate-hikes-until-inflation-hits-2percent.html

2Mattew Boesler and Christopher Condon, Economics: Powell Signals Openness to Fed Cut if Needed over Trade Tensions, Bloomberg. Updated June 4th, 2019. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-04/powell-signals-openness-to-cut-rates-if-needed-on-trade-tension

3Refer to the June 18-19, 2019 FOMC minutes at https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20190619.htm

4Nick Timiraos, Economy | The Outlook: Case for Cutting Rates Can Be Found in Close Calls of the 1990s, The Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/case-for-cutting-rates-can-be-found-in-close-calls-of-the-1990s-11560715200

5Rich Miller, Economics: Fed May See 1995-96 Interest Rate cuts as Template for Today, Bloomberg, Updated on April 29, 2019. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-04-28/fed-may-end-up-seeing-1995-96-rate-cuts-as-a-template-for-today

6Read the transcript of Chair Powell’s July 31 press conference here. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcpresconf20190731.htm

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.