Demystifying ESG Investing

Abstract

The popularity of responsible investing has extended to the fixed income and liquidity management fields in recent years. Incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues in cash investment decisions makes sense as part of overall credit risk management. In addition to challenges related to disclosure, criteria, measure and verification, liquidity portfolios face unique challenges in the areas of relevance, concentration, short-termism, and transparency. Rather than buying into a strategy with an ESG label, investors should engage their managers to include ESG issues in general credit evaluation and monitoring to improve risk management.

Introduction

Responsible investing gained popularity with equity investors decades ago and has slowly made its way into the fixed income world, becoming a source of interest among institutional liquidity investors in the past several years. At least two institutional money market funds (MMFs) of this genre launched in the last year, and more may be coming. Separate account managers also receive more inquiries on incorporating responsible investing into a cash portfolio.

Given the vast scope of the subject, this research commentary will provide a primer on the discipline of ESG investing, what it represents, selection criteria and applications. We will end with a brief discussion on the challenges and considerations of ESG issues for institutional cash portfolios.

Definitions

ESG stands for Environment, Social and Governance, the three central factors in measuring the sustainability and ethical impact of an investment1. The term first appeared in a major 2004 study co-sponsored by the United Nations on integrating ESG issues in asset management, securities brokerage services and related research functions2,3.

Besides ESG, several other terms are also widely known in the investment community. They include socially responsible Investing (SRI), sustainable investing, impact investing, and sustainable, responsible and impact investing (also sometimes referred to as SRI—confusing, isn’t it?). Aspects of these disciplines overlap, and financial literature often uses them interchangeably, but each term has a different connotation. We offer a simplified summary below . For the purpose of this primer, we place all under the umbrella term ESG.

- SRI: Socially responsible investing generally focuses on actively excluding investments based on ethical guideline such as weaponry and “sin” stocks. Stated differently, SRI focuses on screening out the “negative” candidates to influence industry/management behavior.

- Impact Investing: This approach selects candidates with positive potential impact based on a set of objectives. Profit potential is a secondary consideration. It focuses on screening in the “positive” candidates.

- ESG: The approach is based on the philosophy that ESG issues are relevant risk factors in the holistic analysis of investment candidates. Candidates with better management of ESG risks can bring better long-term risk-adjusted financial rewards to investors.

A Brief History

The tradition of responsible/ethical investing dates back many centuries. In Biblical times, the Jewish law mandated ethical investing (Leviticus 19:13). SRI began in the US in the 18th century as Methodists, and later Quakers, devised guidelines for the types of companies to avoid, such as those promoting liquor and tobacco products, gambling, and the slave trade5.

SRI became more formalized in the 1960s when the mutual fund industry grew and expanded into wider use. SRI also grew in popularity among Vietnam War protestors in the 1960s. The Community Reinvestment Act in 1977 forbade discriminatory lending in low-income neighborhoods, and in the 1980’s, nuclear fallouts from the Chernobyl and Three Mile Island accidents further spawned anxiety over environmental and climate concerns. Student sit-ins at American universities to end South Africa’s apartheid led to $625 billion of endowment investments redirected from that country by 19936.

The 2004 UN-sponsored ESG study eventually led to $70 trillion in assets from 1,700 signatories aligned with the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) by 20177. The global financial crisis in 2008 also provided a stark reminder of the side effects of pure profit-driven motives in the capital markets. The US Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment’s (US SIF) 2018 annual report puts total SRI investments in the US at $12 trillion, or one of every four dollars of professionally managed money8.

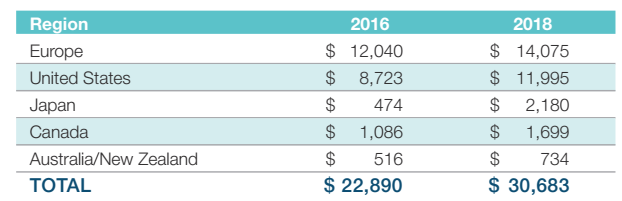

Figure 1: Global Sustainable Investing Assets, 2016-2018

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2018 Global Sustainable Investment Review, page 8, https://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/GSIR_Review2018.3.28.pdf

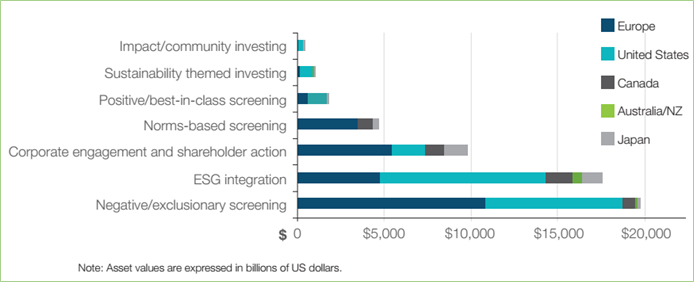

Figure 2: Sustainable Investing by Strategy and Region

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2018 Annual Report, page 10

Disclosure, Criteria, Measurement and Verification Challenges

ESG investing has emerged from the peripheral field of ethical screening to become a core component of long-term risk assessment and stock valuation. With its popularity came ESG ratings services, ESG indexes, and ESG exchange traded funds (ETFs) to help investors measure risks and make decisions.

Several challenges have emerged. On the investments’ side, disclosure is lacking and inconsistent due to a lack of regulatory reporting, standardization, verification and audit requirements. On the investors’ side, the lack of uniform best practices has led to different selection criteria, competing ESG methodologies and the marketing of ESG products with no recognized industry standards.

Disclosure: The UN’s 2004 study called for companies to implement ESG principles and improve reporting and disclosure, for accounting firms to facilitate standardization, for regulators to implement reporting and listing standards, and asset managers to integrate ESG factors into investment processes9. These remain lofty goals today. ESG reporting is far from standardized as many items are non-tangible without quantifiable attributes. Several government functions and organizations are working on common disclosure standards.

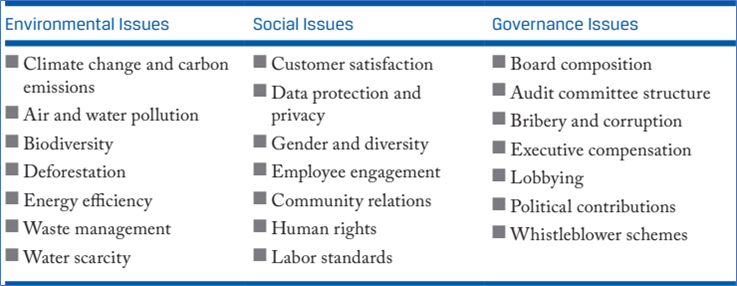

Criteria: The inherent subjectivity of ESG considerations creates competing methodologies for selecting the issues in each of the three areas. Complicating matters further, the criteria also vary from industry to industry. Figure 3 is a sample of ESG issues provided by the CFA Institute10.

Figure 3: CFA Institute’s Examples of ESG Issues

Source: CFA Institute

Measurement: The choice of risk factors and the subjective nature of measurement present challenges to professional asset managers and institutional investors. Some turn to the emerging industry of ESG ratings/rankings service providers such as Reuters, MSCI, Sustainalystics and Morningstar. While these services save time and provide dedicated ESG analysis, they receive their fair share of criticism regarding disclosure limitation, size and geographic bias, inconsistencies across ratings and failure to identify risk. For example, according to analysis by a Washington DC-based think tank, both Volkswagen and Wells Fargo received ESG ratings higher than their peer groups before their respective ESG failures11 were revealed.

Verification: The lack of consistent regulatory and accounting requirements for disclosure means that firms can selectively disclose ESG items favorable to its public relations purposes. Investors’ lack of ability to independently verify ESG disclosures reduces the trustworthiness of such information. The same can be said about the credibility of ESG ratings and fund managers’ proprietary ESG research results when their methodologies remain opaque.

Fixed Income ESG Investing

Historically, ESG focus has been on equity investing and shareholder engagement, however, awareness and initiatives have begun to also shift attention to the world of fixed income. The large size of the debt market relative to the equity market and bond investors’ principal objective of capital preservation make ESG well aligned with fixed income investing.

Substantial debt financing needs by issuers give bond investors a relatively large say on ESG issues, especially for sovereign and municipal issuers without equity market access. There is also growing recognition that ESG issues represent hidden credit risks that could pose material financial impact to bond investors. The debacles of Volkswagen’s emissions scandal and Well Fargo’s fake customer accounts are two such examples. In fact, ESG considerations, even if not identified by name, are already embedded in the credit evaluation process of many professional bond managers.

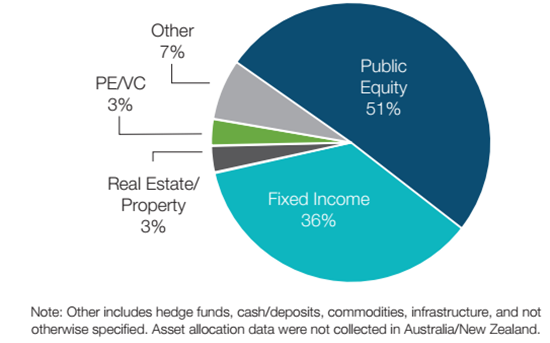

Meanwhile, the markets have seen product innovation, with new bond issuance catering to ESG-minded bond investors. According to the IFC, a subsidiary of the World Bank, annual issuance in the “green bond” market rose from zero to more than $155 billion globally in the decade before 2017 and was expected to reach $200 billion in 201812. The “social bond” market born in 2015 rose quickly to $11.1 billion in issuance by 201813. The UN Global Compact group invites its global partners to raise $3-5 trillion annually, mostly in fixed income, as “mainstream investments” to satisfy the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 agreed to by all 193 UN member states in 201514. As of 2018, 36% of sustainable investing assets are in fixed income, according to Global Sustainable Investment Alliance.

Figure 4: Global Sustainable Investing Asset Allocation 2018

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2018 Annual Report, page 12

MSCI Bloomberg and BlackRock iShares have developed fixed income ESG indices for ETF and other investments. Others are expected to enter the space soon.

Growing ESG Interest Among Institutional Liquidity Investors

In the last three to five years, we have started to receive inquires on ESG investing from institutional cash accounts. This interest makes sense, as many of the same organizations may have adopted ESG emphasis in their retirement or endowment programs. Many treasury practitioners are of the millennial generation who may be more cognizant of the social and environmental impact from financial decisions than previous generations. The long shadow that the 2008 financial crisis cast on our profession also serves as a reminder of grave market consequences from failure in corporate governance.

Service providers have taken notice of the trend. The launch of the DWS ESG Liquidity Fund (ESGXX), an institutional money market fund, in October 2018 kickstarted the race to bring ESG investing to the institutional liquidity world. In April 2019, the BlackRock Liquid Environmentally Aware Fund (LEAF), became the first “green” (environmental) MMF in the US. One other fund, the State Street ESG Liquid Reserve Fund, has been filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission in April and other fund managers may follow this trend. There are also ESG-flavored ultra-short duration bond funds catered to liquidity investors.

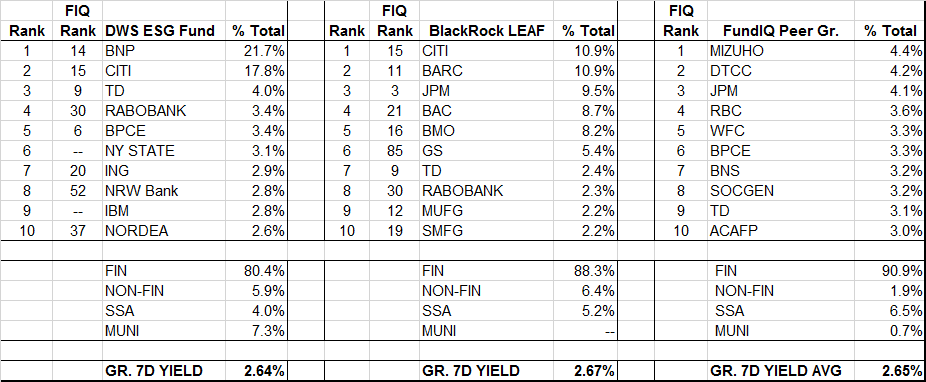

Figure 5: Top 10 Holdings in ESG Funds Compared to the FundIQ® Universe

Source: Fund N-ΜPF filings with the SEC as of April 30, 2019. FundIQ® Peer Group consists of 13 of the largest AAA rated prime institutional MMFs in the US tracked by Capital Advisors Group, Inc.

Practical Challenges for Cash Investors

While the incorporation of ESG factors in institutional cash portfolios sounds exciting and enticing, there are several implications and obstacles that investors should bear in mind. While some of these challenges may be overcome in due course, others involve the optics vs. substance debate. The challenges are further complicated by how investors perceive institutional prime MMFs with their Variable Net Asset Values (NAVs) and emergency liquidity gates and fees.

Relevance: Institutional cash portfolios buy high grade, short-duration investments. Most eligible investments tend to be either government or financial institutions debt. Companies in the “dirtier” non-financial sectors often do not meet minimum credit ratings or yield requirements. While governance and social aspects can be relevant filters, the environmental impact from a green MMF may be less material.

Concentration: Like other prime funds, ESG funds are subject to regulations on issuer concentration. Overlaying ESG filters on top of a stringent approved list from a finite universe of eligible names means increased difficulty in complying with the 5% per issuer concentration limit. This may push a fund to accept a less creditworthy name or increase allocation to government securities, either increasing risk or reducing yield potential.

Short-termism: A recurring theme with ESG issues is that they do not fit well with short-termism in investing, since risk outcome or behavioral impact shows up over a long-term valuation period15. Cash portfolios are short-term by design, thus may derive fewer financial benefits from ESG considerations. This requires Investors to be motivated by “non-financial” objectives and be willing to accept lower return potential.

Transparency: The inconsistencies of ESG disclosure affect all investors. Some popular cash instruments, such as asset-backed commercial paper and municipal revenue bonds, do not provide meaningful disclosure. This lack of transparency extends to portfolio managers who may not adequately share how they screen and apply ESG filters.

Applying ESG to Institutional Cash Portfolios

The development of ESG initiatives in the fixed income world is encouraging and exciting for institutional liquidity investors. There are also risks and obstacles associated with incorporating ESG principles in such portfolios. We are at an early stage of this process, so a prudent approach is warranted. We recommend the following general principles.

Consider ESG in everything, not necessarily just in an ESG fund: ESG issues are hidden risk factors that impact the credit quality of a portfolio. An institutional risk analytical framework should incorporate ESG perspectives as part of fundamental credit research. ESG should be on everyone’s radar screen when considering credit investments. This does not mean one has to be in an ESG fund, as the industry is still developing.

Focus on governance and social aspects: Of the three core areas, disclosure on governance is probably the most developed. It is also more relevant, material and measurable to investors from a financial perspective. Data points on social issues are improving but tend to be qualitative and inconsistent with respect to disclosure. Environmental issues, on the other hand, tend to be less relevant to cash instruments from a practical standpoint.

Active involvement: Currently, it may make sense for institutional investors to engage outside managers to implement ESG strategies in their portfolios. Due to issues discussed above, investors need to take an active role and engage the managers on discussions related to selection criteria, ESG filter application, monitoring and portfolio rebalancing. Such discussions may include topics of whether their ESG interest is values-based or value-based, where they have a strong position, and how they view the opportunity cost in forgoing instruments with higher yield potential but lower ESG score.

Conclusion

Incorporating ESG issues in cash investment decisions is a valid approach. The underlying philosophy has changed from penalizing bad actors and rewarding good corporate behaviors to including ESG issues as relevant credit risk factors with material financial impact. Daunting tasks remain in disclosures, selection criteria, measurement and varication by debt issuers, although initiatives are in place to improve them.

Fixed income portfolios may benefit more than stocks from ESG research. Liquidity portfolios have their own challenges with ESG, mostly due to concentration risk and the short-term nature of cash investments. Rather than buying into a strategy with an ESG label, we encourage investors to engage their managers to include ESG issues in general credit evaluation and monitoring to improve risk management. Unlike comingled funds, the customized nature of separate accounts may allow liquidity accounts to achieve their active ESG objectives without the constraint of issuer concentration and manager selection bias.

DOWNLOAD FULL REPORT

Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use.

1Definition from Wikipedia, accessed on May 31, 219, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmental,_social_and_corporate_governance

2The Global Compact, Who Cares Wins, Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World, https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/events/2004/stocks/who_cares_wins_global_compact_2004.pdf

3Georg Kell, The Remarkable Rise of ESG, Forbes, Jul 11, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgkell/2018/07/11/the-remarkable-rise-of-esg/#e4652216951f

4Michelle Zhou, ESG, SRI & Impact Investing: What’s the Difference? Investopedia, updated May 28, 2019, https://www.investopedia.com/financial-advisor/esg-sri-impact-investing-explaining-difference-clients/

5James Lumberg, A History of Impact Investing, Investopedia, Updated June 22, 2017, https://www.investopedia.com/news/history-impact-investing/

6Schroders, Global Investor Study, A short history of responsible investing, November 28, 216, https://www.schroders.com/en/insights/global-investor-study/a-short-history-of-responsible-investing-300-0001/

7MSCI ESG Research, Bloomberg Barclays MSCI ESG Fixed Income Index Family Primer, September 2017, https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/7944701/Bloomberg+Barclays+MSCI+ESG+FI+Index+Guide.pdf/cce7006e-697e-4ae4-9cee-23462115907e

8US SIF, SRI Basics, What is sustainable, responsible and impact investing? https://www.ussif.org/sribasics

9The Global Compact, Who Cares Wins, page v.

10CFA Institute, Environmental, Social, and Governance Issues in Investing, A Guide for Investment Professionals, 2015, Page 4, https://www.cfainstitute.org/-/media/documents/article/position-paper/esg-issues-in-investing-a-guide-for-investment-professionals.ashx

11Timothy M. Doyle, Ratings That Don’t Rate, American Council for Capital Formation, July 19, 2018, https://accf.org/2018/07/19/ratings-that-dont-rate-the-subjective-world-of-esg-ratings-agencies/

12International Finance Corp, Green Bonds, Perspectives: Capital Markets, Climate Finance, https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/news_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/news+and+events/news/perspectives/perspectives-i1c2

13BloombergNEF, Social Bond Market Tops $11 billion as Financials Wake Up, February 5, 2019, https://about.bnef.com/blog/social-bond-market-tops-11-billion-financials-wake/

14UN Global Compact, SDG Bonds & Corporate Finance, A Roadmap to Mainstream Investments, A White Paper, https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/publications/SDG-Bonds-and-Corporate-Finance.pdf

15CFA Institute, Environmental, Social and Governance, Issues in Investing, page 6

Please click here for disclosure information: Our research is for personal, non-commercial use only. You may not copy, distribute or modify content contained on this Website without prior written authorization from Capital Advisors Group. By viewing this Website and/or downloading its content, you agree to the Terms of Use & Privacy Policy.